Why the Grand Mufti's fatwa gambit is unlikely to checkmate chess

Loading...

Over the centuries, dozens of religious and political leaders have tried to put chess in a corner, but experts say a fatwa by Saudi Arabia’s leading cleric against the game is an ineffective move.

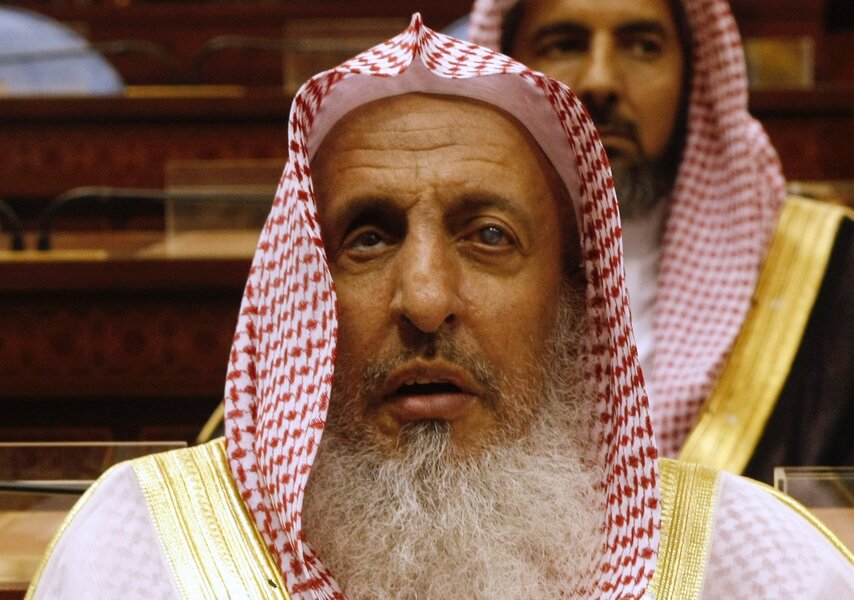

While the rest of the world has come a long way from the year 1061, when Roman Catholic Cardinal Petrus Damiani (1007-1072) banned the clergy from playing chess, Grand Mufti Sheikh Abdulaziz Al-Sheikh is willing to turn back the chess clock this week by issuing a new fatwa, or religious advisory, on a Saudi television show.

The Grand Mufti referred to the game as “the work of Satan,” and akin to alcohol and gambling in the eyes of Allah.

Throughout history, chess has been banned on political, social, and religious grounds, according to Chess.com. In the 14th century, Charles V (1337-1380) banned chess in France. In the 1920s, public chess playing on Sundays was banned in Massachusetts. In July 1933, all Jews were banned from the Greater German Chess Association.

In the late 1950s, the Soviets banned chess in Antarctica after a scientist at one of their research stations killed his colleague with an axe after he lost a game of chess. In 1966, chess was banned in China as part of the Cultural Revolution. In 1994, chess was banned in Afghanistan by Taliban edicts – anyone caught playing chess was beaten or imprisoned. In 2010, New York City banned adults from playing chess at Emerson Playground.

In response to this latest gambit to ban the game, chess fans and Grandmasters alike took immediate issue with the fatwa on social media.

Grandmaster Susan Polgar, head coach of Webster University's top-ranked chess team in the nation, says in an interview, “I absolutely disagree with these pronouncements on chess. There is no gambling element in chess. Chess is purely an intellectual game which requires skill and knowledge, and it can help countless young people develop analytical, concentration, calculation, decision making, and problem solving skills, etc.”

Meanwhile, religious and cultural scholars say there is no cause for alarm since a fatwa is more of a guideline than a directive.

“What most people don’t understand about a fatwa is that it’s an opinion and it’s not binding,” says Imad-ad-Dean Ahmad, president and director of The Minaret of Freedom Institute in Maryland, in an interview. “I don’t personally know any American Muslim who will stop playing chess because of this announcement, but that doesn’t mean they don’t exist.”

The origins of this fatwa come from some of the scholars interpreting chess as a form of gambling, Dr. Ahmad says.

“Exactly why they would [see it as gambling] is unclear. One could bet on chess, I suppose, but it has already been dealt with in Saudi Arabia with regards to horse racing and the King’s Cup,” he says.

Ahmad says the issue of chess being “forbidden” in the Arab world comes from a hadith, which is the term given to any report or narrative claiming to quote what the prophet Muhammad said verbatim on any matter.

“So, the hadith on chess claims that someone was playing a game and the game is named in Arabic and they say that the prophet had seen this game and he said ‘He whose hands have touched this game would burn in hell,’ ” says Ahmad. “They understand this game that is described as being chess. However, I’m not so sure it could have been chess because chess was introduced into the Muslim world through Persia [modern-day Iran] and I don’t know if it could have gotten to him yet. Travelers and merchants to Persia could have brought back a set.”

According to scholarly works, the prophet Muḥammad was born in the year 570. The game of chess has multiple origin stories which variously claim its inception as being in either 6th century India or 5th century Iran.

"It is possible that the game the prophet Muhammad was talking about was chess," David Shenk, author of "The Immortal Game," says in an interview. "But in all my years researching it, I never came across any research indicating Muhammad had ever played or encountered chess. If I had, it would be in my book. That said, it's not impossible that he ran across it a some point."

"It's an incredible irony here because chess is a game of the intellect and that was consistent some of the core ideas of how Islam began. Islam was designed to be intellectual as well as religious and chess was the emblem of that," Shenk says. "The pieces themselves were aesthetically reshaped into abstract pieces there. There is just all kinds of history of Muslims playing chess vigorously and taking it wherever they went."

“Chess is one of the oldest games and by far the most popular on this planet,” adds Mr. Polgar. “Chess is extremely inexpensive to play and chess also promotes unity, diversity, understanding, and peace. In fact, I led the charge along with former world champion Anatoly Karpov and former Russian President Mikhail Gorbachev in the global initiative Chess For Peace more than 10 years ago.”