John Hope Bryant wants African-American students to be smart about money

Loading...

| Baltimore

In a Baltimore classroom, Dionne Waldron is engaging a class of sixth-graders in an unusual topic: money.

And it’s really about more than that. As Ms. Waldron coaches them on subjects such as bank accounts, credit, and interest payments, she also weaves in phrases such as “smart decisions,” “dignity,” and “living up to your potential.”

She’s not only teaching financial literacy – but also why it matters.

Armed with enthusiasm and a joyful smile, she encourages students to remember three big ideas using gestures: a hand over their heart for self-respect, a hand held out for respecting others, and a hand held high for reaching one’s potential.

The group behind this instruction is called Operation HOPE, and it is helping to fill a yawning gap that many finance experts see between what Americans know about money and what they need to know. The group’s motivating force, however, is really about instilling those deeper values that Waldron is nurturing.

The goal is to help people lead successful lives – especially people who come from lower-income backgrounds, as many of Waldron’s students on this day do.

“There’s a difference between being broke and being poor,” says John Hope Bryant, Operation HOPE’s founder. “Being poor is a disabling frame of mind.”

He urges people to vow never to be poor – and Operation HOPE is trying to help as many people as possible achieve that goal. Working from its base in Los Angeles, the group has a national and even global reach. Its activities range from classroom lessons to coaching sessions for adults who want to take out bank loans or learn how to be entrepreneurs.

Mr. Bryant has seen both financial adversity and success. As a young African-American in Los Angeles in 1992, with his own finance business chugging along nicely, he saw riots break out after the acquittal of police officers who had beaten black taxi driver Rodney King.

The frustration and destruction in his community spurred Bryant to coordinate local bankers in a financial relief effort – and ultimately moved him to launch Operation HOPE.

“I want to teach you how to fish – and get you out on the lake,” he says in a phone interview from his home in Atlanta, referring to the idea of empowering people with knowledge so they can help themselves – instead of addressing poverty only through temporary assistance.

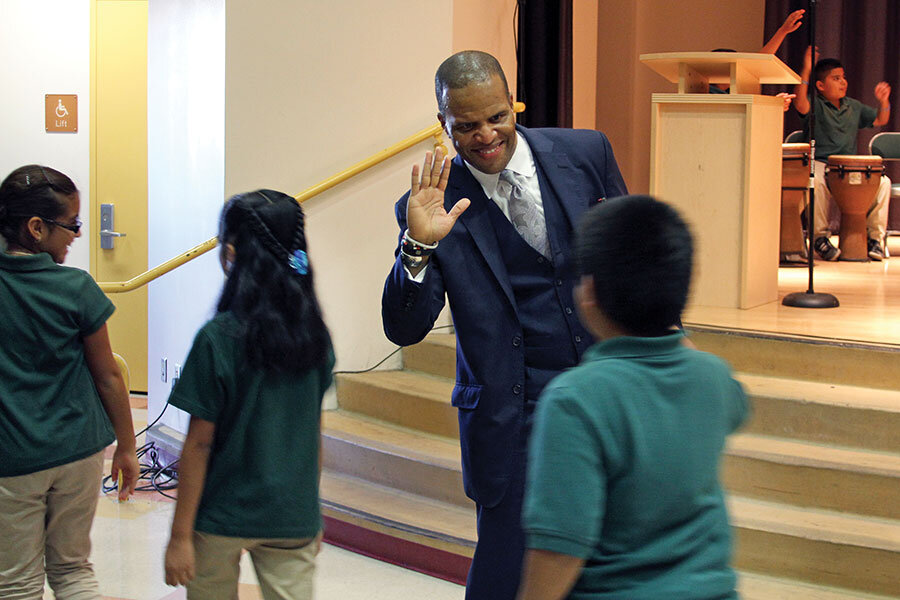

African-Americans, such as those here at Holy Angels Catholic School in Baltimore, especially need this support, Bryant says. He draws inspiration from the way Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Lincoln looked at the idea of empowering African-Americans through economic freedom. (His home church in Atlanta, Ebenezer Baptist Church, is where Martin Luther King Sr. and Jr. were pastors.)

“Can you imagine if Lincoln had survived” instead of being assassinated in 1865, Bryant says, noting Lincoln’s plans to grant farmland to freed slaves and to found a bank for them.

In Bryant’s view, much of the unrest in the world has roots in poverty, when that’s understood as a shortage of hope, love, opportunity, and self-esteem.

Not everyone may view poverty through the same lens as Bryant, but economists who study the issue widely agree on the need for better financial literacy in American society – everything from how to budget and borrow to how to save for retirement. Annamaria Lusardi, an expert in the field, has written that financial education should start at a young age and that it “can be of substantial help to the least financially literate.”

Operation HOPE is not the only nonprofit aiming to meet these needs.

“People really need life skills,” says Ted Beck, president of the National Endowment for Financial Education, a large nonprofit that spreads financial concepts in schools and workplaces. The consequences of not learning them, he says, can be missteps at key points, such as when buying a home or starting a retirement account.

“People get painted into financial corners, and it ends up having a big impact on their lives,” Mr. Beck says.

By contrast, one study in January by academic and Federal Reserve experts found “notable improvement” in measurements such as credit scores in states that required personal-finance instruction as part of high school curricula.

Beck says he hasn’t evaluated Operation HOPE’s programs, but he knows Bryant from having served alongside him on presidential commissions on financial literacy.

“John has done a very good job of reaching out to communities ... and getting people very excited about it,” he says.

Now Bryant and his team at Operation HOPE have hit on a new strategy to reach adults who need help with banking, borrowing, and starting businesses.

Just as Operation HOPE partners with schools (public and private) to reach students, it has begun partnering with banks around the country. Banks such as SunTrust let Operation HOPE use some of their space for a “HOPE Inside” program, and in return they often get new customers. Meanwhile, the HOPE Inside program helps people improve their credit scores, open bank accounts, obtain loans, and launch businesses.

Sitting in office space donated by SunTrust, Cynthia Harrison is the human face of HOPE Inside in downtown Washington. The group’s mission in banks like this one is not just to assist low-income people who are “unbanked,” she says, but also middle-income people who can use help on such things as improving credit scores.

People also come to HOPE Inside to learn how to start their own businesses, so they are not dependent on an employer for security or opportunity. Bryant says that stepping up formation of new businesses is part of “how the poor can save capitalism,” to quote the title of his most recent book.

Giovanni Wade is one of the people who’s been through a 12-week Operation HOPE entrepreneurship class with Ms. Harrison. Drawing on the skills he’s learned, he left a program-analyst job with the federal government to pursue his goal of self-employment as a budget consultant for private-sector clients.

“You kind of encourage one another,” Mr. Wade says of the others with whom he studied. Harrison prodded them forward, helping them hone everything from their feasibility research to their “elevator pitch” to their list of potential lenders or investors, he says.

The program, which covers material similar to what is taught in college classes in business, is free. But participants have to be ready for Harrison’s brand of tough love.

“You have to knock the door down, or walk around it,” she says of the obstacles her students must be prepared to meet.

When Gwynette Hortman-Morris arrived at the HOPE Inside office, she had an idea for a service she wanted to provide – a home for young people who are transitioning out of foster care but aren’t yet ready to live on their own.

“It was something the Lord put in me,” she says, but she had “no idea how to do it.” Harrison helped her figure out a business plan, complete with a compelling PowerPoint presentation.

Even getting her master’s degree in theology “was not as hard as this course,” Ms. Hortman-Morris says.

Operation HOPE is now active in a number of big US cities from Philadelphia to Los Angeles. It has reached some 830,000 schoolchildren and is trying to rapidly expand the number of HOPE Inside centers at banks around the country.

Behind it all is the vision of Bryant and his colleagues that this effort can have a transformative effect. He calls it a “radical movement of common sense that I think will change America and may change parts of our world in our lifetime.”

Back in the Baltimore classroom, when Waldron asks what a credit score is, one young boy comes up with an answer.

“It’s when the bank has a good record of you,” he says.

That’s the kind of understanding Operation HOPE wants more Americans, young and old, to have.

“Why set goals?” Waldron asks the boys and girls. “Because if you’re aiming for nowhere, that’s just where you’ll go.”

• Learn more at www.operationhope.org.

How to take action

Universal Giving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by Universal Giving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are three groups that help move families out of poverty:

• Supporting Kids in Peru helps children in El Porvenir, Peru, receive an education through programs focusing on the economic, emotional, and social development of each child and parent. Take action: Volunteer as an economic development project officer.

• Develop Africa establishes meaningful and sustainable development in Africa through capacity building and education. Take action: Help expand a small business.

• KickStart International Inc. creates opportunities for poor, rural farmers in sub-Saharan Africa to make money and offers a solution to the deepest root of poverty: lack of income. Take action: Help lift a family out of poverty.