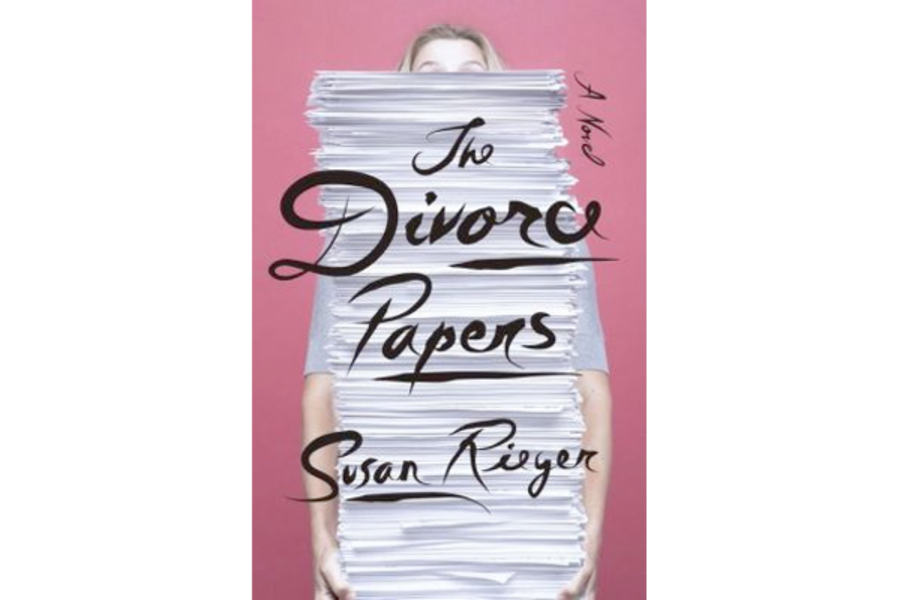

The Divorce Papers

Loading...

The case file of a bitter divorce doesn’t sound like the most obvious choice for those looking for a witty, charming read.

But Susan Rieger’s new novel The Divorce Papers has more snap and freshness than a just-picked stalk of celery.

In her debut novel, Rieger gooses the epistolary form by adding emails, interoffice memos, letters (some hand-written), medical reports, and court documents in the tale of a young criminal lawyer who gets handed her first divorce case. Rieger doesn’t give herself any literary loopholes. There is no narrative text or explanatory dialogue: The case file is the entire novel.

It’s an ambitious undertaking, but Rieger, who has taught law and Columbia and Yale Universities, pulls it off with aplomb.

(The novel-in-letters appears to be making a small comeback this spring among debut novelists. Aaron Their’s “The Ghost Apple” lampoons corporate venality and ivory tower mores, using emails, recruiting pamphlets, blog entries, diaries, minutes from faculty meetings and newspaper clippings to document the way that Tripoli College, most famous for its all-you-can-eat pudding bar, turns to corporate sponsorship to survive the loss of roughly half its endowment during the financial downturn.)

In “The Divorce Papers,” Sophie Diehl, Esq., was perfectly happy representing criminals and “meth heads” at Traynor, Hand, Wyzanski. She gets roped into representing Mia Durkheim, the daughter of a Very Important Client, after Mia’s oncologist husband serves Mia divorce papers in her favorite restaurant. Then things get really ugly.

“Divorcing couples harbor murderous thoughts; they just have better impulse control than your regular clients,” a senior partner at her firm tells Sophie, saying that she might enjoy the change.

Sophie, however, is quite certain that she is completely ill-equipped to take on the case, which involves a fair amount of money, inherited property, infidelity, and, oh yes, one brokenhearted little girl. Defending criminals is far less messy, she thinks.

“I like that most of my clients are in jail. They can’t get to me; I can only get to them,” she writes back to the partner. “I don’t like divorcing parents. I had my very own set, both of whom behaved very, very badly in ways that would make your hair stand on end.”

Nonetheless, she is a very junior lawyer and Mia’s dad is a very, very important client. As the case of Durkheim v. Durkheim unfolds, readers get to know Sophie, an engagingly offbeat heroine who harbors certain insecurities about her brilliant French mother, as well as Mia and Daniel, their daughter, and Mia’s Brahmin father.

With her wealthy, patrician roots, Mia is a touch brittle to carry a novel. (“I find my divorce mentally stimulating – when it’s not emotionally shattering,” she tells Sophie at one point.) Fortunately, Sophie is there to step in with all the gameness of a heroine from a screwball comedy.

“The Divorce Papers” is built around an undeniably clever conceit. But it’s the humor and charm with which Rieger have imbued her novel that make her debut such a memorable read.

Yvonne Zipp is the Monitor fiction critic.