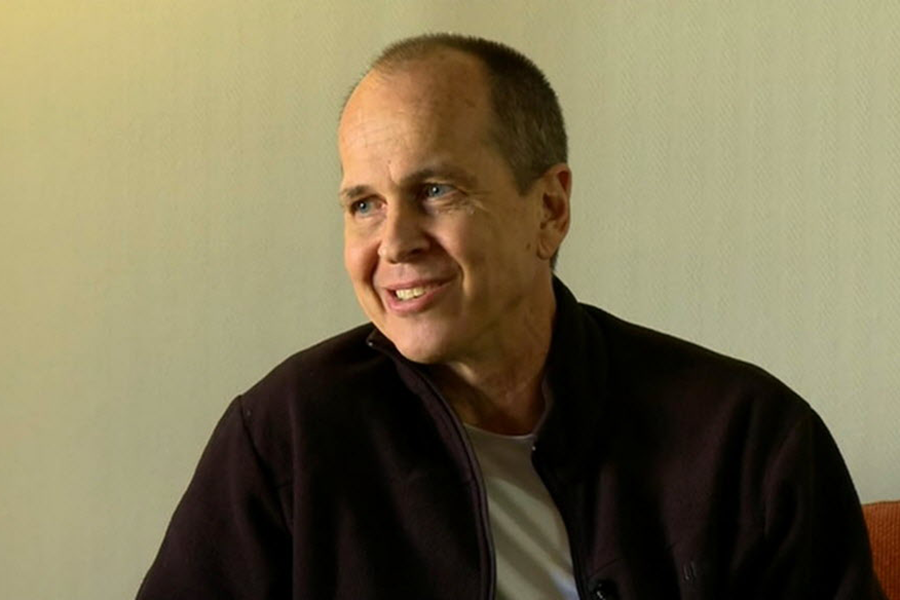

Al-Jazeera reporter Greste has mixed feelings after release, colleagues remain jailed in Egypt

Loading...

| CAIRO

Al-Jazeera journalist Peter Greste expressed "relief and excitement" Monday at being freed after more than a year in an Egyptian prison, but also said he felt real stress over leaving his two jailed colleagues behind.

His first public comments came as a court in Egypt sentenced 183 people to death in the violence following the 2013 ouster of former President Mohammed Morsi in the latest in a series of harsh punishments that have drawn condemnation at home and abroad.

Greste, an Australian, told Al-Jazeera English he experienced a "real mix of emotions" when he was freed Sunday because fellow journalists Mohamed Fahmy, an Egyptian Canadian, and Baher Mohammed, an Egyptian, remained imprisoned on terrorism charges and for spreading false information. The three were arrested in December 2013 and received sentences of seven to 10 years before their convictions were overturned on appeal. A retrial began Jan. 1.

Later Monday, Canadian Foreign Minister John Baird, said Fahmy's release was imminent but provided no time frame. Fahmy's family said authorities required that he give up his Egyptian citizenship as a condition for his release.

Authorities presented no concrete evidence to back the charges against them. They insisted they were doing their jobs and are widely seen as having been caught up in a quarrel between Egypt and Qatar, which funds Al-Jazeera and was a strong backer of Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood.

"It was a very difficult moment walking out of that prison, saying goodbye to the guys, not knowing how much longer they all have to put up with this," said the 49-year-old Greste.

He also spoke of how he spent his 400 days of incarceration.

"The key is to stay fit physically, mentally and spiritually," he said, explaining that he followed a workout regimen, running in a limited space, but also studied and meditated.

"I made a very conscious effort to deal with all three things and dealing with each day as it came," Greste said.

Because of an "awful lot of false starts," he said he had remained unsure he would really be free until he was seated on the EgyptAir flight that took him to Cyprus.

"Freedom was close, if not imminent, only to have it snatched away," he said of the previous times he thought he was being released.

Greste called his release a "real rebirth," adding that he was looking forward to watching a "few sunsets" and gazing at the stars, as well as spending time with his family.

"It is those little beautiful moments of life that are really precious ... that is what matters, not the big issues," he said.

Prison officials and Egypt's official Middle East News Agency said Greste's release resulted from a "presidential approval" and was coordinated with the Australian Embassy.

There has been no word on the fate of his two colleagues, Fahmy and Mohammed. While Fahmy is expected to be deported to Canada when released, it is not immediately clear what will happen to Mohammed, an Egyptian citizen.

President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, in office since June, has said repeatedly that he would not have allowed the case to go to trial if he was president at the time of their arrest.

In his interview, Greste appeared at pains not to criticize el-Sissi's government or the Egyptian judiciary. While his release was a "big step forward" for Egypt, he said, Cairo needs to free Fahmy, Mohammed and several other Egyptian journalists convicted in the same case.

U.S. State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki welcomed Greste's release and urged Egypt to "follow this positive step with measures to address the verdicts against detained journalists and peaceful civil society activists."

"Freedom of the press, protection of civil society and upholding the rule of law are crucial to Egypt's long-term stability and prosperity," she told reporters in Washington.

U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon welcomed Greste's release and said he hoped that other journalists in Egypt would soon be freed as well, according to a statement by his spokesman.

Greste had only been in Egypt for a few weeks when he was detained. Fahmy had taken up his post as an acting bureau chief for Al-Jazeera English in Cairo only a couple of months before his arrest.

After freelancing in Britain, Greste joined the BBC as its Afghanistan correspondent in 1995. The following year, he covered Yugoslavia for Reuters before returning to the BBC. He spent more than a decade with the British broadcaster, reporting from across Latin America, the Middle East and Africa before joining Al-Jazeera in 2011 — the year he won a Peabody Award for a BBC report on Somalia.

Judge Mohammed Nagi Shehata, who convicted the Al-Jazeera journalists, is the same one who sentenced the 183 Egyptians to death.

That case involved the ransacking of a police station in a village just outside Cairo and the torture and killing of 15 policemen and mutilation of some of their bodies. It was believed to be a revenge attack by Morsi loyalists for the government's crackdown on the Brotherhood.

Psaki said the U.S. was "deeply concerned" by the mass death sentences.

"It simply seems impossible that a fair review of evidence and testimony could be achieved through mass trials," she said. "We continue to call on the government of Egypt to ensure due process for the accused on the merits of individual cases for all Egyptians, and discontinue the practice of mass trial."

Shehata has developed a reputation for harsh sentences against perceived government critics. He has also sentenced three prominent revolutionary activists to prison for violating a new law barring street protests without government permission.

He is also known to deal harshly with lawyers who defend activists, referring at least two of them to prosecutors to question them over perceived courtroom breaches.

Other judges also have handed down mass death sentences against Brotherhood supporters, including more than 1,000 in two mass trials that were heavily criticized by international human rights groups. Many of those sentences were later overturned on appeal, and in one of them, a judge was removed.

The military ousted Morsi in July 2013 after a year in office amid huge protests of his rule. His supporters staged two large public sit-ins in Cairo, which were broken up by police on Aug. 14, 2013, with hundreds killed. The attack on the police station in the village of Kerdassah began a few hours after the pro-Morsi sites were cleared.

The Muslim Brotherhood has been declared a terrorist organization by the Egyptian government.

Morsi faces multiple trials on charges that include conspiring with foreign groups and authorizing the killing of protesters. He is scheduled to begin a new trial Feb. 15 on charges connected to leaking classified national security documents to a foreign country.

___