International adoption: A big fix brings dramatic decline

Loading...

When Silvia Sebac’s birth mother made the five-hour bus ride through the mountainous countryside to leave her at an orphanage in Guatemala City, the infant had every prospect of an international adoption – of captivating adoptive parents from the US or Europe.

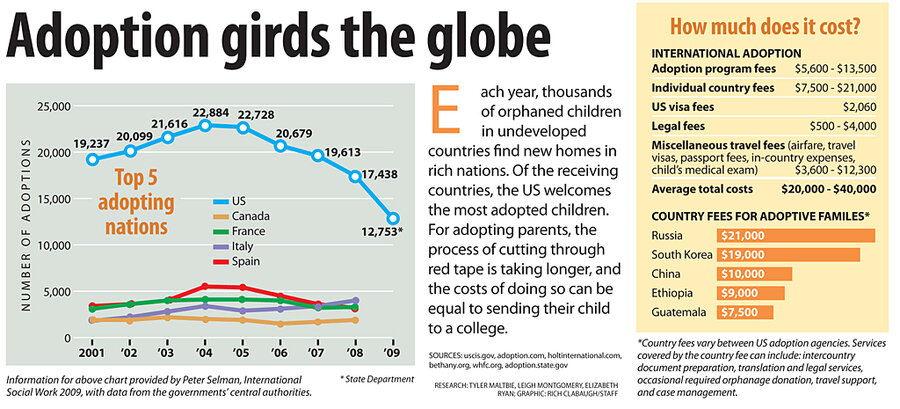

That was four years ago, when the adoption business was booming and people from rich countries were traveling the globe from China and South Korea to Russia and Ethiopia to find a child to complete their families. At the time Silvia arrived in Guatemala City, her country was giving up nearly 5,000 children annually – 1 in every 100 births. Adoption was an estimated $100 million industry that attracted thousands of international families willing to pay more than $30,000 to lawyers and agencies and to the capital city’s towering hotels that dedicated entire floors to adoptive parents, catering to their every diaper and baby cream need.

But by the time her two-year wait to be declared legally abandoned was up, dark-eyed Silvia had no takers. Intercountry adoptions had begun to plummet.

Once a secretive or shameful process in many countries, adoption – particularly the heartwarming gesture of rich people traveling to the ends of the earth for a baby – became iconic in modern culture. The likes of Madonna and Angelina Jolie adopting in Africa injected glamorous publicity as well as drew suspicion and cynicism to the process.

Along with the growth of international adoption came publicized scandal and consequently a chillier new adoption climate, with stricter government controls. It has caused the number of international adoptions to plummet, and left behind – if also protected – many orphans around the globe.

Silvia is one of them, prevented from joining a new family in what is considered the most adoptable period – the infant to toddler years. In the final days of 2007, with the system beset by allegations of baby theft and coercion of birth mothers, Guatemalan lawmakers placed a moratorium on international adoptions. It put in place a new system that

followed the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption, which is an international standard – and it implemented UNICEF-inspired policy dictating that a family within the country, preferably a relative, should be sought before international families.

Today when asked who her mother is, Silvia points to an orphanage caretaker, and says, beaming, “Mama Nico.” A slight, pretty girl, Silvia flashes four stubby fingers when asked her age: “Cuatro.”

And, says Alejandra Diaz, the director of the orphanage, “Hannah’s Hope,” Silvia is probably going to spend many more birthdays in the orphanage: “It is hard to say it, because I knew her when she was a baby, but she’s going to be here for years.” Ms. Diaz says her facility, which used to process 90 adoptions a year, now has 31 seemingly permanent orphan residents, and cannot afford to take in more of the estimated 4,000 Guatemalan children now backed up in state and private orphanages.

• • •

“We are in a period of adoption history where growing transparency is having a significant impact in various ways: Many of them are very good and some of them are very complicated,” observes Adam Pertman, author of “Adoption Nation” and the executive director of the Evan Donaldson Adoption Institute.

“Now that everyone’s watching, it’s incumbent on us to get it right – the short-term consequences clearly are leading to a decline in international adoptions,” Mr. Pertman adds. “But hopefully, if we really get it right now, the decline will be a blip, and more kids, not fewer, who need homes will wind up getting them, in their own countries or, if necessary, in others.”

As shown by the recent arrest of American missionaries in Haiti – accused of child trafficking for trying to take 33 Haitian children out of the quake-stricken country – the world’s intercountry adoption system needs to be fixed, agree children’s advocates and adoption agencies.

“Haiti magnified and amplified the issue that we deal with in over 180 countries,” says Susan Bissell, chief of child protection for UNICEF in New York. The earthquake – and the media attention that followed it – simply exposed the multitude of problems that many developing countries face and that drive the supply of orphans: extreme poverty among families, weak social welfare systems to find alternative family arrangements closer to home, and corrupt legal systems that operate on personal deals rather than legal principles.

Instead of finding families for every child in need, the present system is set up to find a child for every family that wants one. Navigating the unfamiliar and wildly varying rules of foreign courts has created a huge industry of adoption agencies and adoption-law specialists, who command large fees – often $20,000 to $40,000 per child. And while many adoption agencies do their work legitimately, the lure of such large fees has created powerful incentives for less legitimate agencies to procure children.

In Guatemala’s case, for example, “the government had lost control of the system,” says Marilys Barrientos de Estrada, a director of the governmental agency created to oversee the new adoption process. “It was purely in the hands of the lawyers and agencies. And it wasn’t about the children, it was about the money.”

To ensure that a child’s interests are put first, the 1993 Hague Adoption Convention gave countries a legal blueprint to help them make adoption a transparent, predictable, and legitimate process. As implementation of the treaty by the United States and 81 other countries progressed over the past few years, the number of intercountry adoptions dropped dramatically.

“The intention of the Hague convention is not to slow down adoptions,” says William Duncan, deputy secretary-general of the Hague Conference on Private International Law, which oversees implementation of the Hague Adoption Convention. “In the last few years, the number of adoptions has tended to drop, but my impression is that has to do with a lot of specific conditions in specific countries.”

The new rules of adoption combined with fewer available children have caused the slowdown, says Pertman. The Hague convention “caused a real shake-up” because a lot of social agencies in developing countries simply can’t comply. And scandals in Guatemala and Romania, and China’s rethink of its pro-adoption policies, dramatically reduced the supply of adoptable children. The result, he says, is “a very long wait period.”

Guatemala’s scandals resulted in the moratorium on international adoption. Likewise, while Haiti deals with the postquake tsunami of international requests to adopt orphaned children, and as it processes the case of the arrested missionaries, it has become acutely aware of the weakness of its documentation process. (“If a child isn’t registered, the child doesn’t exist,” says Jennifer Bakody, UNICEF communications officer in Haiti. “Then there’s no way to protect the child, he/she is really lost from the system.” And that’s how good intentions can turn into scandal.)

So the Haitian government has announced a shutdown of all adoptions, partly out of caution but partly out of necessity – its main adoption judge was killed in the quake and government documents have been lost in the chaos. But international adoption officials in Port-au-Prince report that irregularities continue in the chaos: The Haitian government declared that adoptions in process could only be signed off by the prime minister, but it’s clear that some adoptions continue with other ministers signing off.

International authorities are encouraging Haiti not to attempt adoptions at the moment. A country like Haiti needs to rebuild before it gets into the business of helping find individual homes for adoptable children, Ms. Bissell argues.

And once it can focus on adoption again, Haiti’s priority should be less international adoption than sorting through the chaos that may reveal many so-called orphans do have family. One complication unique to Haiti, say observers, is its informal “gifting” of children to better-off families with the hope the child’s lot will improve and the child will be better cared for (sometimes it has been called a form of slavery). This restavek system (from the French rest avec, rest with), broke down in the earthquake, says Carol Bakker, UNICEF subregional adviser for child protection, and hosts are leaving these children behind. Adoption authorities are trying to register them so that they can be returned to families, placed in interim care, or – as a last resort – put up for international adoption.

“Ideally,” says Donald Moore, the US general consul in Port-au-Prince, “the government has to vet the best solution for every child. In most countries, adoption is not the first solution. You want to reestablish the child on the ground before you look for external solutions.”

• • •

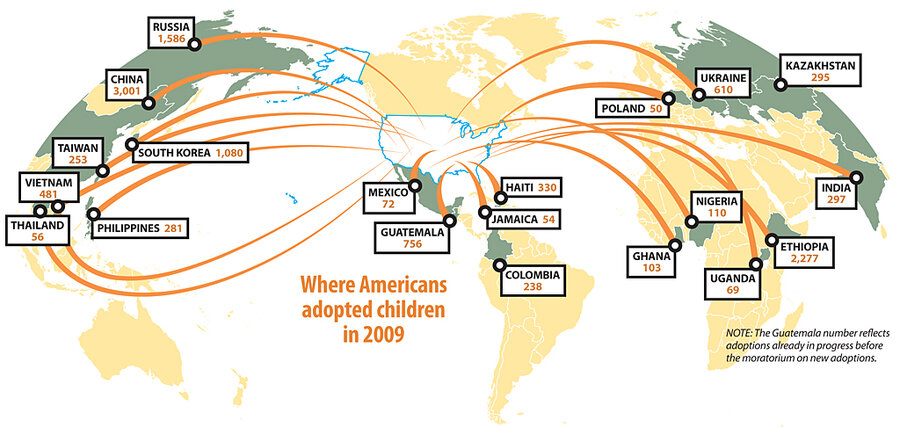

China, Russia, and Guatemala have been, until recently, the biggest source countries for adoptable children. But each for its own reasons has drastically reduced the number of children available for international adoption.

In China, the number of children sent abroad plummeted from 14,500 in 2005 to 5,942 in 2008, according to figures collected for UNICEF by Peter Selman, an adoption expert at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, in England.

Great changes in social and economic policies, say experts, have affected the availability of children for international adoption.

In the past, the one-child policy – blamed for the current demographic bulge of boys, which have been seen as more valuable than girls – caused an influx of unwanted, healthy Chinese girls to orphanages.

Today, few healthy Chinese girls are put up for adoption, and the decline is driven by adjustments in the one-child policy – including encouragement of domestic adoption and, in some regions, of higher birthrates – and an increase in prosperity that have made parents more likely to keep a girl.

In 2008, the number of domestic adoptions, according to official Chinese statistics, had grown to more than 37,000 annually. There is high demand in China and the US to adopt, says Kay Johnson, an expert on domestic Chinese adoptions at Hampshire College in Amherst, Mass. “The bottom line is that the supply of healthy babies [in China] is down,” she says.

So nearly 50 percent of Chinese children adopted by US parents have special needs, such as congenital heart defects, cleft palates, and clubfeet, explains Chuck Johnson, chief operating officer at the National Council for Adoption, in Alexandria, Va. Half of these special-needs adoption cases come through a Chinese government-designed program called the Waiting Child Program, which seeks to find outstanding families for children diagnosed with special medical needs.

“Make no mistake, those of us who have been in this field for a long time knew that there would be a day like this, and it has happened,” says Melody Zhang, associate director of Children’s Hope International, an organization that has helped more than 100,000 Chinese children find homes with US families. Ultimately, it’s a good thing, she says, because more children – healthy or not – are being placed.

• • •

The shift in adoption trends is felt nowhere more than at Detksi Dom No. 1 – Children’s House No. 1 – in the Moscow suburb of Vikhino. About 60 children, ages 3 to 7, call the squat concrete orphanage beneath towering apartment blocks home.

Though many from this orphanage were adopted in the past by European or American families, now almost all who are adopted from this facility are claimed by Russian parents and taken to new homes inside their own country.

The dramatic change is captured best in national statistics: In 2004, foreigners adopted 9,400 Russian children, and Russian citizens adopted 7,000, according to the Ministry of Education and Science.

By 2008, only 1,198 Russian children were given to foreigners for adoption, and Russian citizens adopted 7,683. Also, more than 100,000 Russian children were placed in temporary foster homes in Russia.

One of the main reasons for the dramatic change is that Russian lawmakers have made a concerted effort to put domestic adoptions first.

“Adoption to another country will be considered as an alternative only if the child cannot be transferred to a family in [the] country of his origin,” a spokeswoman for the Education Ministry said in a written response to questions.

And the government now pays families a bonus of $1,000 for taking in a foster child, with generous monthly payments for upkeep. Under a program started by former President Vladimir Putin in 2006, women can now receive up to $10,000 for bearing – or adopting – a second child.

In the recent past, a historic Russian reluctance to adopt children stood in irony alongside nationalist rhetoric against the idea of “selling Russian children abroad.” But both attitudes have largely disappeared, experts say.

“Russians were reluctant to adopt in the past, and the system of foster homes was completely undeveloped in this country. But that’s turned around amazingly in the past few years,” says Natalia Serova, director of Detski Dom No. 1.

Even five years ago, says Yekaterina Bridge, Moscow representative of World Association for Children and Parents (WACAP), “the average Russian thought foreign adoption was all about black-marketing Russian kids. But the Russian media has stopped publishing scare stories like that, and we find the social attitude about international adoptions is now much calmer and more positive.”

Some Russian celebrities, such as the TV presenter Svetlana Sorokina (Russia’s version of Katie Couric), have adopted in recent years. Ms. Sorokina wrote a very compelling account, with photos, in a popular magazine in which she detailed her personal search, her bureaucratic ordeal, and her profound feelings of happiness when she eventually brought her child home.

Also, there’s a middle class in Russia now that didn’t exist before, and it includes middle-aged professionals with means and stable lives who want to have more children in their homes. Further, philanthropic notions – such as individual helping and giving to the less fortunate – have also grown, particularly within that same class of Russians.

Russia’s Ministry of Education and Science says there are about 760,000 orphans in Russia (out of a population of 27 million children), but only 140,000 of them are listed in the huge official database as available for adoption. About 70 adoption agencies from a dozen countries still work in Russia, despite a severe shakeout three years ago that saw all international adoptions frozen and many agencies stripped of their accreditation.

With new rules governing adoptions, an American couple hoping to adopt a Russian child may expect the process to take two or three years and to be very costly.

Despite all the red tape, Russia is far from the worst country in which to work in the former Soviet region, says Ms. Bridge. “The Russian system actually cuts some of the corruption that is very prevalent [elsewhere],” she says. “In Russia, there are very clear written rules, so there’s no ambiguity about what’s required. It’s that ambiguity in other places that opens the door to corruption.”

• • •

Once the world's second-largest source for adopted children, Guatemala is set to open itself to international adoptions again this year. It received letters of interest from 10 countries – including the US, France, Spain, and Denmark – that want their residents to be able to adopt from Guatemala, says Rudy Zepeda, spokesman for the National Adoption Council, the new government agency. Once the pilot program starts, in June or July, only 60 Guatemalan children will be made available to international families. After that, intercountry adoption will still be limited to 100 or 150 cases, mostly older children like Silvia or those with disabilities.

The estimated 4,000 other children now living in orphanages will have to first be declared “adoptable” by Guatemalan courts and then be made available to Guatemalan families. As of mid-February, after more than two years under the new system, 590 Guatemalan families had applied to adopt a child and the courts had cleared 559 children, but just 253 of those children had been adopted.

Meanwhile, children like Silvia wait, growing up in homes that try to replicate family life. “We can give them love, we can give them clothes, and feed them,” says Diaz, the orphanage director, “but it’s not the same as sitting down for a meal with your family.”