China's rulers ignore a fallen leader, 25 years after his death sparked tumult

Loading...

| Beijing

For clues about the future of democratic reform in China, read Tuesday’s “People’s Daily,” the official organ of the ruling Communist party.

Today marks 25 years since Hu Yaobang, an outspoken liberal and one of China’s most popular leaders, died in hospital after a heart attack. Social media networks are buzzing with admiring memorials to him. Yet the “People’s Daily” ignores the anniversary.

“The mood among reformers is definitely less optimistic and less confident” than it was a quarter of a century ago, says Zhang Jian, a professor of politics at Peking University. “We haven’t seen any serious reform in the last two years.”

Indeed, since President Xi Jinping took office a year ago he has overseen an unusually harsh crackdown on perceived opponents, jailing social activists and political dissidents for voicing even the most moderate criticism.

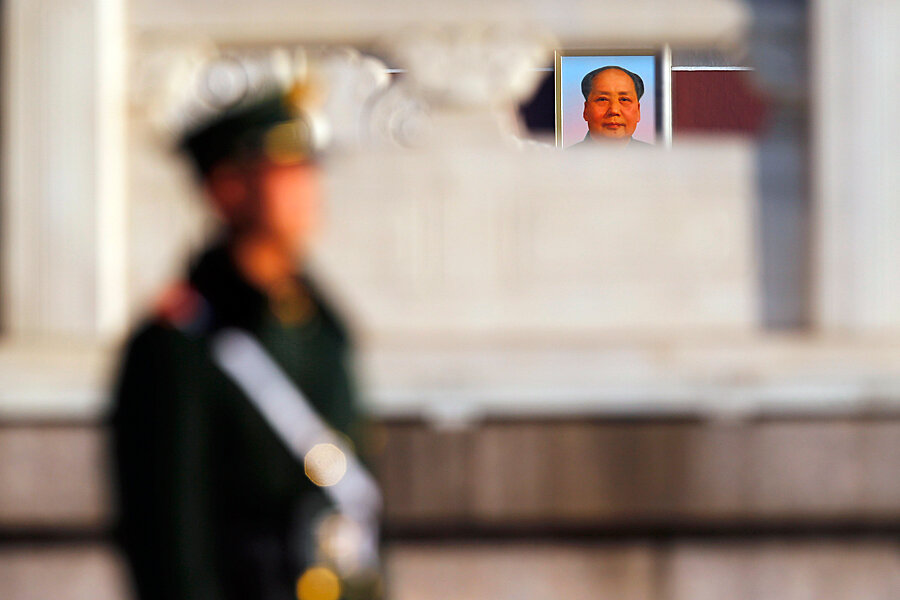

That wave of repression has made liberals nostalgic for the optimistic idealism that fired Chinese youth in the 1980s as Mr. Hu, the General Secretary of the Communist party, steered China away from the dogmatism of Mao Zedong’s rule.

It was Hu’s death that sparked the Tiananmen protests in 1989, as crowds of mourning students transformed into the mass demonstrations that ended on June 4 in a hail of gunfire. Political reform has been effectively stalled ever since.

One after another, Chinese leaders have made it plain that reformists’ dreams, such as press freedom or an independent judiciary, are not on the agenda. Mr. Xi has warned publicly that Chinese communists should not make the liberalizing mistakes of their former comrades in eastern Europe. In Beijing’s eyes, the Arab Spring offered further evidence of the dangers inherent in loosening the reins of political control.

Taboo nomenclature

Hu Yaobang’s name has been almost taboo for 25 years. Given how sensitive China's rulers are over the tumultuous events of 1989 and their subsequent scrubbing of history, this isn't surprising. The taboo remains in place not least “because [Hu] represented a trend of reform and democracy," says Wang Chong, an independent commentator.

Just last week, reports that former president Hu Jintao (no relation) had visited Hu Yaobang’s ancestral home were removed from Chinese websites by official censors.

But veteran liberals lament that they have more to contend with than a repressive government. Even more deadening, they say, is widespread public apathy.

“In the 1980’s people were quite idealistic,” recalls Dr. Wang. “The most challenging issue for China today is that there are no beliefs; nobody believes in Mao or Marx or Christianity or Buddhism. Most people in their twenties today do not care about politics.”

“Hu Yaobang represents a bygone age,” wrote Deng Long 2014 on Sina Weibo, a Twitter-like social media platform. “In those days people were poor but passionate.”

The personal isn't political

By contrast, says Li Chengpeng, a prominent social critic, “people today are more worried about protecting their own personal interests than about whether the country is heading in the right direction.”

Among those who are politically engaged, says Prof. Zhang, “more and more people are worried about the future and want the government to relaunch the sort of political reform that Hu Yaobang tried to do.”

The 370,000 people who posted memorial messages to Hu on Weibo, he argues, “reflect discontent about the delays and reversals of political reform.”

But many of those posting, he suggests, “are probably people in their 40’s commemorating their own youth. If it were a pop star’s birthday today, you’d have ten times that number of Weibo comments.”