For Beijing, Tibet threat is 'life and death'

Loading...

| Beijing

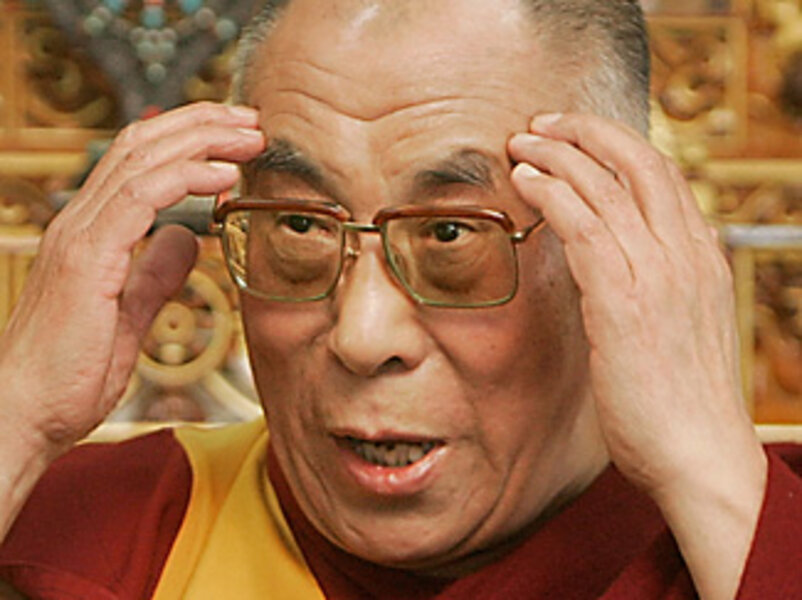

Nothing has emerged so clearly from the recent violence in Lhasa as the gulf between Western and Chinese views of Tibet and of exiled Tibetan leader, the Dalai Lama.

The saffron-clad monk, widely admired in the West as an icon of nonviolent struggle against the occupation of his homeland, was described Wednesday by a top Chinese official as "a wolf wrapped in monk's robes, a devil with a human face and a beast's heart."

The violence of that language, used by Tibet Communist party leader Zhang Qingli, indicates just how gravely Beijing views the challenge Tibetan unrest has posed to the government's authority.

"What other serious threat have Chinese governments faced ... that could be identified with a coherent movement and a single leader – and a charismatic one at that?" asks Robbie Barnett, a Tibet expert at Columbia University.

"We are in the midst of a fierce struggle involving blood and fire, a life-and-death struggle with the Dalai clique," Mr. Zhang warned his colleagues. "Leaders of the whole country must deeply understand the arduousness, complexity, and long-term nature of the struggle."

Chinese officials have offered just one explanation for the unrest in Lhasa: a plot by the Dalai Lama and his government in exile to further their alleged goal of breaking up China by winning Tibet's independence.

The Dalai Lama, who has repeatedly said that he seeks only autonomy under Chinese sovereignty, not independence, for his homeland, Tuesday condemned the violence in Lhasa and denied that he had played any role in it.

Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao, however, would have none of it. "We have plenty of evidence proving that this incident was organized, premeditated, masterminded, and inflicted by the Dalai clique," he told reporters Tuesday. "This has all the more revealed the consistent claims by the Dalai clique that they pursue not independence but peaceful dialogue are nothing but lies."

A problem of politics, not religion

Though Chinese President Hu Jintao has often praised the role of traditional Chinese religions such as Buddhism and Confucianism in contributing to a "harmonious society," Tibetan Buddhism poses a particular difficulty because its religious leader, the Dalai Lama, also plays a political role. "If this were only a matter of religion, it would be just a big headache," says Liu Junning, a political analyst in Beijing. "But the Dalai Lama has a very special role. This is political."

The Dalai Lama's moral status abroad "has made him an incredibly effective irritant in international affairs," says Professor Barnett. As a symbol for Tibetan protesters, "he could be shifting from an international irritant to a domestic threat."

Zhang's tirade appeared designed to strip the Tibetan leader of moral authority in the eyes of his people. Among his goals, Zhang claimed, was "to overthrow the leadership of the Communist Party of China … and restore the cruel slavery system of imperialism."

The Chinese authorities have chosen to heap all the blame for the recent troubles on the Dalai Lama's head, say some local and foreign analysts, because they have no other choice.

"This has a lot to do with China's long-term Tibetan policy, which they don't mention," says Mr. Liu. After more than 50 years of Chinese rule and economic aid, Tibetans are still restless enough to protest as they did last week.

The Tibetans have been eager to present themselves internationally as victims of last week's violence in Lhasa; exile groups have put the death toll at 99. But in challenging this version of events, the Chinese government has been reluctant to make too much use of video footage showing Tibetan youths beating Han Chinese to death and burning their shops, which would suggest that Chinese migrants were victims.

"That would be very sensitive," says Liu. "It would spread ethnic hatred." Beijing is anxious to present an image of ethnic harmony in Lhasa, despite widespread reports of Tibetan resentment at the rising tide of migrants from other parts of China.

Blaming the 'Dalai clique'

Indeed, the mainstream view in Beijing is that the Dalai Lama is responsible for provoking ethnic conflict. "Relations between the Han and [Muslim] Hui and Tibetans are very good," says Zhang Yun, a professor at the state-sponsored China Institute for Tibetan Studies.

"Maybe recently, some business disputes have broken out, but they are isolated incidents that the Dalai Lama seizes on ... to stir up hatred," he charges.

Nor do many Chinese Tibet experts accept claims by exile Tibetans, widely believed in the West, that last week's marches and riots illustrate broad dissatisfaction among Tibetans with Chinese rule. Among the rioters, says Professor Zhang, "were just a few local people who insist on Tibetan independence." The rest, he argues, were Dalai Lama loyalists who had returned from exile after studying abroad, and "others who don't want to work and got paid for being violent with the things they stole from stores."

"The Dalai clique maintained real-time contacts ... through varied channels with the rioters in Lhasa, and dictated instructions to his hard-core devotees and synchronized their moves," the official Xinhua news agency claimed in a commentary Tuesday.

Though officials from Prime Minister Wen downward have made much of the threat they see to China's territorial integrity from the Dalai Lama's activities, few scholars here share their fears.

"Tibet has been under Chinese control for seven centuries," says Zhang, presenting the Chinese account of Tibetan history. "Sometimes it was relatively tight, and sometimes relatively loose, but even when China was very poor and weak" in the early 20th century, "Tibet was never independent.

"Now our national power is very strong," Zhang adds. "So from both historical and practical perspectives, Tibetan independence is an impossibility."