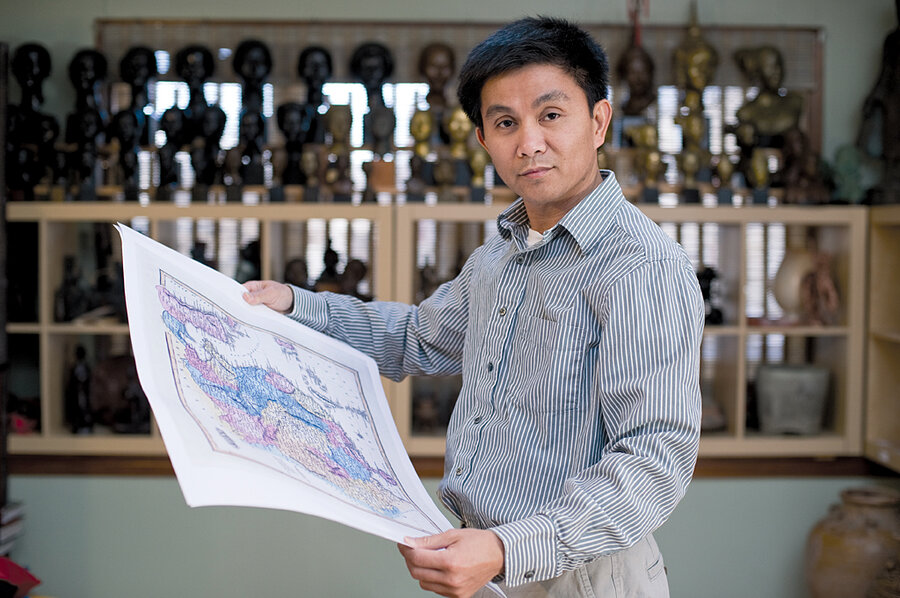

Thang Dinh Tran loves maps and Vietnam. That may put him in the eye of a storm.

Loading...

| West Hartford, Conn.

In 1995 Thang Dinh Tran invited an expert on traditional Vietnamese music to give a talk at the University of Connecticut (UConn). That summer, the distinguished Tran Van Khe, who taught at the Sorbonne University in Paris, visited the UConn campus.

His talk became part of UConn history. It drew an audience of more than 300, but one-third of them were protesters against Vietnam's communist government.

"They thought I invited a figure from Vietnam to propagandize communism," recalls Mr. Tran, who then was a third-year mechanical engineering student and served as chairman of the Vietnamese Student Association.

The situation calmed down only when the school confirmed that the Vietnamese professor lived in Paris, not Vietnam, and that his talk was about music, not communism.

The incident didn't discourage Tran. Instead, he realized meeting with a Vietnamese cultural icon had aroused his love for his home country. "[Professor Khe's] talks gave me inner strength to pursue cultural exchanges," says Tran, who's gone on to host talks on Vietnam at other Connecticut universities, found a Vietnamese magazine, and help Vietnamese students come to the United States to study.

Now his passion for all things Vietnamese has combined with another passion: collecting old maps. Together they have placed him at the center of a territorial dispute between Vietnam and China.

Tran, who is single, lives with his parents in the West Hartford, Conn., house they moved into after coming to the US. He works at Pratt & Whitney, an aerospace manufacturer.

Last summer, Tran expanded his passion for Vietnamese antiquities into a new area. It drew little interest from fellow collectors, but it made headlines in Vietnam.

Tran has collected 150 ancient Chinese maps and three ancient atlases that indicate that the Paracel and Spratly Islands in the South China Sea have never been part of China, as it has long claimed, but instead belong to Vietnam.

The Paracel and Spratly Islands (known as Xisha and Nansha in Chinese, and Hoang Sa and Truong Sa in Vietnamese) are now at the center of a diplomatic row between the two Asian neighbors; both have claimed the potentially oil-rich region.

Experts on the South China Sea say that if the dispute over the islands were taken to the International Court of Justice, Tran's map collection might be used as historical evidence to disprove China's claim.

"As a Vietnamese, I have the obligation to preserve my country," says Tran, who adds that he often finds his inspirations turning into actions "no matter day or night."

Tran arrived in America with his parents in 1991 under a humanitarian program established between Hanoi and Washington that allowed former Vietnamese political detainees to immigrate to the US.

After settling in West Hartford, Tran continued his studies in mechanical engineering at UConn. He received a second degree in management and engineering before working first for Electric Boat and then Pratt & Whitney.

One evening last July, Tran checked the news from Vietnam. His eyes landed on a headline that read "Ancient map proves Vietnam's sovereignty over Paracel and Spratly Islands."

He devoured the story. An idea flashed through his mind. He turned to eBay and typed in terms such as "Chinese maps," "Indies maps," and "Hainan Island."

"The story that a researcher in Vietnam found and donated a 1904 Chinese map drawn by the Chinese under the Qing regime from the 18th to 19th century inspired me to search for Chinese maps published by Western countries," Tran says. "Western people's works are often based on scientific grounds, so I think ancient maps they depicted could be scientific evidence to prove Vietnam's sovereignty."

Since that summer evening, Tran has continued his online search, called historians, and consulted South China Sea experts from the US to Vietnam. His collection eventually grew to total 150 maps and three atlases. They were published in England, the US, France, Germany, Canada, Scotland, Australia, India, and China from 1626 to 1980.

"Some 80 maps and three atlases indicate the frontier of southern China is Hainan Island, and 50 maps indicate the Paracel and Spratly Islands belong to Vietnam," Tran says.

"Thang's findings provide us with more scientific and historical evidence to prove Vietnam's sovereignty over Hoang Sa and Truong Sa, and refute China's groundless claim over these two islands," says Dr. Tran Duc Anh Son, deputy head of the Da Nang Institute for Socio-Economic Development, a think tank on the Paracel and Spratly Islands in Vietnam.

Tran's collection shows contradictions to China's claim to "indisputable sovereignty" over the islands, adds Carl Thayer, a professor emeritus at the University of New South Wales in Australia and an expert on the South China Sea.

Tran's map project sets a capstone on his years of effort to foster cross-cultural awareness between the US and Vietnam.

Together with friends in 1996 he started a Vietnamese magazine to promote awareness of Vietnam's culture called Nhip Song (Rhythm of Life). The 124-page annual features Vietnamese history, society, literature, and art, and draws on the expertise of many Vietnamese scholars and artists in the US, Vietnam, and elsewhere.

By taking a neutral position on Vietnam's communist government, which has established friendly relations with the US in recent years, Tran's magazine reaches out to Vietnamese-Americans of all political positions.

In 2000 Tran brought his cultural exchanges to a new level. Backed by several high-profile overseas Vietnamese scholars, including Khe, he founded the Institute for Vietnamese Culture & Education (IVCE). Besides presenting cultural programs, his nonprofit group travels to Vietnam to offer workshops on how to participate in student exchanges in the US and assistance with exchange program applications.

"We believe students who have the opportunity to study abroad will bring back with them ideas and concepts from American universities that can contribute to the development of Vietnam," says Tran, who still serves as president of IVCE.

For the past 12 years, Tran has shuttled between the US and Vietnam, holding about 60 summer workshops on "studying in America" with help from hundreds of Vietnamese-Americans, who offer guidance based on their firsthand experiences. Dozens of Vietnamese and US universities have now partnered with IVCE to exchange delegations and establish cooperative programs.

At the same time, IVCE has presented 44 events across the US, introducing audiences to Vietnamese classical music, folk art, painting, literature, documentaries, and feature films.

Over time, those who once opposed Tran's work as propaganda for a communist government have changed their minds. "They love me now," says Tran while on his way to Washington to prepare for a screening of five short documentaries by young Vietnamese filmmakers.

Tran appreciates his life in the US and the career opportunities it has afforded. "America is my second country," he says.

"He lives in America, but his heart is in Vietnam," says Hong Anh, a movie star and film producer in Vietnam who joined Tran in November 2012 to tour American universities in the Northeast.

Tran says he is glad that last November he donated his map collection on the Paracel and Spratly Islands to the Da Nang Institute for Socio-Economic Development. "No one forced me, but I feel the obligation to work for my country," he says. "It's a mission in my life."

"Tran has been devoted to many programs benefiting Vietnam in different ways," says Professor Khe, who has become his mentor. "But he never boasts about what he's done."

Helping in Asia

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations worldwide. Projects are vetted by Universal Giving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

Here are three groups selected by UniversalGiving that work in Asia:

• The Global Volunteer Network Foundation aids the charitable and educational work of community organizations around the world. Project: Volunteer at an orphanage in Vietnam.

• Asia America Initiative builds peace, social justice, and economies in impoverished communities. Project: Donate to peace caravans that build understanding across cultures.

• Greenheart Travel is a nonprofit cultural exchange organization promoting understanding, environmental consciousness, and peace. Project: Volunteer in a classroom in Vietnam.