How the Founding Fathers grappled with hostage ransom demands

Loading...

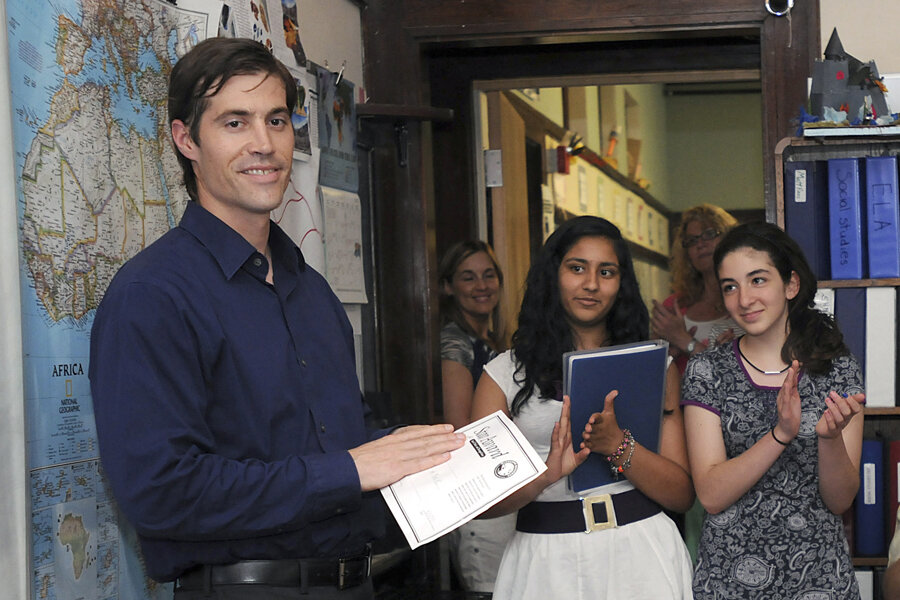

The US debate over paying ransoms to kidnappers – revived by the murder of freelance journalist James Foley – isn't a new one. America's Founding Fathers were also preoccupied by the issue while confronting "unconventional foes" on the high seas.

In the late 1700s, Barbary pirates in northern Africa were regularly capturing foreign ships and holding crews for ransom. In 1795, the US paid almost $1 million, a frigate, and related materials in return for the release of 115 American sailors who were being held by the ruler of Algiers, according to the Library of Congress. The US government also paid regular tributes so that its ships could enjoy safe passage.

Thomas Jefferson strongly opposed paying tributes. After hearing of the seizure of an American ship in 1784, he said, “Our trade to Portugal, Spain, and the Mediterranean is annihilated unless we do something decisive. Tribute or war is the usual alternative of these pirates.”

A decade later, Congress agreed to fund the construction of a blue-water navy, starting with six frigates. This was the stirrings of US naval power projected internationally.

When Mr. Jefferson became president in 1801 he refused to continue paying tributes, leading to the First Barbary War. In 1803, the US frigate Philadelphia was captured in Tripoli and its crew taken hostage. Jefferson, despite his opposition, authorized a ransom payment of $60,000. It wasn’t until the Second Barbary War in 1815 that the US stopped paying all tributes.

In recent decades, the US has continued to deal with kidnappings and large-scale hostage situations with varying degrees of success. Presidents have often attempted to rescue Americans held overseas, rather than cede to captors' demands. In the case of Mr. Foley, US troops staged an unsuccessful raid in Syria earlier this summer.

The 444-day Iran hostage crisis in 1979, which involved 52 American diplomats and citizens, drew fierce debate. President Jimmy Carter restated American policy in his 1980 State of the Union address, “Our position is clear. The United States will not yield to blackmail.” After a failed American rescue operation, negotiations finally led to the hostages' release under President Reagan in January 1981.

Ransoms and rebels

In contrast to the US policy, many European countries have paid large sums in recent years to free their citizens. The self-proclaimed militant group the Islamic State (IS) had demanded a ransom of 100 million euros ($132 million) for Mr. Foley.

As the Monitor reported, US policy follows a much stricter line than Europe. “[T]he US will actually prosecute a private company or organization that pays a ransom for an employee on a charge of funding terrorism.”

When it comes to the kidnapping of private citizens, such as journalists, outcomes have varied dramatically. Some journalists, like David Rohde have managed to escape from captivity. Mr. Rohde was held for seven months after being kidnapped by the Taliban in Afghanistan in 2008. In the 1990s, he was also captured and held in Bosnia.

Rohde wrote an opinion column for Reuters asking, “Did America’s policy on ransom contribute to James Foley’s killing?” He wrote, “It [Foley’s murder] is the clearest evidence yet of how vastly different responses to kidnappings by U.S. and European governments save European hostages but can doom the Americans.”

As The New York Times reported, Foley’s execution-style murder is the second of a Western journalist at the hands of Islamic extremists since the 2002 killing of Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl in Pakistan.

While the US refuses to pay ransoms, it has, however, traded prisoners of war; in June, Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl was released in exchange for five Taliban prisoners. This has raised further questions about when and how it is appropriate to engage in such exchanges. The Government Accountability Office said Thursday that the administration had broken the law by releasing the Taliban prisoners without notifying Congress 30 days in advance.

Several other Americans are still being held by IS, including Steven Sotloff. The Times says at least three are in IS custody. So President Obama is again faced with a difficult choice, just as the Founding Fathers did over two centuries ago.