Does Olympic gold light a path to riches? Not for everyone.

Loading...

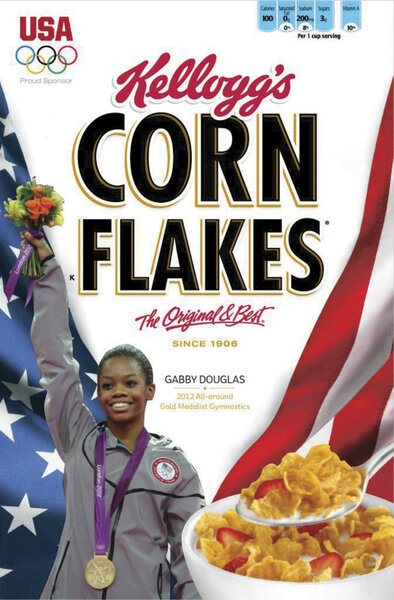

No sooner had Gabby Douglas dismounted from the podium clutching gymnastic gold, then observers began speculating on the other riches she’d be pulling in from corporate marketing deals. Her face already graced the boxes of Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, and that was just the beginning.

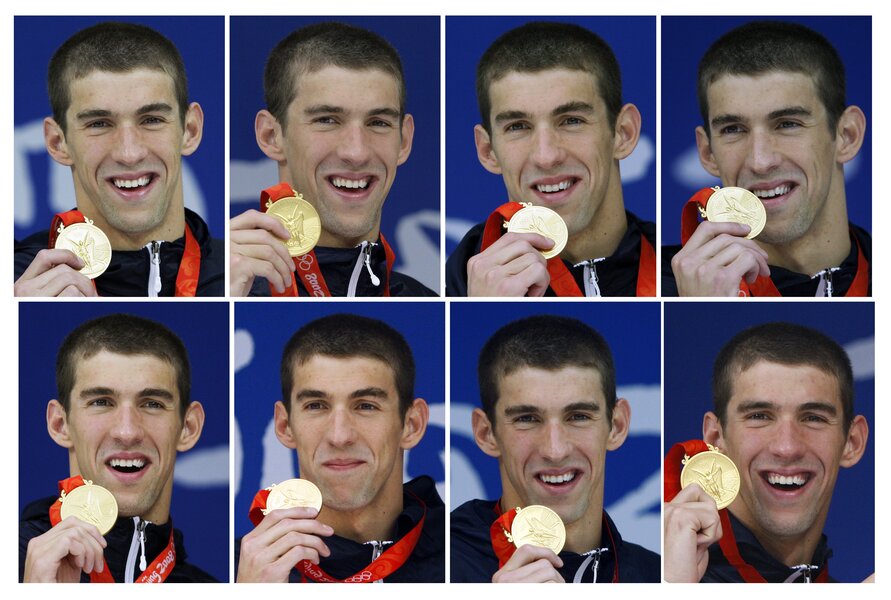

Every four years, it’s same the story: an athlete wins a high-profile event, and the buzz starts about the millions of dollars to be raked in from corporate sponsorship deals. For US high achievers like swimmers Michael Phelps and Ryan Lochte and gymnasts Aly Raisman and Ms. Douglas or their peers from other nations – here's looking at you, Usain Bolt – the Summer Olympic Games look like a financial bonanza. The fame of gold medals could be worth as much as several million dollars per year.

But these tales of personal riches are the exception, not the rule. Of all athletes, Americans enjoy some of the richest potential for reaping income from corporate sponsorships and product endorsement deals. But the flow of money is uneven and sometimes comes with pitfalls.

Take the example of US hurdlers Lolo Jones and Dawn Harper. Their excellence is in a sport that, unlike tennis or basketball, enters the TV limelight only once every four years.

Ms. Jones has had more success with corporate sponsors than Ms. Harper, who was a gold medalist in Beijing. That contrast served as the backdrop when Jones found herself this week in a negative spotlight for the financial side of her career. A New York Times article painted Jones as an athlete whose "sad and cynical marketing campaign" has made her more visible than teammates who are better performers on the track.

Jones, who crashed over a hurdle and out of gold contention in 2008, said she had been "ripped to shreds" by the criticism, which she called unfair. In the end, she proved to be a contender in the 100-meter hurdles, finishing fourth and just a tenth of a second out of a bronze medal. Harper again medaled – silver – while Australian Sally Pearson won gold and US teammates Kellie Wells got the bronze.

The big story here is not whether Jones deserves to have more sponsors than Harper. It's the more basic point: Like Harper, most Olympic athletes aren't rolling in money. The corporate deals that do come their way (Harper is backed by Nike) enable their athletic quest but not a cushy lifestyle.

This reality came into view early in the London Games, when many athletes used the social network Twitter to publicize their protest against an International Olympic Committee mandate known as rule 40. The rule says athletes can't advertise for their sponsors during the two weeks in London, unless the company is an official sponsor of the Olympics.

US track and field athlete Nick Symmonds, among others, tweeted that "many have gotten rich using Olympic athletes' free labor." He and others made the case that athletes would be valued more highly by corporations if their marketing visibility could extend to the Olympic Games themselves. That, in turn, might give more athletes the means to train and compete in their sports.

A few superstars, inevitably, become the most visible in ads targeted at the mainstream. For Ms. Douglas and Ms. Raisman, who have become instant household names, the first offers are likely the start of a flood of opportunities.

Mr. Phelps already enjoyed a ubiquitous presence even before these Games. Now, with his London performance making him the most decorated Olympian ever, he stands to rake in big money for years to come.

Sometimes, young athletes face tough choices about whether to accept corporate cash or not.

Missy Franklin, who may be the US women's answer to Phelps in the swimming pool, has launched her Olympic career by winning four golds and a bronze (plus setting two world records) as a teenager in London.

Sports marketing experts say Ms. Franklin might earn $2 million a year or more by saying "yes" to companies that want to hitch their products to her rising star.

Yet her avowed interest, so far at least, is to pursue college-level competition, where amateur-only rules ban such income.