US Supreme Court deals blow to death penalty in Florida case

Loading...

The United States Supreme Court on Tuesday struck down as unconstitutional the procedure used by Florida judges to sentence defendants to death.

The action is expected to make it more difficult to issue death sentences in Florida by requiring the direct involvement of a jury in the decision to end a convicted defendant’s life.

Death penalty opponents hailed the decision as progress toward abolition of capital punishment in the US. It comes at a time of heightened concern nationwide about the fairness of the death penalty and at a time of increased scrutiny of capital punishment cases.

“By striking down Florida’s capital punishment scheme, the Supreme Court restored the central role of the jury in imposing the death penalty,” Cassandra Stubbs, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Capital Punishment Project, said in a statement.

“Juries across the country have become increasingly reluctant to vote in favor of death,” she said. “The court’s ruling thus represents another step on the inevitable road toward ending the death penalty.”

The high court ruled 8 to 1 that Florida’s capital sentencing scheme did not comply with constitutional safeguards because it authorized Florida judges rather than juries to issue death sentences.

“We hold this sentencing scheme unconstitutional,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the majority opinion. “The Sixth Amendment requires a jury, not a judge, to find each fact necessary to impose a sentence of death.”

Under Florida’s approach, a jury is required at trial to determine whether the defendant is guilty of a capital crime. After a conviction, the jury moves to the sentencing phase of the trial.

In the sentencing phase, the jury is required to weigh any aggravating and any mitigating circumstances that might support or undercut a death sentence. The jury is then required to issue an advisory sentence.

Once that advisory sentence has been issued, Florida law requires the trial judge to give “great weight” to the jury’s recommendation. But ultimately the judge’s sentencing order must reflect the judge’s independent judgment about the aggravating and mitigating factors, according to Florida law.

Without such judge-made findings, the maximum punishment someone convicted of a capital crime can receive in Florida is life in prison without parole.

The Supreme Court said the flaw in Florida’s capital sentencing system was that it relied on the judge rather than the jury to make the final determination that the defendant would be sentenced to death.

The Supreme Court had twice upheld the Florida capital sentencing scheme in 1984 and in 1989. But Justice Sotomayor said those earlier decisions had been undercut by a 2002 Supreme Court decision in an Arizona death penalty case.

“Time and subsequent cases have washed away the logic of” the earlier decisions, she wrote.

The capital sentencing scheme in Florida is a hybrid among states that enforce capital punishment. In addition to Florida, Alabama and Delaware authorize advisory sentences from juries in death cases with a judge making the final determination of life or death.

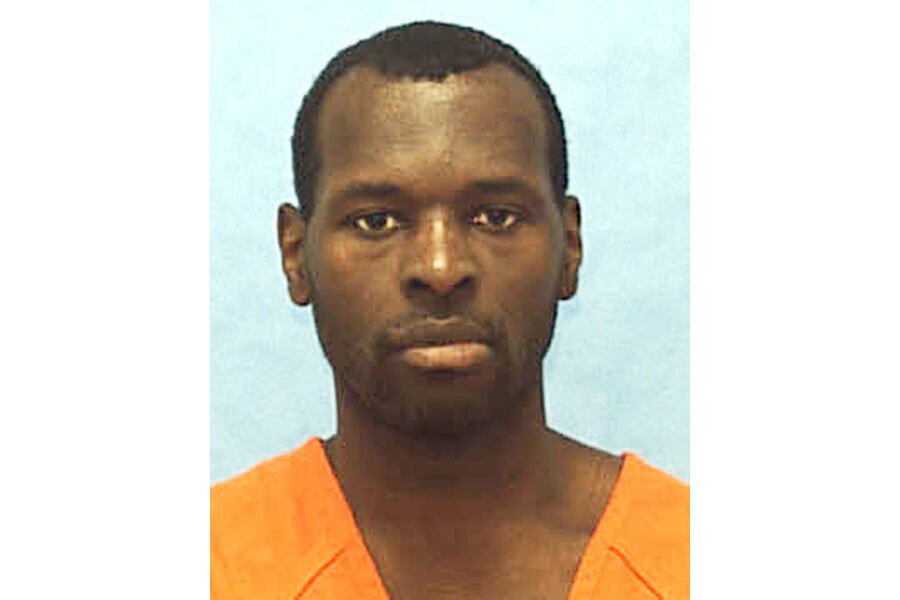

The high court decision came in the case of Timothy Lee Hurst, who was convicted of the 1998 murder of an assistant manager at a Popeye’s Fried Chicken restaurant in Escambia County. Mr. Hurst was a Popeye’s employee. He and the assistant manager were the only two employees scheduled to work at the time the assistant manager was killed in gruesome fashion.

Hurst told two friends that he killed the manager and robbed the store, according to court files. He asked one of the friends to hide a container of money that he said was from the Popeye’s safe. He also asked his friend to wash his bloody clothes, according to court files.

When questioned by police, Hurst said he had not gone to work at Popeye’s that morning and had nothing to do with the killing.

Hurst was convicted in 2000 and the jury voted 11 to 1 to recommend a death sentence. The trial judge imposed a death sentence. (Although the jury must vote unanimously to return a conviction, a Florida jury can recommend a death sentence by majority vote.)

On appeal, Hurst argued that he had a mental disability and was thus not eligible for a death sentence. He was granted a new sentencing hearing in 2012.

After that hearing, the jury voted 7 to 5 to recommend a death sentence. After concluding that Hurst was not mentally disabled and that aggravating circumstances outweighed any mitigating factors, the trial judge imposed a sentence of death. The sentence was upheld by the Florida Supreme Court.

In reversing and remanding that decision, Sotomayor said the jury’s role in capital sentencing is crucial.

“The Sixth Amendment protects a defendant’s right to an impartial jury,” she wrote. “This right required Florida to base Timothy Hurst’s death sentence on a jury’s verdict, not a judge’s factfinding. Florida’s sentencing scheme, which required the judge alone to find the existence of an aggravating circumstance, is therefore unconstitutional.”

In a dissent, Justice Samuel Alito said the Florida jury in the Hurst case played a significant role in determining factors necessary to justify a death sentence. In contrast, he said, the Arizona jury in the 2002 case cited by the majority justices played no role in the capital sentencing process.

“Under the Florida system, the jury plays a critically important role,” he said.

Justice Alito added that even if there was a constitutional violation in the procedure used to sentence Hurst to death, that error did not influence the outcome of the case.

The evidence against Hurst is “overwhelming,” Alito said. “In light of this evidence, it defies belief to suggest that the jury would not have found the existence of either aggravating factor if its finding was binding.”

Sotomayor said in the majority opinion that the high court would leave it to the state courts in Florida to decide whether the error was harmless.

Howard Simon, executive director of the ACLU of Florida, praised the high court’s decision. He said the Florida legislature had been urged repeatedly to shore up Florida’s capital punishment sentencing scheme to enhance the jury’s role.

“Florida leads the nation in the number of people exonerated or released from death row for any reason,” he said in a statement. “Florida is also the only state that allows a jury to recommend a death sentence by a majority vote,” he added. “There is a relationship between these two aspects of the death penalty system in Florida.”

The case was Hurst v. Florida (14-7505).