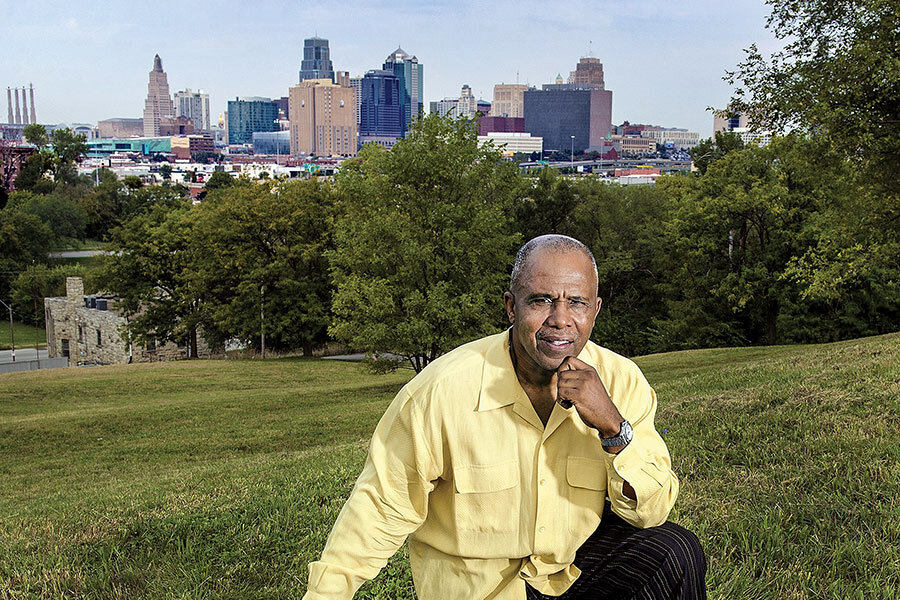

Vewiser Dixon's ambitious vision: make inner-city Kansas City a 'black Silicon Valley'

Loading...

| Kansas City, Mo.

For Vewiser Dixon, a successful career in business has always been as much about helping others as about making money.

In addition to pursuing his own business ventures, Mr. Dixon has spent his time, energy, and money over many years nurturing minority start-up businesses as well as mentoring young entrepreneurs.

Today, as both a businessman and ordained minister, Dixon is engaged in his most ambitious project yet – turning a decaying neighborhood on the east side of Kansas City, Mo., into a thriving, technology-oriented community.

“I want to create a black Silicon Valley,” Dixon says. “Everything we do today is driven by technology. But African-Americans and other minorities are usually the last ones to enter those kinds of fields. High-tech jobs are the new promised land for minorities.”

Vewiser (“VEE-wiser” or “V,” as he is known to friends) Dixon was born and raised in the famed 18th & Vine jazz district of Kansas City. After earning a college degree in mechanical engineering, he moved to Detroit where he worked for 10 years in the automobile industry. By the 1980s, his old neighborhood, where Kansas City jazz was born, was long past its prime and, like inner-city areas across the country, suffering economically.

Dixon left his corporate job in Detroit, moved back to town, and opened a restaurant in his old neighborhood, which is still in operation today. He also bought and renovated a building in the area, then used $100,000 of his own money to start the Kansas City Business Center for Entrepreneurial Development, the city’s first minority business incubator. Funded by profits from the restaurant, and without using any government money, the incubator has helped launch scores of minority-owned businesses.

Dixon has also informally mentored many young people, predominantly African-Americans. One of those is Lucy McFadden. After graduating from cosmetology school in the early 1980s, and with little business knowledge or experience, she rented a station in a beauty salon Dixon owned.

After the leaseholder moved away, Dixon let Ms. McFadden take over the entire salon on a pay-what-you-can basis. The boost Dixon gave McFadden early in her career allowed her to develop as a hairstylist and as a businesswoman. Today she owns four businesses in Kansas City – two beauty salons and two barbershops.

“It was because of V that I learned about business,” McFadden says. “Any question I ever had, he would sit down for hours and talk with me. It was never, ever about money with him. If he was just into making money, he could be very wealthy. He just enjoys helping people and giving back.”

Despite his success, Dixon was not satisfied. “I was doing all these things in business, but it really wasn’t fulfilling me,” he says. “I always had a heart for community, but I also had a higher calling.”

In the 1990s Dixon yielded to that calling. After divesting himself of his business interests, he attended divinity school in Denver, then moved to St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands to help a dying friend put his business affairs in order. He stayed on in St. Croix for 10 years doing missionary work.

When he returned to Kansas City in 2003, he found it difficult to reconcile his business acumen with his spiritual calling.

“At the time there was really no model for me to emulate,” he says. “That’s what I struggled with. Then I realized I was already doing the work of the ministry in the workplace, even before I answered the call. My ministry has always been helping people achieve self-sufficiency and economic independence. I preach that in the marketplace, not in church.”

Today, Dixon is applying his particular brand of “marketplace ministry” to a project that is both highly ambitious and considerably different from his previous endeavors.

Over the past several years, he has quietly acquired 144 parcels in the South Vine Corridor, the largely abandoned neighborhood immediately south of the historical jazz district. He hopes to develop this into a self-contained community with residential, retail, and professional space. He also plans to bring in an early childhood center and a university to complement the nearby elementary, middle, and high schools.

When completed, his proposed Enterprise Village Ecosystem (EVE) will focus on high-tech education that, combined with business support, he hopes will create the fertile ground needed to launch minority-owned technology start-up companies.

“I want to create a start-up village with everything people need to live, work, and play here,” he says.

It’s a lofty goal, but Dixon has made significant headway. In addition to the thorny task of securing the 17.5 acres of contiguous lots, he has lined up a grocery store to go with the 100 apartments that will be built during the first phase of the project, which he hopes to start this year.

He is also in preliminary discussions with the Missouri University of Science and Technology in Rolla (his alma mater) about establishing a satellite campus in the South Vine Corridor.

Part of Dixon’s strategy is to court large, national technology companies, many of which are failing to meet their diversity goals and generating bad publicity for themselves as a result.

He hopes that having an educated workforce living and working in the area will encourage some of these companies to open businesses and franchises in his enterprise village.

Dixon is also in preliminary discussions with former basketball star Magic Johnson. The connection was made through Dixon’s longtime friend former National Basketball Association player Clay Johnson (no relation), who played with Magic Johnson on the world champion 1982 Los Angeles Lakers team. Since his retirement from the game, Magic Johnson has invested time and money in similar technology and community development projects, primarily in Detroit.

Clay Johnson says he is hounded constantly with business opportunities people would like him to present to Magic Johnson, but he says Dixon’s is different.

“I think EVE is a great idea,” he says. “V is always thinking about how he can [improve] somebody else’s life. EVE is going to have a big impact on a lot of lives in this community.”

The South Vine Corridor is sorely in need of redevelopment, having suffered decades of residents moving away. If anyone can pull off a project as ambitious as EVE, it may be Dixon, who inspires confidence among many local leaders.

“I think the key word is relationships,” says Chester Thompson, president of the Black Economic Union of Greater Kansas City, a nonprofit group that is redeveloping Kansas City’s urban core and is partnering with Dixon on EVE.

“V is very well connected nationally and internationally,” Mr. Thompson says. “EVE has gotten tremendous interest from a lot of different people who can see the value of it.... I think V is just who we need to make this come alive.”

Dixon has also earned the respect and support of Democratic Rep. Emanuel Cleaver II, who has represented Missouri’s Fifth District, which includes Kansas City, in Congress since 2005.

Like Dixon, Mr. Cleaver is an ordained minister. He was active for 20 years in local politics, serving for 12 years on the city council and for eight years as mayor of Kansas City. During that time, Cleaver worked hard to redevelop the jazz district.

“I’m excited about it,” Cleaver says of EVE. “For a variety of socioeconomic reasons it’s always difficult to attract private development investment to the urban core. I had a lot invested in 18th & Vine, so when someone like Vewiser comes along with an exciting plan, he’s going to get my support, particularly if it is somebody who is as energized as Vewiser.

“He is fired up about this and tends to fire up everybody who’s around him and will listen.”

Dixon hopes to break ground on the first phase of EVE this spring. Until then, he plans to respond to the many inquiries he has received from developers interested in being part of the project.

“This was a busy, thriving area when I was growing up,” Dixon says of the South Vine Corridor. “I want to see that again.”

How to take action

Universal Giving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects are vetted by Universal Giving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause. Below are links to three organizations that help increase business and economic opportunities in communities worldwide:

• KickStart International Inc. creates income-generating opportunities for poor, rural, entrepreneurial farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Take action: Empower a couple to emerge from poverty.

• Develop Africa changes lives by sending children’s books to schools and building libraries. Take action: Help expand a small business.

• Global Citizens Network provides immersion experiences for volunteers. Take action: Revitalize community projects for Tibetan refugees.