'Mein Kampf' back in print. Informative or inflammatory?

Loading...

| Cologne, Germany; and Paris

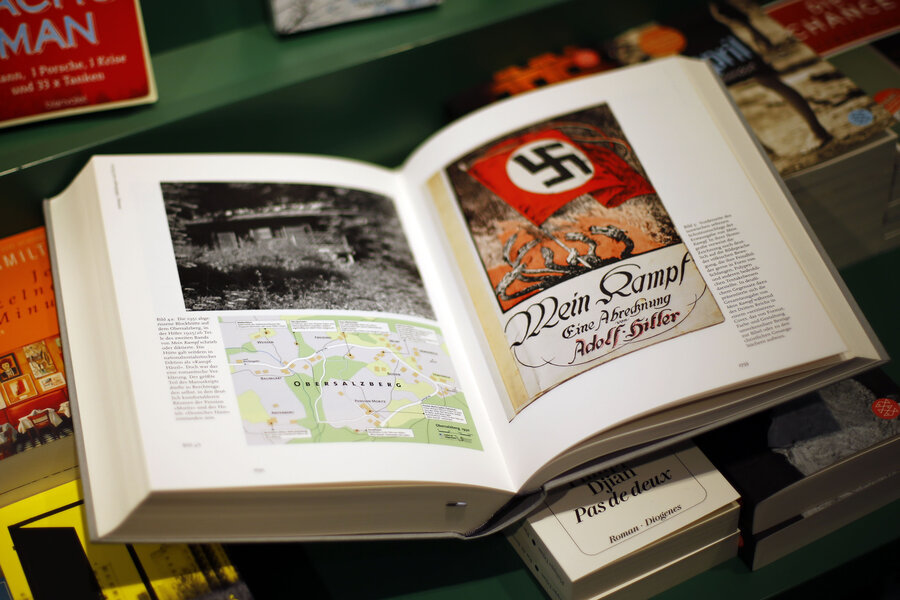

The decision to pick up an annotated copy of Mein Kampf, which hit German bookstores Friday for the first time since Hitler died 70 years ago, is not something Holger Wiess takes lightly.

As he flips through magazines at a bookstore in Cologne, the university student says he wouldn’t want anyone to think, for example, that he would be doing so out of contempt for the hundreds of thousands of refugees who have recently come to Germany.

But he plans on reading the 2,000-page annotated "Hitler, Mein Kampf: A Critical Edition" because he sees a chance to glean new insights. “You get a chance to learn more about that history, to understand it’s not the truth,” he says.

The expiration of the copyright on Mein Kampf – "My Struggle" – comes as France moved last week to declassify documents from its disgraced Vichy era of Nazi collaboration, and as reprints of Anne Frank’s "Diary of a Young Girl" stirred controversy. The French publisher Fayard has tentative plans to republish their own annotated version of Mein Kampf in 2018.

Some, especially Jewish groups, have voiced fear that these documents could not have re-emerged at a worse time, with the rise of nationalist and populist parties whose rhetoric has echoed some of the demagoguery of pre-war Europe. But many Europeans see the unearthing of documents and the fresh analysis as coming at exactly the right time.

“Allowing people to see the truth means they don’t feel like someone is hiding something from them,” says French historian Gilles Morin, who heads France’s association of users of national archives. “The extremist thinking already exists. They don’t need us to open up the archives to continue this type of thinking. … In the end, it’s better to publish than to hide.”

Mein Kampf, which was penned during Hitler’s stint in jail in Bavaria in the 1920s after a failed coup, reached millions of readers after the Nazis took power in 1933. After his death, the Allies handed the copyright to the state of Bavaria, which banned its republication. Now they no longer can, under European copyright law that stipulates that a work becomes part of public domain 70 years after the death of an author.

The majority of Germans – three out of five – aren’t worried about it stoking far-right flames, according to a recent survey by YouGov. More divided have been victims and survivors of the Third Reich, though Josef Schuster, the president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, has backed an annotated version for the purpose of “knowledge.”

The Institute of Contemporary History in Munich, which unveiled the new work today, has long argued that the copyright ban itself has done little to curb access to Nazi ideology. Old versions of Mein Kampf are available at many bookstores and online. “What is missing is a critical edition of this,” says Magnus Brechtken, deputy director of the institute.

He says the new edition has helped counter new threats to democracy. The government has relied on their testimony, he says, in an effort to outlaw the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) on the basis that it resembles rhetoric of National Socialism prior to 1945. “You can only prove this and show this if you take historic texts like Mein Kampf and analyze them, see where it comes from, what it means,” he says. “That gives you the opportunity as a democracy to fight against people that are openly attacking democracy.”

Not everyone is convinced. Henry, a bookstore customer in Cologne who gave only his first name, says that he was annoyed to hear that such a book could be published again. His uncle asked him to look for a copy for him and bring it on a visit. He refused, saying he didn’t want anything to do with “that psychopath.”

Such sensitivities have surfaced in France, too, which recently released 200,000 documents from the Vichy regime. Opening up the documents has brought back feelings of being conquered, much as the Germans are dealing with their legacy of having conquered.

“There is a feeling of fear in France that certain things will come out. There is a national embarrassment,” says Morin. “The memory of this war remains a burning issue.”

Still, there is a sense that with the passing of time, there is less risk of offending those who might have lived – or ruled – during the Vichy period. “The political class of today is so distanced from that post-war era,” says Annette Wieviorka, a French historian and Holocaust specialist. “The weight of this history isn’t as heavy as it was before.”

The access to Mein Kampf and Vichy documents comes as another copyright ownership ban is brewing – over whether Anne Frank or her father owns the rights to Anne Frank’s Diary. The Anne Frank Foundation set up by Otto Frank argues that he does, so it’s still protected. But Olivier Ertzscheid, a professor of digital culture at the University of Nantes in France who published the diary online Jan. 1, arguing that the copyright has expired, says that his battle mirrors that of those fighting to preserve and understand the legacy of the era.

“They take us back to the same period in history, and [opening them up to a wider public] is a testament to transparency and memory,” he says.