What we know about Trump team Russia links – and why that matters

Loading...

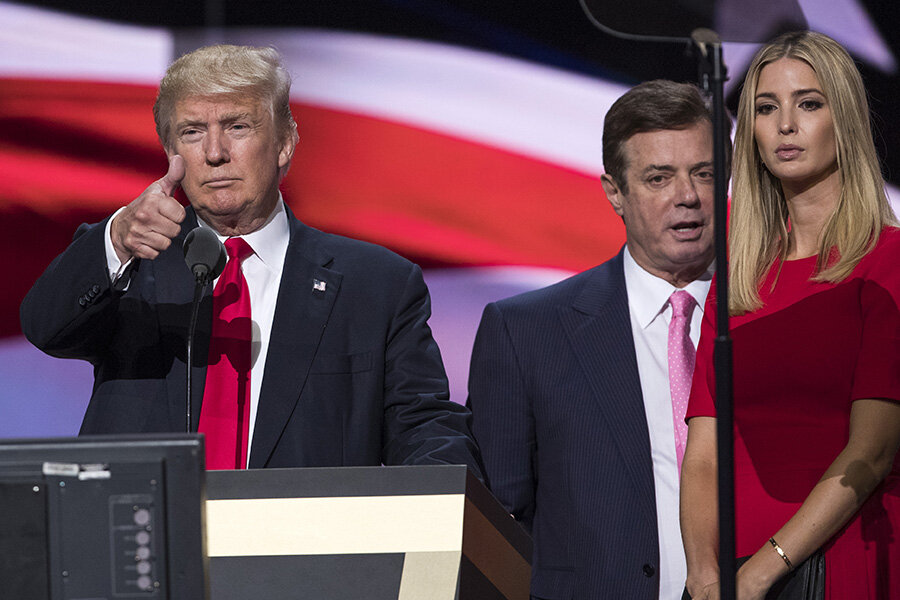

Paul Manafort was Donald Trump’s campaign manager for months in 2016. But the White House this week said his part in Trump’s winning electoral effort really wasn’t very large.

Mr. Manafort “played a very limited role for a very limited amount of time,” White House press secretary Sean Spicer said Monday at his daily briefing.

Ditto longtime Trump associate Roger Stone and former foreign policy adviser Carter Page. They were 2016 “hangers-on,” said Spicer.

And former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn was a “volunteer of the campaign,” said the press secretary, implying he was not someone the Trump team originally recruited.

Why does the administration feel a sudden need to distance itself from some past supporters? Because all the men mentioned had contact with foreigners that will attract FBI scrutiny as the bureau conducts its counterterrorism investigation into the possibility of coordination between the Trump campaign and Russia.

Trump officials almost certainly don’t know the full extent of the quartet’s interactions. Manafort in particular has been the subject of allegations linking him to shadowy pro-Kremlin figures in Ukraine.

Better to diminish the four men’s role in team Trump given such known unknowns.

“The reason they are doing it is it downplays it, makes their involvement seem less than it looks. And it plays into this larger pattern, where [Trump officials] basically say we’re going to try to control reality,” says Chris Edelson, an assistant professor in the department of government at American University.

Foreign contacts are common in political campaigns, especially for experts in international affairs, and aren’t on their face suspicious. But Manafort, as well as Messrs. Stone, Page, and Flynn are almost certainly in the first cadre of people who will draw FBI attention. If called to testify before Congress, it’s possible they would invoke the Fifth Amendment.

“My sense is they probably are already lawyered up,” says Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law.

No indication of guilt so far

This is not an indication they’re guilty of anything, of course. All have denied they did anything wrong, or that any of their foreign dealings were improper.

Manafort is a veteran Republican lobbyist and political fixer who took over Trump’s presidential effort in March 2016 and served as unpaid campaign chair until August. He resigned after the Associated Press reported that from 2012 to 2014 his firm had directed a covert Washington influence operation on behalf of Ukraine’s pro-Russian ruling political party.

On Wednesday, the AP further reported that a decade ago Manafort secretly worked for a Russian billionaire to advance the interests of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The work appears to contradict assertions by Manafort and the Trump campaign that he has never worked to push Russian government policies, according to the AP.

Stone is a longtime GOP operative and Trump associate who in the final months of the 2016 campaign repeatedly talked about backchannel communications with WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. He claimed to know in advance about forthcoming leaks of Clinton campaign emails from the group. US intelligence has concluded that Russian government hackers stole the emails to begin with.

Page is an oil industry consultant who candidate Trump listed as a foreign policy adviser last March. In July, he traveled to Moscow, where he gave a speech that depicted US efforts to promote democracy around the world as hypocritical, according to Rep. Adam Schiff (D), ranking member of the House Intelligence Committee. Page has denied serving as an intermediary between the Trump campaign and Russian officials. President Trump says he’s never met him.

Flynn is a retired Army lieutenant general picked as Trump’s first national security adviser. Administration officials say he was fired after they discovered he had not been forthcoming about his contacts with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak prior to taking office.

Steele links

The so-called “Steele dossier” ties all these men together. Compiled by Christopher Steele, a former British intelligence officer, this political opposition research document contains some outlandish allegations about Trump behavior. According to news reports, some parts have been verified by US intelligence, but others haven’t.

Representative Schiff of the Intelligence Committee used the dossier as the basis for much of his opening statement at Monday’s hearing with FBI Director James Comey. In terms of Trump and Russia, July and August of 2016 were the critical months, Schiff said.

In early July, Page traveled to Moscow for his speech. While there, he also met with Igor Sechin, the CEO of the Russian oil giant Rosneft, according to Steele dossier details. He was offered brokerage fees on a 19 percent sale of the company. Reuters has reported that since then a sale of 19.5 percent of the company has taken place. (Page has said this meeting and offer never occurred.)

At this point the Trump campaign was offered documents damaging to Hillary Clinton, published via a third party that would give both sides deniability, said Schiff on Monday, citing the dossier as his source.

Then Manafort, Page, and Ambassador Kislyak all traveled to Cleveland for the Republican National Convention. Prior to the opening gavel, a section of the GOP platform dealing with US aid to Ukraine was changed to make it more palatable to Moscow.

“Manafort categorically denies involvement by the Trump campaign in altering the platform. But the Republican Party delegate who offered the language in support of providing defensive weapons to Ukraine states that it was removed at the insistence of the Trump campaign,” said Schiff on Monday.

Then the Clinton emails started trickling out. Private cybersecurity firms conclude that the hack was the work of groups linked to the Russian government. Later in August, Stone tweeted “it will soon be Podesta’s time in the barrel.” That turned out to be true, as the release of Clinton chairman John Podesta’s emails continued to Election Day.

Coincidences or coordination?

It’s possible all these things are coincidental, said Schiff, wrapping up his lengthy Monday opening statement.

“It is also possible . . . that they are not coincidental, not disconnected, and not unrelated, and that the Russians used the same techniques to corrupt US persons that they have employed in Europe and elsewhere. We simply don’t know,” the California congressman said.

For his part, FBI Director Comey refused to give an opinion characterizing the nature of the connections before him. He said only that he was looking for evidence of “coordination” between Trump-related officials and Russian government representatives.

Comey said that in general the targets of an intelligence operation might not even know that they were dealing with actual government agents. Instead, they might have a relationship with a foreign businessperson, or academic, or student, or even a romantic partner, who unbeknownst to them was working as a spy.

“You can do things to help a foreign nation state . . . without realizing what you’re dealing with. You think you’re helping a buddy who’s a researcher at a university in China and what you’re actually doing is passing information that ends up with the Chinese government,” said Comey.

Comey’s overall reluctance to give many details about what the FBI is doing in this matter may be bad news for the Trump administration, according to Benjamin Wittes, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution and editor of the national security blog Lawfare.

That’s because Comey would be chattier about a probe that was wrapping up or didn’t seem that important. His reticence “means there is an open-ended Russia investigation with no timetable for completion, one that’s going to hang over Trump’s head for a long time, and one to which the FBI director is entirely committed,” writes Mr. Wittes in Lawfare.