Former Democratic Party chairman Robert S. Strauss dies

Loading...

| Washington

Dealmaker and political powerbroker Robert S. Strauss, a former Democratic Party chairman whose counsel also was prized by Republicans, died Wednesday. He was 95.

A spokesman for Strauss' law firm, Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld, confirmed the death but released no other information.

Strauss, a quick-witted and gregarious Washington insider with a soft Texas drawl, moved easily in the city's political, business and social circles. Mixing outlandish boasts with a self-deprecating humor, he regularly told listeners: "It ain't braggin' if you've done it."

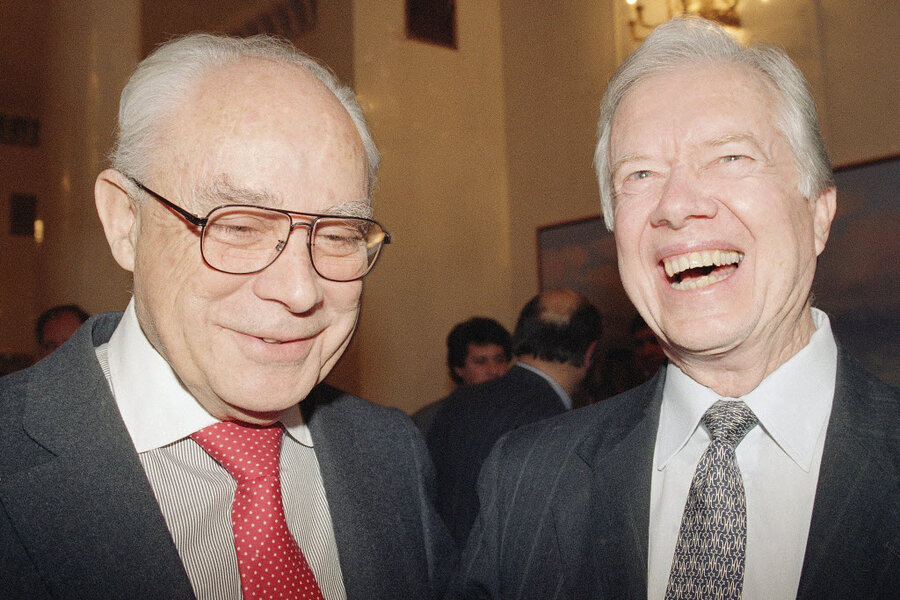

An intimate and political ally of President Jimmy Carter — he managed Carter's two presidential campaigns — Strauss later advised Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. At a time of upheaval in the Soviet Union, Bush sent the politically surefooted Texan to Moscow as U.S. ambassador.

In a statement Wednesday, Bush said that Strauss' "lifelong devotion to the Democratic Party never precluded his ability to work across the aisle on matters of national importance. ... He counseled several presidents of the United States of both parties — and like the others, I valued his advice highly."

When Strauss' appointment to represent the U.S. in the Soviet Union was criticized on grounds that he lacked the geopolitical background required for such a sensitive posting, he said: "While I'm no expert on these things, I'm an expert on people."

Testifying at his Senate nomination hearing in 1991, Strauss pledged a strong voice in dealing with the Soviets. "I may not convince everyone. But they will know where we stand."

During his 15-month tenure as ambassador, Strauss witnessed the fall of Mikhail Gorbachev's communist government and the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Strauss relinquished his ambassadorial post to return to the powerhouse law firm he co-founded in 1945 in Dallas. He never established the type of relationship with President Bill Clinton that he enjoyed with previous presidents, attributing the distance from his fellow Democrat to a difference in age.

More recently, Strauss was a superdelegate during the 2008 presidential campaign. He remained neutral during the long battle between Sens. Barack Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton. In a May 2008 essay in The Washington Post, he said each one had "waged brilliant campaigns. ... America would be in good hands if either became president."

The University of Texas' school of international security and law in Austin bears Strauss' name. He also has held the Lloyd Bentsen chair at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at UT.

Strauss was born on Oct. 19, 1918, in Lockhart, Texas. He grew up in Stamford, where his father was a dry goods merchant. His parents were Jewish, but he received no formal religious instruction.

He first dipped into politics while a student at the University of Texas, when he worked on Lyndon B. Johnson's first congressional campaign. After earning his law degree in 1941, he joined the FBI, where he spent the war years as a roaming special agent.

Possessed of a deft financial touch, the young Strauss purchased radio stations and real estate, parlaying his investments into a multimillion-dollar portfolio by the time he was 45.

His first major involvement in politics was as one of the top fundraisers for the 1962 gubernatorial campaign of his close friend John Connally, whom he met at college in the late 1930s, when Connally was student body president.

Connally first appointed Strauss to the Democratic National Committee in 1968. A year later, Strauss opened a branch of his Dallas law firm in the nation's capital.

A master in the art of backroom dealmaking, Strauss accomplished a major feat in 1968, when he succeeded in getting sworn enemies Connally, then governor, and Sen. Ralph Yarborough to campaign together for the national Democratic ticket.

Strauss' prodigious talent for campaign fundraising made him an influential member of the DNC. During his tenure as the party treasurer, he cut the debt in half. He later moved into the DNC chairmanship, a perch he used to help engineer Carter's 1976 election.

Strauss received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian award, in 1981.

His political apex came during the Carter years, where he was known as the president's "Mr. Fixit." Carter called on the skilled negotiator to serve as U.S. trade representative, his point man on inflation and as a special envoy to the Middle East.

In later years, however, the conservative Strauss found himself outside the inner councils of a Democratic Party that had become far more liberal than he. Friends and critics alike pointed to Strauss' unerring ability to remain close to whoever was in power, regardless of their politics.

After Carter's defeat in 1980, the departing president quipped: "Bob Strauss is a very loyal friend. He waited a whole week after the election before he had dinner with Ronald Reagan."