Gridlock in states: why they're mimicking D.C.

Loading...

| Harrisburg, Pa.

Hold the mirror up to dysfunctional Washington, D.C., and what folks in Pennsylvania see is their own state capitol. Different dome. Similar gridlock. The same could also be said of people who live in Illinois.

Both states are mired in gridlock as Republicans and Democrats in divided governments stare each other down. The standoffs have affected the most basic function of these state capitals – agreeing on a budget. After nine months of painful stalemate, Pennsylvania finally closed out its budget for its current fiscal year at the end of March. Illinois, alone in the nation, is still a holdout.

Since the last election in 2014, the number of divided state governments has nearly doubled, from 11 to 20. That is, the governor and at least one legislative chamber come from different parties. But today’s turmoil in state politics – led by Pennsylvania and Illinois but not limited to them – goes beyond that mere data point. What ultimately counts, analysts say, is how political leaders manage their differences.

“Divided government does not necessarily mean gridlock, and undivided government does not necessarily mean progress. In Massachusetts, Republican Governor [Charlie] Baker is getting more done with the Democratic controlled legislature than did his predecessor, Democratic Governor Deval Patrick,” writes Marty Linsky, at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, in an e-mail.

And behind dysfunction in Illinois are fiscal troubles that worsened during years of all-Democratic rule. A battle over unions is the sticking point now.

The rise in split governments at the state level results from a combination of factors.

- One cause is a growing partisan gap in America, seen in sharply divided viewpoints within the electorate as well as among politicians. A polarized climate in national politics has filtered somewhat into state politics.

- A second big issue is gerrymandered voting districts, which become ideological safe zones for politicians.

- A third factor is the way voter turnout trends can contribute to divided control of governorships and legislatures, according to a recent analysis by The Washington Post. Democratic politicians often do best in presidential voting years, when turnout is highest, while Republicans can roar ahead in off-year elections.

The costs of dysfunction

In these polarized times, divided government generally tends to narrow the scope of what gets done, shifting agreement to less controversial areas, such as fighting opioid abuse, which is getting attention in both Congress and the states.

But sweeping aside the big issues comes with a price. For one, unsolved problems get worse – costing Americans. They also have a political price – witness the success of outsiders in this year’s presidential primaries and the lack of trust in government.

Here in Pennsylvania, the stalemate has taken a toll, principally on schools and nonprofits that had to borrow or cut back their programs amid funding shortages. The state’s credit rating has been downgraded five times over five years. Politicians, too, have taken a hit.

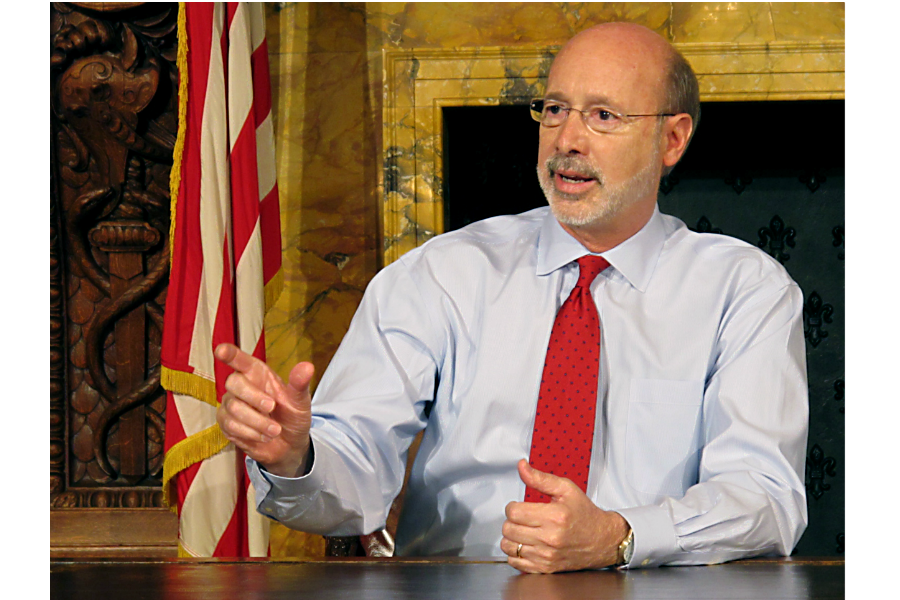

Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf’s job approval hovers in the low to mid 30s among voters, while the GOP-controlled legislature rates an even lower 11 to 15 percent, says pollster and political scientist Terry Madonna at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster. The college’s March poll shows voters rating government and politicians as the state’s biggest problem – by far – and more voters blame the legislature than the governor for the impasse.

Looking at how this showdown started, how it was resolved, and what that may portend for the future can be instructive.

Not unlike in Washington, the 2014 election produced a historically strong Republican legislature with an influential tea party wing. Its mandate: no new taxes. At the same time, Pennsylvanians handily elected a Democratic governor who promised to restore cuts in education funding by increasing taxes. He, too, claimed a mandate.

A war of the mandates ensued, played out on Pennsylvania’s political battlefield, in which the large Democratic urban areas of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh demanded one result, while the Republican rural areas in between sought another.

'Caustic' politics

But it was more than just competing mandates that tripped up the state. It was also the stepped-up political warfare.

Governor Wolf, a businessman who financed a lot of his own campaign, promised to be a “different kind of governor.” He was willing to play hardball, and when the legislature passed a no-new-taxes budget, he vetoed the entire thing, rather than just a portion of it. He was the first governor in decades to do that. To Republicans, it felt like a gut punch.

The legislature passed other budgets the governor didn’t like, but in December, the state Senate leader and the governor thought they had a compromise. Yet it fell apart at the last minute when, apparently, the ultraconservative wing in the House objected.

This time it was Wolf who felt the blow. He then went ahead with a partial budget veto – holding out about half of the funds for schools to keep pressure on the legislature to up spending on K-12.

Beyond the maneuvers were the words, zinged across Twitter and elsewhere.

Jennifer Kocher, communications director for state Senate Republican majority leader Jake Corman, describes the language from the governor’s office as “fairly caustic.”

Calling the GOP budgets “garbage” is not helpful when the next day legislators are asked to support tax increases, she says. To which the governor’s press secretary responds that the state is heading toward a fiscal cliff, with a multibillion-dollar structural deficit that can’t be wished away.

At last, as March drew to a close, the issue was resolved when the governor let a new supplemental budget lapse into law without his signature. The spending ordeal was largely put to rest – with no tax increases and a smaller total than Wolf wanted.

Not unusually in politics, the solution came when the pain of inaction got too bad and the political pressure too great.

How it got solved

A lot of school districts were talking about having to close if the budget impasse continued much longer, and a handful were in “imminent distress,” says Hannah Barrick, of the Pennsylvania Association of School Business Officials. They leaned on the governor to sign the supplemental budget that he had promised to veto.

The other pressure came from the governor’s own party. Shortly before Easter, 13 Democrats joined Republicans in the state House to approve the supplemental budget. It sent a signal that the votes would likely be there to override a promised veto.

“I don’t enjoy voting against my governor and leadership,” says one of the Democrats who sided with the GOP, Rep. Pam Snyder of Jefferson, in the southwest corner of the state.

But schools were about to close in her district, parents were worried about childcare, a fifth grader was about to lose her 4-H.

The time for holding out for a better budget deal was long past, Representative Snyder says.

“You can take the apple and take a bite out of it, or you can try to swallow it whole. And with the best of intentions, this governor has tried to swallow the apple whole in the first year.”

She points to her nine years as a county commissioner when they always passed their budgets in a bipartisan manner, balanced, and on time. “Everybody can’t win and get what they want. That’s not reality. That’s not real life.”

The governor and the legislature now have until July 1 to negotiate the next budget, and close a structural deficit of between $1.8 billion and $2 billion. Can they do it without another knock-down, drag-out fight?

Feelings are still incredibly raw, and Republicans may be tempted to view the governor’s “cave” as their “win.” And yet, an election is bearing down that could punish legislators if there's more dysfunction. Talks have already begun on the next budget, which is a hopeful sign given that there were long periods over the last nine months when no one was talking.

When asked about lessons learned, Jeffrey Sheridan, the governor’s spokesman, says he thinks it has sunk in among legislators that “we are heading toward a huge hole” in the next budget and it has to be fixed.

Stephen Miskin, spokesman for the House majority leader Republican Rep. Dave Reed, says he hopes the lesson has been learned never to veto a full budget – or to negotiate via social media in memes and tweets.

Notice that the two sides are talking about what they hope or think the other guy has learned. Nothing indicates a softening on either side, says Mr. Madonna, the political scientist.

Pennsylvanians, on the other hand, are very clear about the way forward. In the March Franklin and Marshall poll, 79 percent of voters supported compromise on the budget. And more supported a mix of cuts and tax increases, than just one or the other.

As Representative Snyder puts it: “You compromise in everything you do in life. If you’re married, you compromise. If you go to the grocery store, you compromise.”