Guantánamo: Secret evidence is thorny issue at 9/11 pretrial hearing

Loading...

| Fort Meade, Md.

Accused 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and four alleged co-conspirators were back before a military judge at Guantánamo on Monday as lawyers began a week-long series of hearings to decide unresolved legal issues in advance of the still-unscheduled war crimes trial.

Pending before the court are matters related to the protection of classified information, alleged government invasion of the attorney-client privilege, and the severity of the conditions of the defendants’ pre-trial confinement in a secret wing of the US terror detention facility, among others.

The proceedings were monitored by reporters at Guantánamo and via a live broadcast at Fort Meade in Maryland.

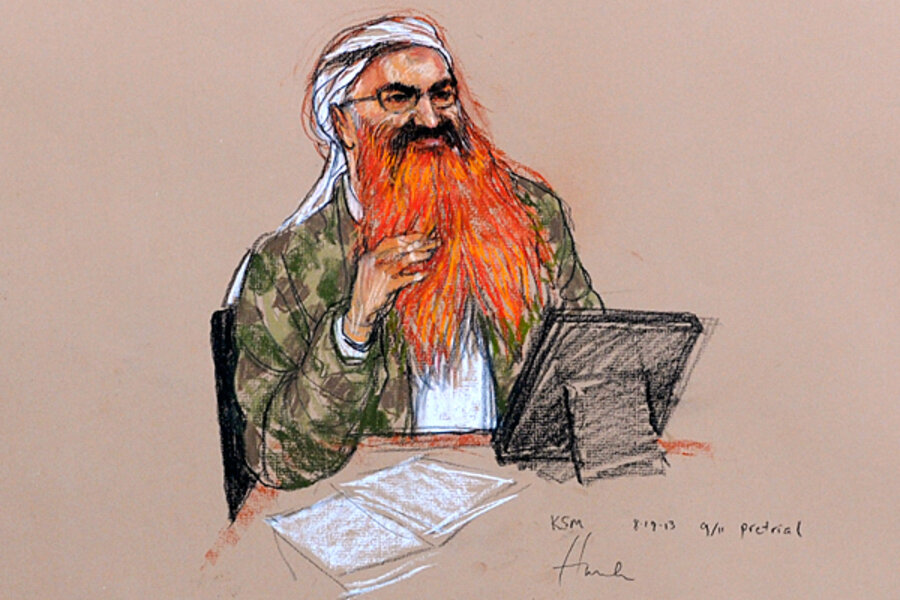

During the hearing, Mr. Mohammed sat at the defense table dressed in a green military-style camouflage jacket and white turban. Much of his lower face was concealed beneath a thick red beard.

He appeared alert and engaged in the proceeding.

The session marked the fifth time lawyers for the five defendants have squared off against military prosecutors since May 2012, when the defendants were formally charged with nearly 3,000 counts of murder and other crimes related to the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks.

The US government is seeking the death penalty for all five defendants.

Much of the legal wrangling is over how to handle classified information.

Although such procedures are well-established in US federal courts, the Obama administration decided to prosecute the men at Guantánamo before a military commission.

The hybrid military tribunal system is specially-designed to offer robust protections of information the government has deemed to be sensitive, while offering fewer legal protections for the accused than they’d receive in the federal court system.

At the hearing, defense lawyers expressed concern about having to agree to accept and examine certain “classified” pieces of evidence that the US government says cannot be shown to the defendants. The lawyers must pledge not to share or discuss the information with their clients.

The judge in the case, US Army Col. James Pohl, approved the government-requested procedure in January. So far only one lawyer has signed the agreement.

Mr. Mohammed’s defense lawyer, David Nevin, told the judge the issue puts him in the difficult position of pitting his client’s ability to view the evidence presented against him against the lawyer’s responsibility to follow the judge’s order establishing a procedure for the trial.

“We cannot explain this to our clients,” said James Harrington, defense lawyer for Ramzi Bin al-Shibh.

He wondered aloud how one tells a defendant in a capital case that the government wants to put you to death but also doesn’t want you to see all the evidence it feels it needs to present to win a conviction. What do you say to a client under those circumstances, he asked, “just trust me and trust that the system is trying to be fair?”

“It highlights the ethical struggle we are dealing with,” Harrington said.

The one lawyer who has signed the agreement is James Connell, counsel for Ali Abdul Aziz Ali. He said he signed the agreement in the hopes of speeding the discovery process. But he quickly added that he has yet to receive any significant government evidence.

Also on Monday, two federal agents testified about their involvement in interrogating Mustafa al-Hawsawi, a co-conspirator who allegedly offered logistics and financial support prior to the 9/11 operation.

Hawsawi’s lawyer, US Navy Cmdr. Walter Ruiz, sought details of the circumstances of his client’s questioning at Guantánamo after years of enduring harsh interrogations in the custody of the Central Intelligence Agency.

The agents, one with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the other a military investigator, were part of a team assembled to collect un-coerced statements from various detainees that could later be admitted as evidence against them at a trial.

Mr. Ruiz asked why the agents conducted the interrogation without the use of a translator. Hawsawi is an Arabic speaker who knows some English.

The questions suggest that Ruiz will attempt later during the trial to undercut the evidentiary value of any statements his client made to the agents by suggesting that he did not fully understand what was being asked.

One of the agents, Steven McClain, a member of a Defense Department counter-terrorism task force, said he did not seek to test Hawsawi’s comprehension of the English language prior to the interrogation.

“Who decided Hawsawi would not use a translator in the interrogation,” Ruiz asked.

“I do not recall,” McClain said. “He was asked if he wanted a translator. He said no.”

McClain said the audio of the interrogations was not recorded. He noted that there were cameras in the interrogation room but he did not know if the sessions were videotaped.

Ruiz asked if Hawsawi was given Miranda warnings or advised of a right to see a lawyer.

“No,” the agent responded.

McClain said the interrogators told Hawsawi that he was free to end the questioning and leave the interrogation room at any time.

“Was he shackled,” Ruiz asked.

A prosecutor objected to the question, saying that issue would be explored in a later hearing.

“Sustained,” the judge declared.

Did Hawsawi appear to understand the questions, Ruiz asked.

McClain said that based on his observations, Hawsawi “fully understood what was happening” in the interrogation room.

Progress during the Monday session came haltingly in large part because of health issues raised by two defendants.

Hawsawi arrived at the hearing wearing a neck brace. Ruiz told the judge that his client had a back condition that made it difficult to sit for long periods of time. After attending a portion of the hearing, Hawsawi told the judge he wanted to return to the camp and voluntarily waived his right to be present at the pre-trial hearing.

Later in the afternoon, a second defendant, Walid Bin Attash, told his lawyer that he was not feeling well. But unlike Hawsawi, Bin Attash was unwilling to waive his right to be present at the hearing.

Judge Pohl questioned a physician who had examined Bin Attash about a stomach condition. The doctor said the condition was painful and that Bin Attash had been receiving medical treatment for the condition for 10 days.

The judge recessed the hearing about an hour early. It is unclear whether Bin Attash will feel well enough to attend Tuesday’s scheduled hearing.