Alabama judges stop issuing marriage licenses altogether to avoid gay marriage

Loading...

| MONTGOMERY, Ala.

As Alabama's all-white Legislature tried to preserve racial segregation and worried about the possibility of mixed-race marriages in 1961, lawmakers rewrote state law to make it optional for counties to issue marriage licenses.

Now, some judges who oppose same-sex marriage are using the long-forgotten amendment to get out of the marriage business altogether rather than risk issuing even one wedding license to gays or lesbians. In at least nine of Alabama's 67 counties, judges have quit issuing any marriage licenses since the U.S. Supreme Court legalized same-sex unions in June.

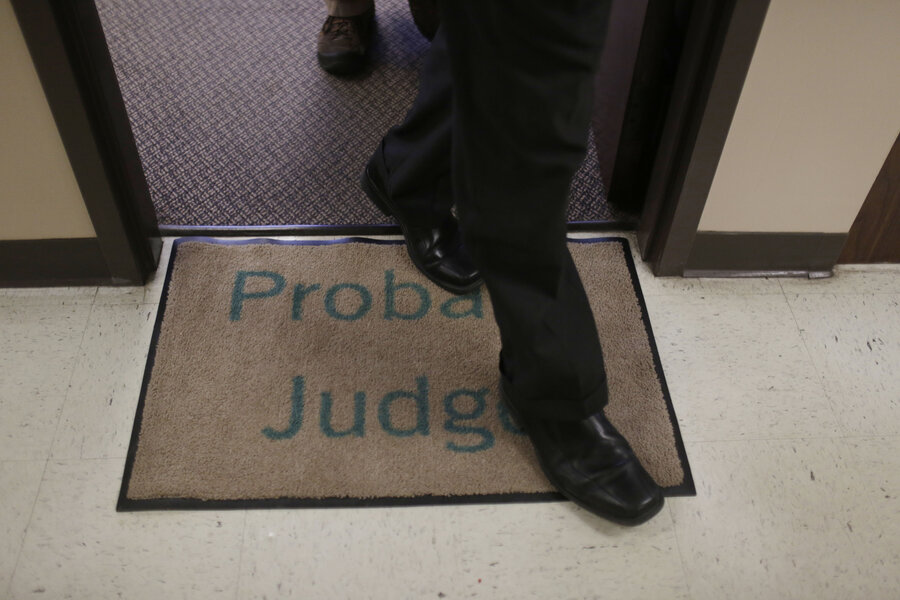

While the precise reason that lawmakers gave for making the 1961 change has been lost to time, the 54-year-old provision says probate courts "may" issue rather than "shall" issue wedding licenses.

Nick Williams, a Baptist minister who also serves as probate judge in Washington County, is among those who have left the marriage license business. He says issuing a license for a same-sex union would violate his Christian beliefs.

"It is a religious freedom issue, but more than that I believe it is a constitutional issue," said Williams, who last month cited the arrest of Kentucky county clerk Kim Davis in asking the Alabama Supreme Court to declare that officials don't have to allow same-sex marriage if doing so violates their religious beliefs.

Like Davis, Williams said he would go to jail before he would approve a marriage license for a gay or lesbian.

Judges in three adjoining counties stopped issuing licenses for similar reasons, creating a region in southwestern Alabama where marriage licenses aren't available for 78,000 people. As a result, Bo Keahey and fiance Hannah Detlefsen will have to spend nearly two hours on the road traveling to and from Monroe County before their November wedding because their native Clarke County has quit issuing licenses.

"I pay taxes here and it's kind of ridiculous that I can't get a license here," said Keahey, an attorney.

Others have encountered similar problems. Daniel Hopkins and Whitley Jones drove 40 miles from their home in Mobile County to buy a marriage license at Williams' office before finding out Washington County no longer issued them.

Frustrated after the refusal, the two had to get back in the car for a 62-mile drive to the probate office in Mobile, which is issuing licenses under order of a federal judge.

The drive might not be needed without that 1961 law.

With then-Gov. John Patterson pushing to maintain segregated public schools and Freedom Riders crisscrossing the South in opposition to segregation, two Alabama legislators, Reps. F LaMont Glass of Greenville and H.B. Taylor of Georgiana, introduced a bill to revamp the state's marriage law in May 1961.

Under a statue that went back decades, couples had to get marriage licenses in the county where the woman lived or where they planned to wed. The law had the effect of requiring each county to issue wedding licenses.

But that changed under Glass and Taylor's bill, according to the Alabama Legislative Reference Service, which researches laws and drafts legislation.

The new law, which records show passed unanimously, included this line: "Marriage licenses may be issued by the judges of probate of the several counties." Since the U.S. Supreme Court's June ruling, some same-sex marriage opponents have used that word "may" to avoid issuing marriage licenses. So far, no one has sued them.

Whatever the stated reason for the 1961 bill, it clearly emerged from a pro-segregation legislature. Alabama's Constitution had included a prohibition on mixed-race marriage since 1901. Not until 2000 did voters overturn the long-invalidated provision.

In the early 1960s, Alabama historian Carl Grafton said, legislators were introducing a "host of bills" to hinder integration.

While Grafton said he wasn't familiar with the '61 marriage law, he added, "It's certainly consistent with the era."

The bill received virtually no news coverage at the time and its sponsors died years ago.

Former Gov. Albert Brewer, who was a young House member in 1961, said neither Glass nor Taylor was known as a hard-core segregationist, and they may have introduced the bill simply as a favor to a judge who didn't want to be bothered by issuing marriage licenses.

Or, Brewer said, it could have been a subtle way to block mixed-race marriages.

"Certainly they were talking about miscegenation at the time," said Brewer, 86.

Whatever the reason for its passage, the law plainly states that judges "may" issue licenses, Williams said.

"There's a big difference between 'may' and 'shall,'" he said.