Who's filling America's church pews

Loading...

| lewiston, maine

On a snowy 20-degree day in December, the visitors shiver as they move among vestiges of a long-closed Pizza Hut on this city's struggling main street. A salad bar teeters off kilter. Dust collects on the dismantled facade of a soda dispenser. A few bolted-down tables and chairs remain – usable, but only after a good cleaning.

Yet none of this bothers the three leaders from the Auburn Seventh-day Adventist Church, who seem warmed by holy fire to carry out their task: Help transform the pizza joint into something with a bit more piety. Their church has reached capacity, having doubled attendance in the past year. So they've crossed the Androscoggin River to plant a second church, the Ark, in the heart of one of the nation's least religious states.

This won't be worship as usual. Starting early in the new year, a smorgasbord of community services will be served where deep-dish pepperoni used to be the lure. Vegetarian cooking classes and health seminars, hydrotherapy treatments and massage instruction, marriage classes and smoking-cessation clinics – all will be free of charge and led by volunteers. A vegan restaurant will open to bring in revenue. Worship services will begin next spring.

"It's almost like you have to use a place like a Pizza Hut," says Tracy Vis, a new member of the Auburn church. "Some people are not going to be comfortable with [traditional church buildings] or traditions. But they'll come here and listen to these different messages."

The Ark is symbolic of a transforming religious landscape in New England. Long defined by dominant Roman Catholic and mainline Protestant institutions, the terrain is undergoing a fundamental shift as traditional denominations cope with steep declines in membership and shutter churches and seminaries.

At the same time, evangelical and Pentecostal groups are doing just the opposite. They're expanding their footprint in what statistics show are America's four least religious states: Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Massachusetts. And because more and more Americans today identify with no particular religion, what happens in this land of spiritual free agency could offer insights into the future of religion across the country. The recent changes in New England have been significant:

•Between 2000 and 2010, the Catholic church has lost 28 percent of its members in New Hampshire and 33 percent in Maine. It has closed at least 69 parishes (25 percent) in greater Boston.

•Over the same period, the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) established 118 new churches in northern New England, according to the 2010 Religion Census. About 50 of them inhabit buildings once owned by mainline churches.

•Other denominations are growing, too, including Pentecostals: Assemblies of God (11 new churches in Massachusetts) and International Church of the Foursquare Gospel (13 new churches in Massachusetts and Maine). The Seventh-day Adventists, an evangelical group, opened 55 new churches in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine between 2000 and 2010, according to the Religion Census. Muslims and Mormons are experiencing membership gains as well.

More change looms on the horizon. In 2013, northern New England will lose its only mainline Protestant seminary and accredited graduate school of religion when the Bangor Theological Seminary closes in May. Three months later, Southern Baptists will open Northeastern Baptist College – the first SBC-affiliated pastor-training college in northern New England – in Bennington, Vt.

"The old establishment is crumbling in the sense that fewer people are going to church and buildings are being sold off," says Todd Johnson, director of the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in South Hamilton, Mass. "The old expectations aren't there anymore, and that creates an openness to new brands."

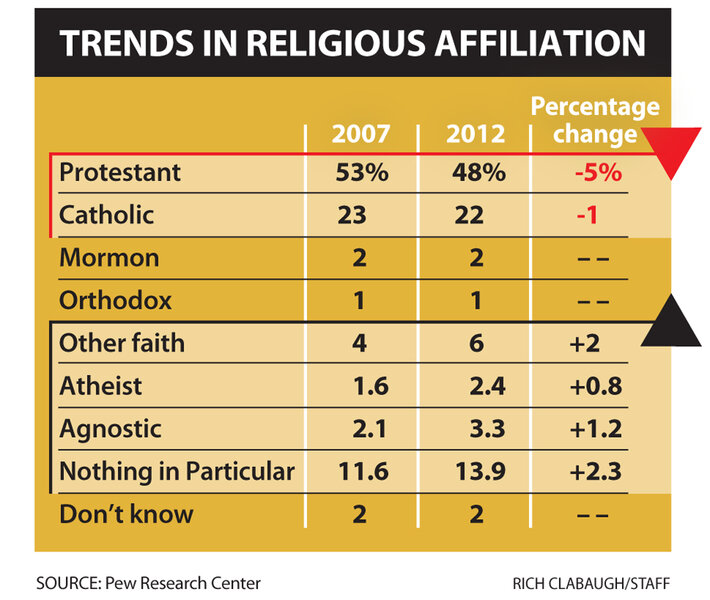

New England's changing religious character comes as religious ties decline around the country. Nearly 1 in 5 Americans (19.6 percent) now says he or she has no religious affiliation, up from 15 percent just five years ago, according to Pew Research Center surveys.

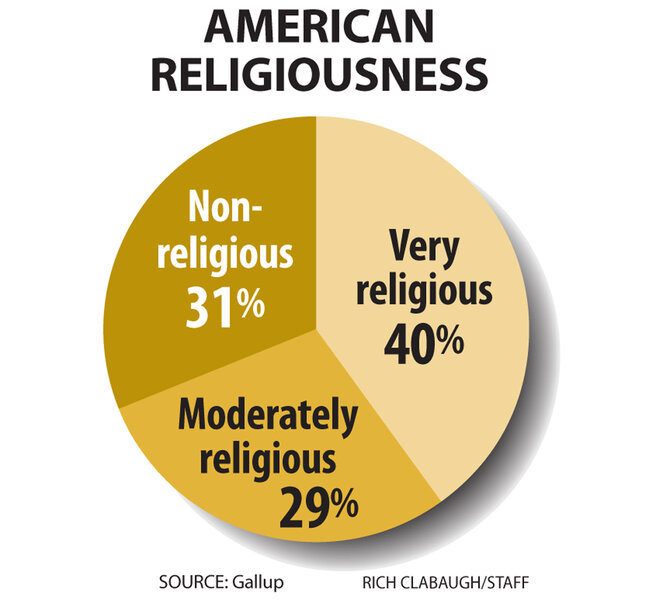

Faith remains strong: More than 90 percent of Americans still believe in God or a universal spirit, according to Gallup research, even as fewer claim a particular religious "brand" or identity. More people are opting not to align themselves with one religious denomination or tradition, but their interest in faith remains keen and creates opportunities for innovators.

"The way people are religious is changing," says Frank Newport, Gallup's editor in chief. "And maybe what's happening up in [New England] is a good indication of what is happening or could happen elsewhere."

Now emerging in the land of Cotton Mather and Robert Frost are religious cultures marked by immigrant experiences and creative worship, with emphasis on good works and personal holiness. It's not entirely what stolid New Englanders are used to, but maybe that's its appeal.

* * *

On a December morning, the polished sounds of bongos and electric keyboards emanate from Congregación León de Judá, a 1,500 member church in an ethnically diverse Boston neighborhood. It's a mainline American Baptist Churches congregation, though maybe not one prior generations would recognize.

The 36,000-square-foot complex looks more suited for offices than offerings, but on this day, 500 pack the sanctuary for an upbeat, bilingual service. A high-stepping man leads a praise chorus. Laypeople take turns praying: one in Spanish, then another in English. Dozens approach the stage for prayer. Hands rise and eyelids fall. After an hour, some 75 English speakers representing 15 countries head downstairs to continue worship in their language.

Another 15 go to a window-filled room where a new Anglican Church in North America congregation, started by León de Judá, is gathering for the first time. Ministries here are growing so fast – 500 new members in the past five years – that a 40,000-square-foot building is rising next door to help house it all.

For new members like Ted Best, who emigrated from Barbados 30 years ago, and William Leslie from Dominica (both English-speaking countries), the church's Hispanic roots were no barrier. They like being part of a dynamic congregation that provides outlets for compassion and immigrants' hopes.

"We want to be part of a church that is growing," says Mr. Leslie, who does outreach work for León de Judá, from visiting hospitals to sharing information in subways. "We want to touch the community for Jesus, and this church has advanced that cause."

Much of the church growth in secular New England stems from immigrants and the cultures they create in pursuit of spiritual grounding. Researchers at the Emmanuel Gospel Center (EGC), a Boston-based Christian organization that studies urban ministries, call it a "quiet revival." It is often overlooked because the Religion Census tracks only denominations, yet nondenominational churches account for some of the fastest-filling pews, or folding chairs, as the case may more often be.

EGC data show that Boston has spawned more than 100 Hispanic evangelical churches in the past 40 years, up from just a handful in the 1970s. EGC's census also found 65 Haitian churches in greater Boston, including at least one with more than 500 members.

"A storefront church might not look that big, but they have 100 to 200 people coming each week," says Rudy Mitchell, a senior researcher at EGC. "A big old church might only have 50 people attending even though they have a big building."

Where growth is happening inside traditional denominations, such as at León de Judá, immigrant connections often play a central role. Half of the Southern Baptists' 325 churches in New England are non-English speaking. They worship instead in Spanish, Portuguese, or Haitian Creole.

What's more, internationally minded denominations are benefitting from having built churches, schools, and hospitals abroad for decades. Seventh-day Adventists operate more than 7,800 schools around the world. Thus, Brazilians who immigrate to Massachusetts often plug into a local Seventh-day Adventist church led by an immigrant pastor who knows their homeland and speaks their native language, according to Edwin Hernandez of the Center for the Study of Latino Religion at Notre Dame University in South Bend, Ind.

Immigrant vitality is driving growth in other more secular regions as well. Steve Lewis, academic dean at Bangor Theological Seminary, spent most of his career in Oregon, the sixth least religious state.

"The growth in churches in areas that are generally in decline are coming from ethnic congregations," says Mr. Lewis. "In Portland, Ore., there are churches with Romanians, Ukrainians, Eastern Europeans, and thousands of people go to them. You have churches in decline in that region, but these [ethnic] churches are buying warehouses and remodeling them."

Many of the religious groups with international ties investing in steeples and schools in New England are reaping quick returns. Since relocating from Rhode Island to a long-vacant campus in Haverhill, Mass., in 2008, the Assemblies of God's Zion Bible College has doubled enrollment, from 200 to 400.

"People don't like the aura of past religions in many cases, where the church looks like it's a club," says Charles Crabtree, president of Zion, which will be renamed Northpoint Bible College on Jan. 1. "But when we go out, build churches, and are in the neighborhoods expressing the love of Christ, it's amazing how many people respond."

In Westbrook, Maine, the Seventh-day Adventists last year acquired a new regional headquarters – a 14,500-square-foot library. In Northfield, Mass., near the Vermont border, a 217-acre campus will be handed to a Christian institution in 2013 as a gift from Oklahoma's Green family, billionaire owners of a craft store chain, who bought and renovated the property in order to give it away.

Some churches that offer an alternative to prevailing regional values, in both New England and around the country, are attracting new disciples. Liberal Unitarian Universalists have seen some of their fastest growth in recent years in Oklahoma, Tennessee, and other conservative Southern states.

In New England, the converse is true. Churches that echo the prevailing culture's moral relativism and liberal sensibilities sometimes struggle to differentiate themselves. Yet when a doctrine-minded pastor like Joey Marshall unpacks the Bible, verse by verse, many people yearn for his unflinching message. To accommodate growing numbers, Mr. Marshall's Living Stone Community Church in Standish, Maine, moved from a traditional 50-seat structure to a former paintball facility.

"A lot of people were looking for a church that still preached the Gospel and were having trouble finding a good, solid, Bible-believing church," says Marshall, a Southern Baptist from Tennessee. Former Catholics make up about 40 percent of his flock, he says.

In terms of tactics, Southern Baptists have tapped missionary-minded activists ("catalysts") in the South to galvanize more resources and volunteers especially for "unchurched" New England. They've also hired a full-time staffer to evaluate acquisition opportunities when churches want to sell or donate their buildings.

Two years ago, the SBC's North American Mission Board (NAMB) put 20 percent of its resources into establishing new churches. Now it spends 45 percent on church planting. It's part of a larger effort to focus on urban areas.

"In the 1950s, we pulled out of the cities," says Aaron Coe, NAMB's vice president for mobilization. "But we've since realized the world is a very urban place, and if we're going to make a difference in the generations to come, then we're going to have to seriously engage the cities."

* * *

Tensions have flared up occasionally over some of the religious expansionism. This past March, when it looked like the free Northfield, Mass., campus might go to Jerry Falwell's Liberty University, a group of local residents launched a website to let others know about the evangelical institutions looking at the site.

"What makes [Liberty] a really bad fit is the matter of bigotry against certain groups, [namely] gays and lesbians," Northfield resident Nancy Champoux, a retired middle school teacher, said at the time. She also worried that new neighbors on the religious right might replace hundreds of trees with wide roads and clearings, as Liberty did in building its Lynchburg, Va., campus.

Up the road at the Congregational Church in West Dover, Vt., the Rev. Emily Heath bristles when others regard areas like hers as "the new mission field." "We are not the mission field," Ms. Heath wrote in a July open letter in The Huffington Post. "Don't come here telling us we are not really Christian, or spreading falsehoods about the state of our beloved churches, or calling our neighbors sinners. We don't like that."

Southern Baptist church planters, however, say they bring a spirit of compassionate service rather than confrontation. One popular way they try to introduce a church: Pay a local gas station to drop its prices by 25 cents per gallon for two hours on a Saturday. During the promotion, church members wash windshields and hand out religious information about the new church.

"People [getting gas] say, 'What in the world is going on?' " says Jim Wideman, executive director of the Baptist General Convention of New England. "So they'll have a little card that says, 'we're just trying to show the love of Jesus to you in a practical way.' "

Church activists, of course, ultimately want to impact more than gas prices. In secular areas such as the Northeast, they also strive to "influence the influencers," since the region shapes attitudes nationwide through such channels as education, policy, and media. The Southern Baptists' "Send North America" campaign says church planters "recognize the potential of harnessing the influence of the area" to help spread the Gospel.

While some might even hope the religious incursions in New England would foster a more GOP-friendly atmosphere, church leaders make no such promises. Many see Christians as increasingly willing to accept minority status in America.

"Most of those who believed in the '70s – the whole Moral Majority thing – that there was a chance that America really could become a Christian nation have given that up now," Mr. Wideman says. "They have said, 'We need to begin to think like Christians in the 1st century thought, when they were definitely a minority.' "

* * *

Other churches are trying to keep politics as far away from the pulpit as possible – and are thriving. Stephen Um is the Korean-born pastor of the Citylife Church in Boston, a 10-year-old Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) congregation that meets in a hotel and attracts 800 weekly attendees. He ministers to Boston's youthful and professional elite: 35 percent of his half-white, half-Asian congregation has at least one postgraduate degree.

But his ministry focuses on empowering individuals to bear witness, challenge atheist assumptions, and do good works – not change public policy for Christ.

"This is not a political movement," Mr. Um says. "We want to be the best citizens that we can be.... I tell them that the best way for you to have a witness as a Christian in the workplace is to pursue the common good, to work with integrity ... to love your neighbor."

Churches that have equated faith with political activism, in fact, are watching their ranks thin. Lewis, the Bangor Seminary dean, sees emphasis on politics as one reason some mainline denominations have seen their membership decline accelerate in the past 10 years.

"In the mainline denominations, liberalism is dead, but they just don't know it yet," says Lewis, an ordained Methodist elder. "Liberalism has moved so far toward the social consciousness [agenda] that it's lost its spiritual roots. What they need [in the mainlines] is a passionate spirituality."

For their part, Roman Catholics haven't complained about religious opportunists encroaching on what's been largely their turf since the late 19th century. One reason is that the Catholic Church will remain the region's largest religious player for many years to come, Mr. Johnson notes. Catholic commitment might even be growing significantly in pockets, he adds, but the signs are hard to notice since they're overshadowed by declining regional numbers.

To fill more pews, Catholics are focusing on bringing inactive members back into the fold. In January, the Archdiocese of Boston kicks off "Disciples in Mission," an effort to reinvigorate parish life by encouraging Catholics to attend mass more regularly, receive the sacrament of reconciliation, and inspire boys to explore the priesthood.

"If we're doing our job of inviting Catholics back to church, [and] if we're being welcoming, praying about it and giving witness," says the Rev. Paul Soper, director of the Office of Pastoral Planning for the Archdiocese, "then that's going to have an effect on the broad religious landscape, including specifically people who traditionally have been Catholic but now are seeking other ways of worshiping and living."

* * *

What's emerging, it seems, is a religious shift whose wider meaning is best measured not so much in terms of political or cultural transformation, but in how faith is practiced. Adherents are flocking to churches where the difference faith makes is concrete and visible. Connections fostered in faith communities are enabling them to live in keeping with their aspirations and nurture freedoms they've come to discover.

Take the 40 newcomers to the Auburn Seventh-day Adventist Church in Maine. Interviews with many of them revealed a common theme: Each was enjoying some type of new freedom and felt the church could help keep them on the right path.

For Phil and Pat Webber of Lisbon, freedom has involved leaving a Jehovah's Witness community that they say restricted them from talking with family members or socializing with certain friends. Ben Dugas of Auburn, who has a condition diagnosed as cerebral palsy, finds he sleeps better and enjoys more time with his wife, Wendy, since adopting the church's guidance on vegan eating and Sabbath-keeping.

Debbie Giroux, from the town of Poland, found freedom from love addiction and codependency through a 12-step group, she says, and knew she needed to worship the God who had liberated her. "I was filled with shame, toxic shame; then with the 12-step program, I just woke up one day and that was gone," says Ms. Giroux. "It chokes me up. That built my relationship with God. And through that process, this little voice in my head kept saying, 'you need to go to church.' "

At Congregación León de Judá, Kelvin Carroll has found a path for continuing enrichment that began in Alabama. He'd long worshiped in emotional black Baptist churches, he says, but discovered more dimensions to faith when he joined a biracial church in Dothan, Ala., led by two pastors, one black and one white.

Now a transplant to Quincy, Mass., where he works 14-hour days at Wal-Mart and Home Depot, Mr. Carroll expects he'll learn even more about the Bible and discipleship through an English ministry hosted by a Spanish-speaking congregation. "I'm here because I wanted to see the Spanish part of it," says Carroll. "It helps me in the ministry to know each culture and how they serve God."

Even in some churches experiencing fewer people in the pews, activity in the name of God is thriving in other ways. The Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire saw average attendance drop 20 percent from 2000 to 2010.

"The churches and the pews have been emptying, but they're starting to come back," says the Right Rev. Robert Hirschfeld, who will become Episcopal Bishop of New Hampshire in January. "Maybe not on Sunday morning, but I see people coming together for prayer groups, for Bible study, for partnering together to serve those who are most at risk in our society. When you look at those metrics, the church is very alive."

It is alive on Sunday mornings and afternoons, too, in buildings that don't look like churches. No steeple or stained glass adorns León de Judá, but that doesn't keep the people from rejoicing. "Where the Spirit of the Lord is," sings the hand-waving congregation as a projector displays lyrics on a wall, "there is freedom."