Good Reads: On liberal Christians, political Islam, and the news profession

Loading...

Where are the liberal Christians?

If you look at the American political environment over the past decade or two, you’d think that the only room for Christian activists was to be found on the right side of the political spectrum. That’s because the religious movement making the most noise in American politics is that of Christian conservatives, arguing for heterosexual marriage and against birth control and taxation. Liberal Christians exist, to be sure, but their voice is muted.

It wasn’t always like this, writes John Stoehr, a Yale political scientist, in a well-researched opinion piece for Al Jazeera’s English website. He argues that just as liberal Christians like William Jennings Bryant led the charge against growing corporate control in the early 20th century, they should also “fight fire with fire,” and reclaim the proud position that liberal Christians held in more recent fights such as the American civil rights movement.

“[L]iberals are supposed to be the voice of reason, pragmatism and enlightenment.... Liberalism, as the late Daniel Bell suggested, is the ideology of no ideology. It is the practical application of technical knowledge to situations in need of repair.”

How democracy may shape 'Political Islam'

Those Americans who are proud of the prominent role that religion has in shaping politics here often find it terribly creepy and dangerous when it happens in other societies.

Consider the rise of Islamist parties such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt following the Arab Spring movement that brought down President Hosni Mubarak. The Brotherhood is most decidedly conservative, and in its early days it was prone to violence; some worry that the wave of attacks on Egyptian Christians and other minorities is a presage of future repression if they come to power.

But Olivier Roy, a professor at the European University Institute, argues in a piece excerpted on Foreign Policy’s website, that the Islamists – while they may not have embraced the liberal democratic spirit of the Tahrir Square protests – may need to adjust their methods and mind-set to suit the times.

“The development of both political Islam and democracy now appears to go hand-in-hand, albeit not at the same pace. The new political scene is transforming the Islamists as much as the Islamists are transforming the political scene.”

Extremist views on trial act as repellent

Islamists, of course, are the bogeymen of the early 21st century, and just as some Americans warn of “creeping sharia” or accommodation of Muslim citizens in a diverse American society, there are right-wing factions in Europe that warn of the same thing.

If Anders Behring Breivik, the Norwegian right-winger who is on trial for killing more than 70 people to make a statement against what he saw as the Islamicization of Norwegian society, intended for his trial to be a showcase for his weird and hateful ideas, he seems to be alienating the very people he had hoped to attract.

The Atlantic magazine’s Max Fisher says it’s possible that a trial of America’s own political demon, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the accused “mastermind of the Sept. 11 attacks,” might have had the same effect on young disenfranchised Muslims, if the American civilian court system had been given the chance to operate.

“KSM and Osama bin Laden’s violence ended up alienating Muslims not just from al-Qaeda but from radical Islamist movements more broadly. Breivik’s violence seems to have alienated immigrant-weary white Europeans – his intended audience – from the far-right movements of which he was a fringe loner. His trial is exacerbating that trend; wouldn’t KSM’s trial have done the same?”

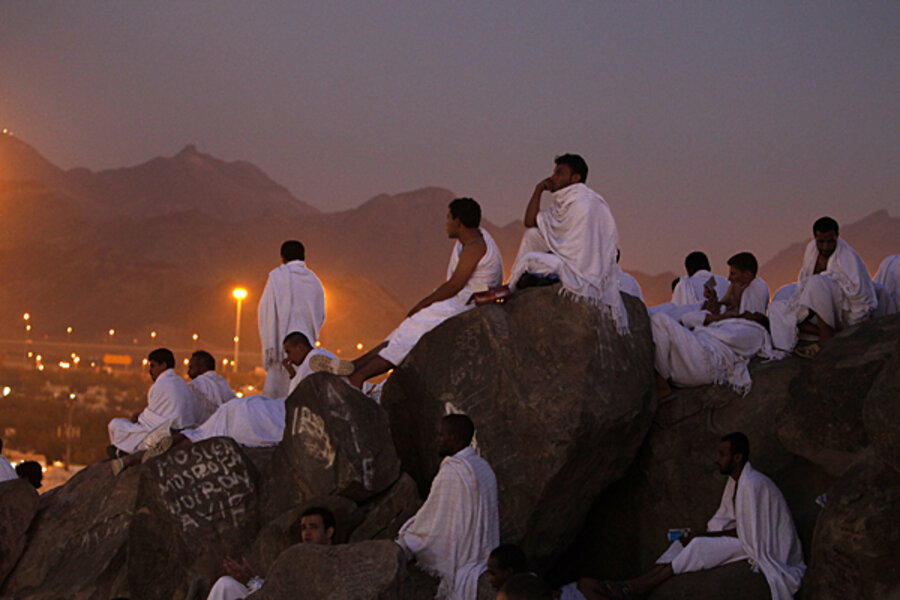

A novelist's tour of the Hajj

As a non-Muslim, I will never experience firsthand the Islamic pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca. I see two possible solutions here: (a) convert to Islam, or (b) read novelist Basharat Peer’s account of his own pilgrimage in The New Yorker. Mr. Peer touches lightly on Islam itself, but tells a brief history about the Saudi kingdom that hosts the hajj. While many other societies with holy sites do their utmost to preserve a sense of the ancient, Saudi Arabia aspires to create and keep creating an entirely modern city in which to host the nearly 1,400-year-old pilgrimage.

Why journalism still rocks

Finally, amid all the bad news about the demise of journalism, now we have a survey that finds journalism to be one of the world’s worst jobs, after waiting tables. But while the pay is lousy, the hours are long, and the industry seems to be in an unending tailspin, Forbes staff writer Jeff Bercovici writes this week that it’s still the Best. Job. Ever. Reason No. 1: Journalism is like college.

“You’re always building new mental muscles. You start out on a new beat or a new story as ignorant as a child, and within a few weeks or months you’re an expert. Wait, you didn’t like college? Don’t be a journalist. Problem solved.”

Unsurprisingly, I find his arguments persuasive.