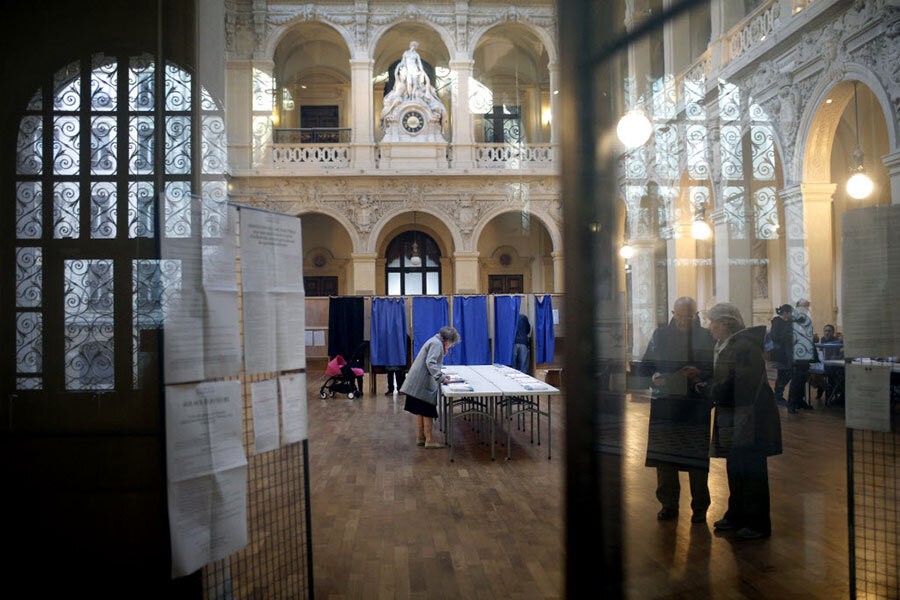

France goes to vote in regional elections

Loading...

French voters are casting ballots Sunday for regional leaders in an unusually tense security climate, expected to favor conservative and far right candidates and strike a new blow against the governing Socialists.

Islamic State-inspired attacks on Paris Nov. 13 and a Europe-wide migrant crisis this year have shaken up France's political landscape.

Marine Le Pen's anti-immigration National Front is hoping the two-round voting that starts Sunday will consolidate political gains she has made in recent years — and strengthen its legitimacy as she prepares to seek the presidency in 2017.

The unpopular Socialist president, Francois Hollande, has seen his approval ratings jump since the Paris attacks, as he intensified French airstrikes on Islamic State targets in Syria and Iraq and ordered a state of emergency at home. But his party, which currently runs nearly all of France's regions, has seen its electoral support shrivel as the government has failed to shrink 10 percent joblessness or invigorate the economy.

"There will be a 'punishment vote' for sure" against the Socialist government, said Parisian voter Daniel Vernet.

Voters are choosing leadership for the country's 13 newly redrawn regions in elections that start Sunday and go to a second round Dec. 13.

The regional vote has taken on greater meaning in the wake of the Paris attacks. Many political leaders are urging apathetic voters to cast ballots as a riposte to fundamentalists targeting democracies from France to the United States.

However, turnout was just over 16 percent at midday, barely higher than during regional elections five years ago.

First-time voter Eli Hodara, an 18-year-old Paris student, expressed hope that more young people would turn out. "I think it is important to vote even if one leaves the ballot blank."

It is the last election before France votes for president in 2017, and a gauge of the country's political direction.

"It's an important moment, important for the future of our regions, important also for the future of our country, important with regard to the catastrophic and dramatic events that have hit France," Le Pen said as she cast her ballot in the northern city of Henin-Beaumont.

Le Pen is campaigning to run the northern Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie, which includes the port city of Calais, a flashpoint in Europe's migrant drama. Polls suggest she could win.

Her young niece, Marion Marechal-Le Pen, appears to be on even stronger footing in her race to lead the southern Provence-Alpes-Cote d'Azur region, including the French Riviera and part of the Alps.

A win for either would be unprecedented in France, for a party long seen as a pariah.

Socialist Prime Minister Manuel Valls and the conservative-leaning national business lobby issued a public appeal this week to stop the National Front's march toward victory. Le Pen has worked to undo its image as an anti-Semitic party under father and co-founder, Jean-Marie Le Pen, and has lured in new followers from the left, the traditional right and among young people.

The arrival of hundreds of thousands of migrants in Europe and the exploits of IS, which has claimed responsibility for the Paris attacks, have bolstered the discourse of the National Front. It denounces Europe's open borders, what it calls the "migratory submersion" and what it claims is the corrupting influence of Islam on French civilization.