Trayvon Martin case reveals confusion over how Stand Your Ground works

Loading...

| Atlanta

Stand Your Ground laws were sold in US legislatures primarily as a victims’ rights measure, to limit what many saw as prosecutors second-guessing situations where someone had a split second to make a life-or-death decision to defend themselves with force.

But in the wake of the Trayvon Martin tragedy in Sanford, Fla., as well as the racially charged rampage last week in Tulsa, Okla., some critics are now wondering whether the gutting of prosecutorial discretion in many self-defense cases has created a legal no man’s land.

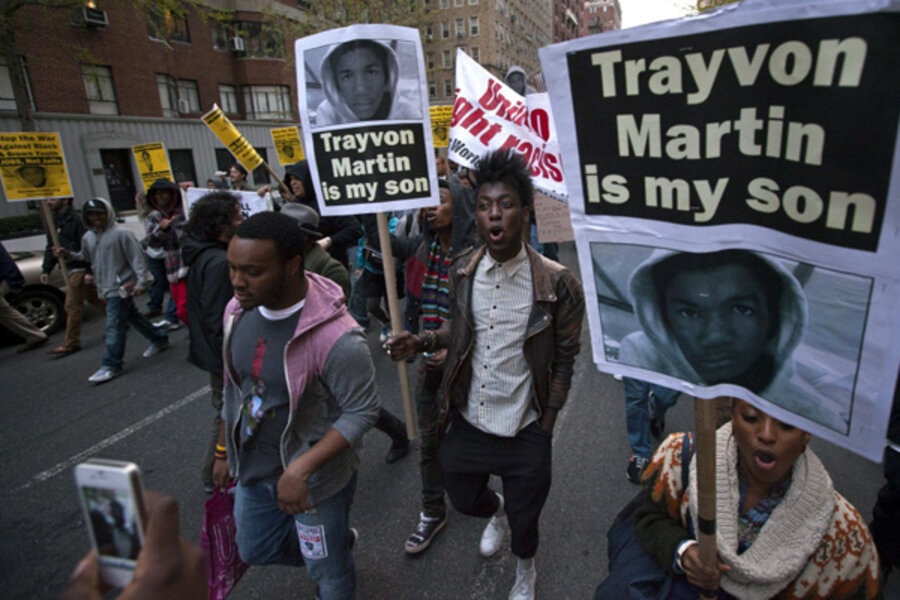

George Zimmerman has claimed self-defense in the fatal shooting of Trayvon, an unarmed teen. Although reports Wednesday indicated that Mr. Zimmerman would be charged, the initial decision by police to not arrest him spurred protests and threats. On Monday, for example, an empty police car was riddled with bullets near the scene of the Feb. 26 shooting.

In the Oklahoma case, part of the motivation for the rampage may have been a police judgment about self-defense in an earlier incident. Oklahoma has had a Stand Your Ground law since 2006. In the shootings last Friday, two white gunmen wounded five random black people, killing three.

The way that Stand Your Ground laws have operated in these cases – particularly the Florida one – has offended many people’s sense of justice. In their eyes, it even signals the changing of a basic social compact, as they wonder whether the government has the tools to properly administer street justice.

At the least, the cases have revealed confusion among both the police and the public over how Stand Your Ground is supposed to work.

“The waters get muddied because a lot of this legislation changes the burden of proof and standard of review,” says Steven Jansen, a spokesman for the Association of Prosecuting Attorneys in Washington, which has opposed tenets of the Stand Your Ground laws. “Before, you would have an objective standard: What would a prudent person have done in a similar situation? And now, it’s more of a subjective test: You have to get inside the mind of the person that has used deadly force.”

Pushed by pro-gun-rights groups like the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the American Legislative Exchange Council, Stand Your Ground laws seem simple on their face. Under such laws, legally carrying citizens have no legal obligation to retreat from a dangerous situation, and they need not fear prosecution if they reasonably meet force with equal or deadlier force to protect themselves or someone else in public.

In the mid-2000s, the US public was ready to listen to that logic, according to a study of the laws by the National District Attorneys Association. Events including 9/11 and hurricane Katrina had shaken Americans’ sense of security, and many felt that the justice system could not adequately protect crime victims.

But as the Trayvon Martin case has taken twists and turns, it’s become clear to many legal experts that the Stand Your Ground concept has many inherent ambiguities, undermining faith in the justice system in the process.

At a legislative task force last week on Stand Your Ground called by Florida state Sen. Chris Smith (D), it was “clear that there was lots of confusion around the statute,” even among seasoned police officers and prosecutors, says Joëlle Anne Moreno, a former federal prosecutor and now a law professor at Florida International University in Miami who is part of the task force.

“The fact is, we haven’t had this law for that long, and we’re still working with it, still trying to figure it out,” she says.

In fact, of the nearly 100 Stand Your Ground defenses in Florida since 2005, the majority were successful – suggesting to police that the benefit of the doubt should primarily go to the person claiming self-defense.

"If police expect and anticipate there might be a Stand Your Ground defense, they're specifically instructed to act with much more deference," says Professor Moreno.

Stand Your Ground legislation also seems to have played a role in the Oklahoma rampage. That became more apparent on Monday, when one of the two suspects, Jake England, admitted that he was in a depressed and vengeful mood in part because of the circumstances of his father’s death in 2010.

Carl England, the alleged shooter’s father, was fatally shot by a black man who had threatened his daughter and tried to kick in the door of her home. That man, Pernell Jefferson, was charged with robbery and weapons offenses, but not with homicide – after police determined he acted in self-defense after being hit with a stick by Mr. England.

“Today is two years that my dad has been gone, shot by a [expletive n-word],” Jake England recently wrote on a social networking website.

In 2009, Florida prosecutors used Stand Your Ground to decide that a homeowner who shot (but did not kill) an unarmed neighbor, Billy Kuch, in his front yard would not be prosecuted, since the homeowner had felt “threatened.”

"I have no problem with people owning guns to protect themselves," Bill Kuch, Billy's father, told the Washington Post. "But somehow, we've reached the point where the shooter's word is the law. The victim doesn't even get his day in court. I don't think most Americans realize it, but that's where we are."

For their part, supporters of Stand Your Ground and other gun laws say many of the reactions to the Trayvon Martin shooting smack of political opportunism.

Officials should not be “stampeded by emotionalism,” Marion Hammer, an NRA lobbyist who helped write Florida’s law, told The Palm Beach Post. “This law is not about one incident. There is absolutely nothing wrong with the law.”

Other supporters of Stand Your Ground zero in on the confusion surrounding the law, which they say has led to misconceptions about the legislation.

“There’s obviously some attempt by gun prohibition lobbies to terrify the public about the Florida law, and which necessarily involve misdescribing them,” says Dave Kopel, research director at the Independence Institute in Golden, Colo. “They try to make it seem like the Florida law is any different from the law in most other American states, or that it’s any different from traditional American law.”

Yet skeptics remain.

The problem is, “you lose faith in the legitimacy of the justice process if you feel cases are unresolved or resolved in a way that suggests a sort of unfair or biased result,” says Moreno, the former federal prosecutor. “At a very sort of basic level, [these laws] change how we view the sanctity of human life. If we’re allowed to shoot somebody for reaching into your car to grab a purse, does it mean that we don’t value human life the way we thought we did?”