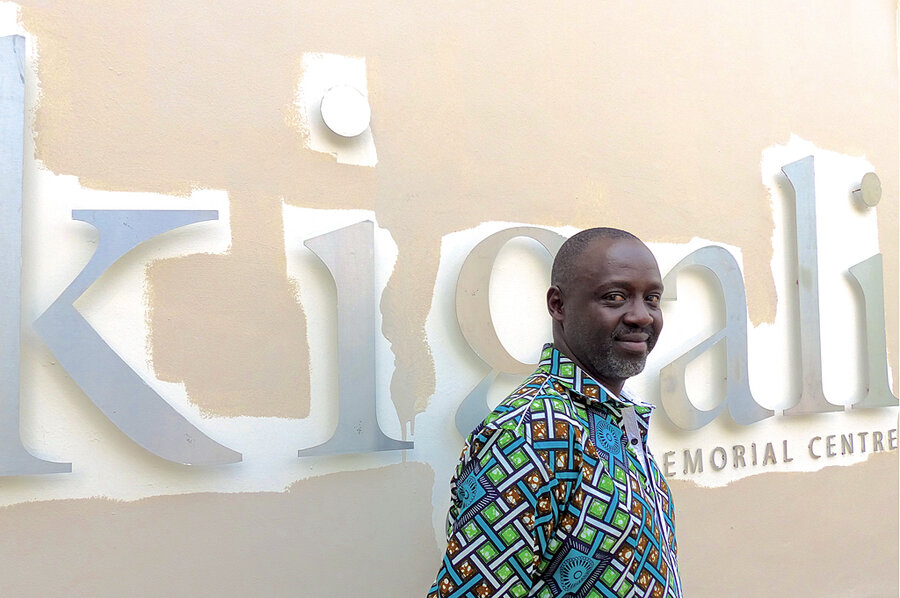

Jean Paul Samputu practices forgiveness – even for his father's killer

Loading...

| Kigali, Rwanda

Forgive your father's murderer? Unlikely, right? Probably impossible? Unless, like Rwandan peace activist and renowned musician Jean Paul Samputu, you want to save your own life from self-destruction, misery, and pain.

A quick historical review: 19 years ago, over a 100-day period, nearly 1 million Rwandan Tutsis lost their lives at the hands of their fellow Rwandans, the Hutus.

Prior to the outbreak of the genocide on April 6, 1994, Mr. Samputu, a Tutsi and at the time a rising star on the East African music scene, spent six months in jail, along with thousands of other Tutsis who had been arrested at their homes.

The jails were packed, and the United Nations and international community demanded that the government release the prisoners. The Tutsis were released, but a plan was hatched to eliminate them. Portrayed in the award-winning film "Hotel Rwanda," this swift and brutal genocide eventually stirred the conscience of the world. But at the time, no foreign government intervened to prevent the Hutus from carrying out the slaughter of their own Tutsi friends and neighbors.

After Samputu was released from jail, his father urged him to flee the country.

Refusing to leave himself, the elder Samputu stayed behind in his village, while Jean Paul escaped to neighboring Burundi and Uganda. In the nightmare of genocidal rage that followed in Rwanda, Samputu lost his father, mother, three brothers, and a sister.

He never found out how his family died, other than his father. When Samputu returned to his village, he discovered that his father had been murdered by a neighbor, Vincent, who since childhood had been the family's good friend.

Struggling with grief, anger, and desperation, Samputu left his village and went to Kigali, the Rwandan capital, to continue performing. His private demons, however, overwhelmed any joy or success he had previously experienced. His increasingly public slide into drinking and drugs caused him to lose respect in the Rwandan music world.

In 2002, he returned to Uganda, where his rage and resentment boiled over, causing his career, his health, and his private life to spiral downward. Friends sought to help him, even bringing in witch doctors.

"But I was just waiting to die," Samputu says. Someone finally brought a Christian pastor, who prayed for him. He says that "a power I cannot describe" completely filled him up and gave him peace for the first time since the genocide. He became a Christian.

But he knew that something remained: unforgivingness, anger, bitterness, he says.

In 2003, Samputu found himself on Prayer Mountain, a real place in Uganda. There, he says, God showed him that he needed to forgive. "That's when I said yes to God – I can forgive."

That day, Samputu says, he was finally free: "I got a great peace in my heart." He also felt that he would win the Kora (the African Grammy) and that he would take his message of forgiveness all over the world.

He returned to Rwanda. The government had embarked on a campaign of reconciliation between Hutus and Tutsis. But in Samputu's village and in villages throughout Rwanda traditional gacaca meetings were also taking place.

Practiced throughout Africa, this process brings victims and perpetrators together in a public assembly. These confrontations allow for immediate, personal, and honest dialogue in the public square – without the need for formal councils and commissions. In Rwanda, those imprisoned for their crimes had to attend the gacaca meetings once a week to be accused. The convicts then returned to prison.

First, Samputu visited a jail and discovered that Vincent had been incarcerated for his crimes. Then Samputu visited Vincent's wife to tell her that he had forgiven her husband. Astonished, she said that she, herself, had not forgiven her husband, so how could Samputu?

Later, when Samputu went to participate in the gacaca, he announced that he had forgiven Vincent (although he didn't know that Vincent was there).

His former friend stepped forward, stunned, asking, "Am I dreaming?" Vincent could not understand how Samputu could forgive him, because he couldn't forgive himself. Samputu says that in time, however, "through God," Vincent did learn to forgive himself.

But Samputu wanted to know, why did Vincent murder Samputu's father? How could Vincent murder a neighbor, the father of his childhood friend?

Vincent said that the "law of the genocide" dictated that the one closest to the victim had to do the killing. Despite the irrationality of this explanation, the two men worked together over the next few years to bring their message of forgiveness to all of Rwanda.

That same year, Samputu's career did take off. He won the Kora Award for Most Promising African Male Artist. Three years later, in 2006, he won First Place for World Music in the International Songwriting Competition with "Psalm 150." And in 2007, he was recognized as an "ambassador of peace" by the Interreligious and International Federation for World Peace.

Samputu also formed a music and dance group in 2007 called Mizero Children of Rwanda (mizero means "hope" in the Kinyarwanda dialect). These 15 children, orphaned by the genocide, traveled with him throughout Africa, Canada, and the United States, singing, dancing, and delivering a message of forgiveness.

In 2009, Samputu and others organized a Conference on Reconciliation in Rwanda, which provided the first public event where Samputu and Vincent told their story.

Today, Samputu is an international ambassador for peace, speaking at the UN and at universities throughout Japan, Canada, the US, and Germany. His nonprofit group, The Mizero Foundation, focuses on teaching gender equality and the empowerment of women.

American ethnomusicologist Brent Swanson, who teaches at the Frost School of Music at the University of Miami and the School of Music at Florida International University, met Samputu in Rwanda in 2009.

Samputu makes a huge impression on audiences at concerts, Mr. Swanson says. After hearing Samputu's story, people are willing to forgive, to "hand themselves over to whatever consequences might follow," he says.

Since the genocide, Rwanda has made enormous progress. After forming a "government of unity and reconciliation," the country's official policy today is one of restoration and forgiveness. Identity cards no longer show a tribal designation, a practice that had played a pivotal part in separating Hutus and Tutsis since the days when Belgian colonizers ruled Rwanda.

Another American, Bruce Cripe, who spent 30 years at the charity World Vision and is now chairman of Global Assistance Group Inc., a foundation that garners funding for developing countries, calls Samputu a "brother – a man with a huge heart." They have traveled Africa together, and on behalf of World Vision, Mr. Cripe commissioned Samputu to work in villages to help heal the scars left by the genocide.

The work Samputu undertook was often at his own peril because people didn't think they wanted forgiveness, Cripe says. "At that time, the government [was] interested in reconciliation, but not forgiveness. Jean Paul even had death threats against him," he says.

Initially, Samputu lost friends. Even his relatives opposed his work on forgiveness, he says. But he feels that attitude is changing.

"Forgiveness is for you, not the offender. Forgiveness is the only thing that can stop the cycle of violence, the culture of revenge," Samputu says. "If we don't want another genocide, our children must learn this message."

Cripe has witnessed firsthand Samputu's influence, both on the Mizero Children of Rwanda and children on the streets. Through his music and his foundation, Samputu is redirecting their way of thinking away from revenge and hatred, Cripe says. "He's so warm and charismatic. People love him. But more importantly, they listen to him. They know he speaks the truth."

• To learn more about Samputu's work visit http://mizerofoundation.org.

Help war-torn countries

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations worldwide. Projects are vetted by Universal Giving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

Below are three groups selected by UniversalGiving that support rebuilding in Rwanda and other war-torn communities:

• The GVN Foundation supports the charitable and educational work of local community organizations. Project: Volunteer with children and communities in Rwanda.

• Aid and Care Inc. works to help vulnerable people and war-affected communities in Africa. Project: Support the education of girls and orphans in Rwanda.

• Asia America Initiative promotes social justice and economic development in impoverished, war-torn communities. Project: Support music programs in schools that build peace.