Online media is replacing newspapers and TV. Is that a bad thing?

Loading...

| Washington

Call it two scenes from the new media revolution.

Scene 1: Room 233, the TV lounge on the second floor of American University's Anderson Hall dormitory, isn't exactly state-of-the-art home theater, but you could do a lot worse. There are dining tables, upholstered chairs, and a love seat all in front of a 42-inch Toshiba flat screen – and plenty of room.

At 6:30 on a pleasant April evening, as the opening bars of network evening news music play in living rooms elsewhere, the lounge is ... empty, except for one student having an in-depth cellphone conversation about his grade-point average. The TV is black. And as the minutes pass, the conversation rolls on: proof that if you want a quiet place to talk in a modern American college dorm, there may be no better place than your nearest TV lounge at the dinner news hour.

And it's not just the TV news that is largely forgotten here. There are no discarded sections of folded newsprint on the tables, either. Students at American get free copies of The New York Times and The Washington Post, but most don't bother – or they do so for different sorts of reasons. "I like the comics [in the Post]" says Susan Stine, a junior.

Scene 2: At the same hour, two miles away at the Sunrise Senior Living center, eight residents gather around their own big flat screen in a finely appointed, oak-paneled TV lounge: They watch C-SPAN quietly and intently. It is the very definition of single-task TV-viewing. Out in front of Sunrise, a man sits quietly in one of the rocking chairs that line the face of the building, studying The Washington Post. Cars whiz by on Connecticut Avenue as he slowly thumbs through the A section.

And up in their rooms, others tune into Katie Couric or Brian Williams or Diane Sawyer or Jim Lehrer to get a summary of the day's events. "I like to watch MacNeil/Lehrer," says Rhoda Alexander, a transplanted New Yorker, who calls the PBS NewsHour by the names of its previous co-anchors. "I watch Brian Williams, too. He's from my hometown."

There has been a flurry of reports about where Katie Couric will go when she leaves the "CBS Evening News" anchor position this month: A TV talk show? Maybe back to morning TV? But aside from the media's "Where will Katie go?" speculation, there is a more poignant question: How much do people really care?

There were, on average, 21.6 million people watching one of the three network evening newscasts in 2010, according to the Pew Research Center's Project for Excellence in Journalism. That's a good number, but it's 28.9 million fewer than watched in 1980. That drop is bad enough on its own, but consider the larger pool: There were 80 million more people in the United States in 2010 than in 1980. And though evening news viewership certainly isn't limited to the nation's senior centers, Katie, Brian, Diane, and Jim are well-known visitors in them. The median age of the nightly TV news viewer stands at over 62. So, in response to declining ratings at CBS, here we go again: another anchor shift aimed at bringing in younger viewers and bringing up ratings.

But regardless of who is in the anchor chair for any of the networks, they are bound to seem smaller in 21st-century America than they once did. The changes cascading through the news media have made the old models of news delivery – like, say, an anchor reading the news at an appointed time – seem archaic. And it is about more than just TV – newspapers, magazines, radio, all the "legacy" media are feeling the earth move beneath them. Journalists look out and see thousands of empty campus TV lounges and newsprint-less recycling bins and millions of iPads and smart phones and they wonder what's coming next.

For the public, the questions are deeper. What is the changing media landscape doing to the way the public gets news? What is it doing to the news itself? And what is it doing to the public as people?

The new day

In many ways Ms. Stine is the kind of young person news organizations dream about. She grew up in a house where The Philadelphia Inquirer was delivered daily, The New York Times came on the weekend, and the coffee table always featured the latest issues of The Economist and The New Yorker. And as an international relations student, she feels the need to keep up on the news. On her list of trusted, favorite news outlets – The New York Times, BBC, Huffington Post, and KYW (a Philadelphia radio station).

But all of those outlets – a traditional newspaper and TV network, a blog, and a radio station – are consumed on one device: her MacBook laptop computer, which is always at her side or in her backpack, wherever she goes.

"I get an e-mail every day from The New York Times. That's my first look at the site," Stine says. "Why would I get the paper? It's free [here], but it's big and bulky and there are no links – nothing to click on if I want more."

Walk across the campus or into a campus hangout like the Davenport Coffee Lounge and you will see faces lit by the dull glow of electronic screens, everything from laptops to smart phones, and not a sheet of newsprint in sight. The students click through Facebook, but also through news sites – The New York Times, The Washington Post – as they lounge and converse and sip. This is the modern news hub for your standard-issue 21st-century college student.

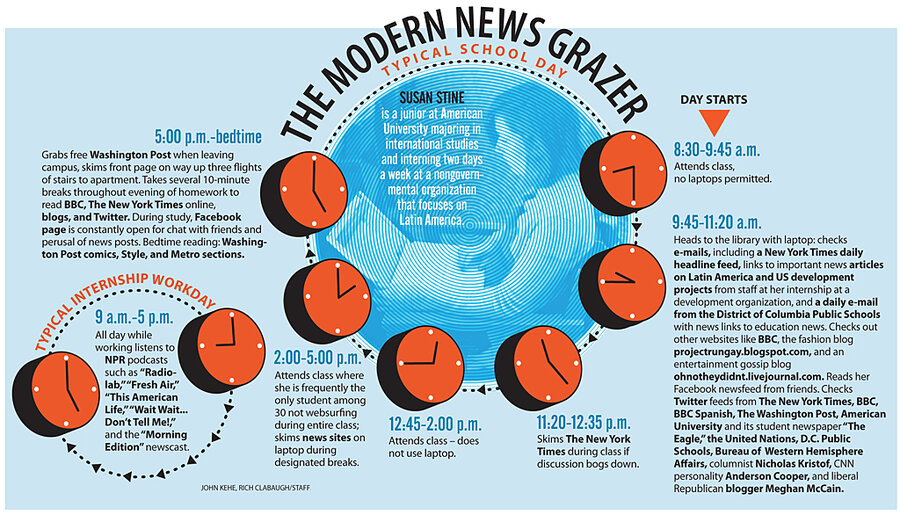

Stine says a normal day for her is rolling out of bed to catch an 8:30 class or go to work with little time to read the day's news. She catches up in an ad hoc fashion at odd moments. Her first check-in with headlines often happens in class, if things get dull, or immediately afterward between classes. She figures that over the course of the day, she opens her laptop 10 times and cycles through a list of outlets reading about Libya after her early class or about fashion after lunch. And, like other online news consumers, she has essentially created her own digital newspaper based on her quirks and interests.

The Susan Stine Daily? The "legacy media" are well represented in The New York Times, BBC, and radio station site KYW. But Huffington Post is there to offer some pointed opinion. There is also Project Rungay, a fashion blog. And for her fill of trashy celebrity pseudonews there is Oh No They Didn't – a website with the motto "The celebrities are disposable. The gossip is priceless." All in all, a nice smattering of most everything.

"And I always check in with Twitter and Facebook," she adds.

Water cooler or wire service? All news is social.

Twitter, 200 million users, and Facebook, 500 million, have become the new behemoths of the news media environment, particularly among younger users.

These sites, and other social-media sites like them, are more than ways to find out where friends are eating or hanging out, they are catalogs of news links. So along with her daily online "newspaper," Stine dips into the daily "newspapers" of other friends and their news of the day – stories they've read, blogs they've scanned, videos they've watched, which, combined, are the equivalent of personal news services.

Social media is a growing force in news consumption across the age spectrum, but it is particularly prominent among younger news consumer like the students at American University (AU). Almost 60 percent of those ages 18 to 29, according to a Pew Research Center survey, said it was important to be able to share "news content with others through e-mails or posting to other websites, like Facebook." That was much higher than any other age group.

And for some critics that raises real questions. Assuming our friends are a lot like us – or at least similar in outlook or background – what does this world of "friend approved news" mean for democracy? Are we, particularly the young, just talking to yes men to confirm our beliefs? In the age of customized news consumption, how does one reach outside one's intellectual garden for a broader perspective, much less get a complete picture of what's actually happening in the world?

But, all is not lost, says Tom Rosenstiel, director of the Project for Excellence in Journalism, far from it: "Young people get their news from friends through e-mail and social media, but the [news] links are usually to more mainstream outlets. It's stories from Yahoo, MSNBC, AOL, Google, and The New York Times."

So younger media consumers are not just trading links from Huffington Post on the left or Michelle Malkin on the right. They are going to the same sources their parents went to, just digitally – much like Stine. And, contrary to what other "older, wiser" news consumers might believe, they are actually fairly up to speed on the news.

"In 2008, the knowledge level of younger news consumers was even with the older folks," Mr. Rosenstiel says. "They are still interested in news, not just opinion. That's what the Web has shown us. It was the medium they weren't interested in, not the message."

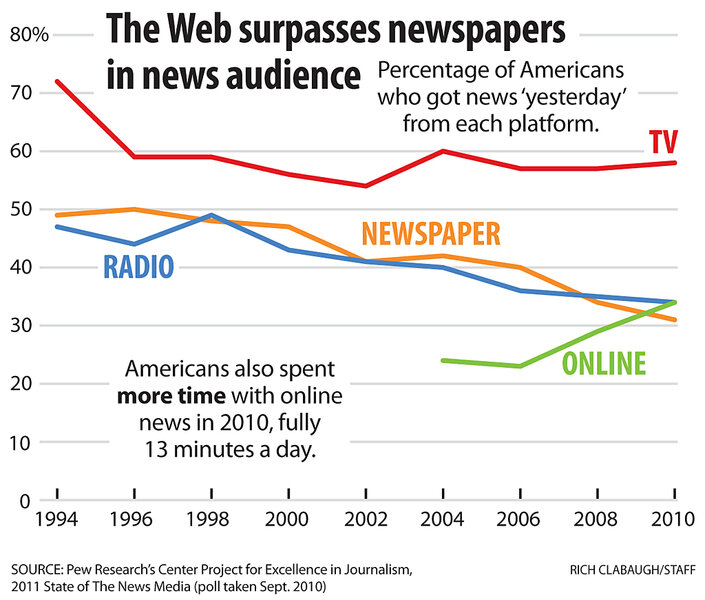

And younger people may be the vanguard, but the shift toward digital news reaches across age groups and across the entirety of the news media. In 2010, the only medium that saw audience growth was online. Everything else, from local TV news to cable to newspapers saw declines, some of them fairly steep. Cable TV audiences were down by more than 13 percent.

For older audiences, the technology itself is the draw. Young people may love their news online, but they probably find it harder to drop $500 on an iPad (and that's the cheapest model). The audience measurement firm comScore recently reported that 50 percent of iPad owners made more than $100,000 a year – not exactly student wages.

Two of the words most frequently applied to the iPad are "game changer." The slim relatively lightweight gadget makes the online reading experience much more like reading a newspaper of old – without the inky hands. And it has spawned a rush to the "computer tablet" market for computermakers. This year alone there will be dozens of tablets released by a range of makers – HTC, Acer, BlackBerry, Samsung. Many will be cheaper. Some are already under $200. And as the number of tablets in people's hands grows, the digital news revolution will take its next step.

There are real advantages to getting one's news on a tablet. Links are clickable. If you suddenly find yourself interested in a film review you can simply type a few words and watch its trailer. If you're unclear about events leading to, say, the conflict in Libya, help is a Google search away.

Add all that together and you understand the change will almost certainly be permanent.

What's lost, what's gained

But beyond all the chips and technology and social media, how different exactly is the new media world we have already half entered? Maybe not as much as you think.

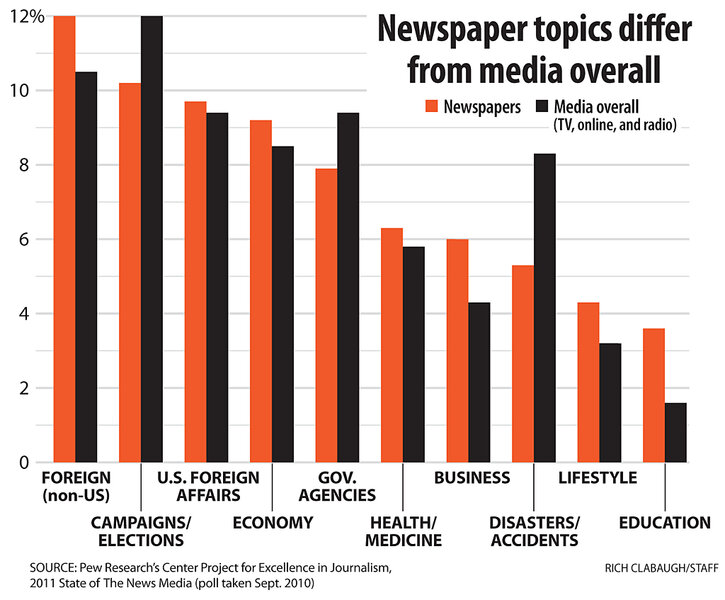

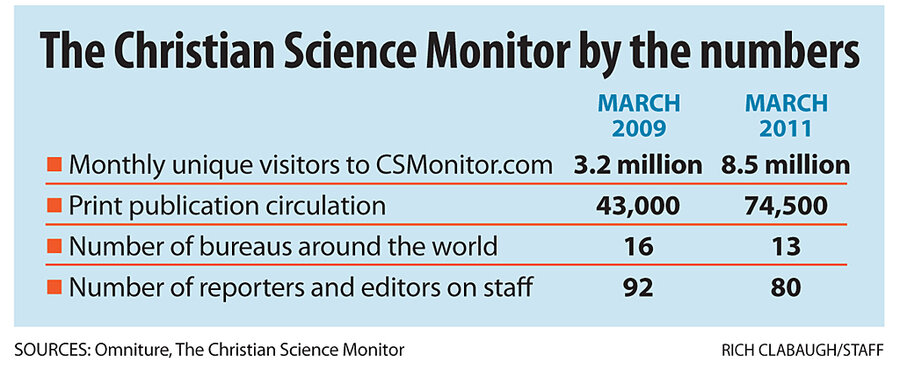

Despite the media focus on blogs and the far left and right, top news sites on the Web in the new media world look a lot like the old media world. In March they were, according to The Nielsen Company rankings for most popular current events and global news sites, in order: Yahoo News websites, CNN digital network, MSNBC, AOL News, NYTimes.com, Fox News digital network, Tribune Newspapers, Huffington Post, ABCNews digital network, and Gannett Newspapers and Newspaper Division. Yahoo and AOL may be new-media names, but they have some deep old-media roots. Yahoo has some original content (its own set of blogs) and some real editors deciding what is news on its site, but much of what is there also comes from the legacy world. And while AOL has waded into local journalism with dozens of small "hyperlocal" newsrooms spread across 18 states that it calls "Patch," underneath are a lot of stories drawn from the Associated Press and Huffington Post. It could be argued that the only true "new media" entry on the list is Huffington Post, which wants to put more money into Patch and act more like a legacy outlet. The next 10 top sites, by the way, look much the same with the Los Angeles Times, CBS News, and the BBC in the fold. (The Monitor was 47th in March Nielsen rankings.)

So the places where people get news are not astonishingly different.

What about the dangers of social media?

"I think it makes intuitive sense that the new media world, particularly social media, can create problems and change the way we learn about the world: the idea that you make your own echo chamber. But in a sense it has always been that way," says Michael Tippett, the Vancouver, British Columbia-based founder of the website NowPublic. "How much do you think Fox News carefully selects its stories? And we have always talked to friends about news."

Mr. Tippett is not exactly your average news consumer or a disinterested party. NowPublic is part of the new media environment, "a crowd-sourced, participatory news network that mobilizes an army of reporters to cover the events that define our world" is how it describes itself. But he raises an important point.

Now, instead of meeting your friend for coffee to talk about what he or she has been reading, watching, or listening to, you can just go by their Facebook wall or look at their Twitter feed. You can get straight into their heads without all that small talk.

"Oftentimes I go through my Twitter feeds and I am amazed by the diversity of what is there," says Tippett. "And I think, 'Wow, maybe my friends are more interesting than I think.' "

And there are other benefits to the new media consumption habits.

"Twitter has become a real-time link exchange, a short-form [freelance journalist] network," Tippett says. "Sometimes when my cable goes out at home I go to Twitter and search 'my city' and 'cable' to see what's there." If there are a bunch of entries saying that the cable is out, he knows that the outage is for the city or neighborhood; if not, he knows he needs to call the cable company.

It's also a zeitgeist detector, Tippett says, albeit one for the most wired news consumers. On April 24, the top trending items on Twitter in the US included "Savior," "Praise God" and "Felices Pascuas" (Spanish for Happy Easter). Certainly a reading of some kind of sentiment on a quiet Easter Sunday. This is the impact of social media on news, Tippett argues. It's really just old media-plus, and who could be against that?

In fact, when you look at all of it – people turning to reliable news outlets with constantly updated headlines supplemented by crowd-sourced news and links from friends to stories you might have missed – you might wonder what exactly there is to be afraid of in the new media culture. Could it be we are walking into a new news utopia – anchor chairs and newsprint nonwithstanding?

Not completely. There are some serious growing pains coming out of the way we increasingly get our news.

Who'll do the reporting?

One of the biggest and potentially most troubling aspects of the new-media culture is the cuts that have come to news organizations of all forms around the country due to lost revenues. The rise of the digital outlets through laptops and tablets and smart phones has left a gaping hole in revenues for news outlets.

The Web, in the form of Craigslist and similar sites, has destroyed classified advertising for newspapers while falling circulation hurts commercial print ads. The disappearing and aging audiences from the evening news have meant reductions there as well. The ads heavily weighted toward ailments of all sorts and their medications can make the viewer feel like a pharmaceutical convention is taking place on their televisions.

In the past four years, newspaper revenue has dropped 48 percent. Network TV saw a better 2010, but the trend since 2000 is unmistakably down – or up only because of staff cuts.

And that's one of the most serious challenges of the new media world. There is money spent in advertising online, but much of it is spent on search advertising, and that money does not flow into newsrooms, but rather to the Googles and Yahoos of the world. Online revenues for the legacy media have not been able to keep pace with the loss of revenues that have come with shrinking audiences. The result: smaller staffs.

The Project for Excellence in Journalism estimates that newspaper newsrooms, on the whole, are 30 percent smaller than they were in 2000. ABC News cut its staff by 25 percent last year. CBS News slashed its personnel by 75 people. And cuts for both those news divisions came after cuts earlier in the decade.

What's more, all those cuts come as we enter this age of round-the-clock news updates – which actually requires more staff. So staffs are pushed to do more with less year after year. Eventually, maybe even now, those cuts will have an impact on the constant headlines on phones and iPads. It's hard to know the stories you are missing until a news event blows up and you think, "Why have I not heard of this before?" Maybe it's because your friends on Facebook didn't link to stories about it in the past, but it also may be that there simply weren't any stories about it.

Until the news media can solve the online revenue problem, it's hard to imagine how they will have the money to invest in more reporting.

That's why The New York Times's experiment in charging users for online content is being watched so closely by other newsrooms. The system is complicated – the first 20 articles a month are free of charge, then users can pay $15 every four weeks for access to the website and a mobile phone app, $20 for website access and an iPad app, or $35 for an all-access plan. And of course, all that digital access is free of charge with a subscription to the paper version. But it is important because it flies directly in the face of the Web ethos that everything should be free of charge.

Should the Times succeed, it might pave the way for other outlets to find a way to regain years of losses. That's critical, because if the news media can't find a way to fill the revenue hole the Web has created, all the tablets in the world won't save news. And all the customized news consuming may actually offer more in terms of convenience, but less in terms of content than in those good old-media days.

Who will we be?

But on top of the questions of revenue there is this: Who are we becoming in the new media world? We have news at our fingertips on smart phones we can scan at a lunch counter. We can watch the news when we want instead of making an appointment to sit down with a network anchor in our living rooms. We have what we want, when we want it.

And that's good, right?

What is really lost in the new media-consumption world is setting aside time for news. The people at Sunrise Senior Living treat news as a meal. They sit down and take their time and take it in. The students at AU are news grazers, taking in a bit of this and a bit of that as they can – and they offer a glimpse of the future.

As Americans have grown busier, new technologies have found ways to fit the news into tightening schedules and, in the process, they are blurring the lines between different parts of their lives.

It's similar to the way e-mail on mobile devices has blurred the lines. You are always in the loop. With news today, the most important events of the day don't arrive neatly bundled in the paper at breakfast or neatly packaged on TV over dinner. News is a never-ending torrent of information: It's up to you when you want to sample it.

And that can be wonderfully liberating ... or an affliction. We've come to discount having time for things in America. As our lives have sped up, most things, it seems, are sandwiched between other things. Lunch is something between meetings; and while we are waiting for our friends to show up at the restaurant, we scan our e-mail and catch up on correspondence we missed on the five-minute walk over. News is just another item on an overpacked personal agenda – as if every scan of the headlines is a box to check off. We're all individual local news radio stations now: "Give us five minutes with our iPhones and we'll give you the world."

What's lost is reflection: Headlines pass in front of our eyes and they are gone as we leap to the next story.. Education experts tell us, increasingly, that making it in the world is about contextualizing and analysis, and we increasingly don't give ourselves time to do it.

Is that really where the digital news revolution is leading us – a few Google headlines on a coffee break, a few Facebook links before work, and maybe a few YouTube videos before bed?

"The future is already here, it's just not evenly distributed," chuckles Tippett, quoting science-fiction writer William Gibson.

Does that mean soon everyone will be constantly checking their Twitter feeds and visiting their favorite news sites to get an understanding of the world?

"No. This is still all new to us, and we're in a manic phase right now," says Tippett. "We're in the 'I want it all, I want it now' phase. But eventually we'll come out of it. It'll settle down."

In other words, it's probably going to be up to us to apply the brakes. For his part, Tippett, who loves the new media world, says the key is self-control, and he has placed some controls on himself. He uses his tablet to read more books than ever, he says. He rarely watches TV, and he allows himself to check his e-mail only twice a day – regardless of what story links it may hold.