It is one of the most heartbreaking set-ups: A loved one is killing themselves with an addiction, and all you can do is watch.

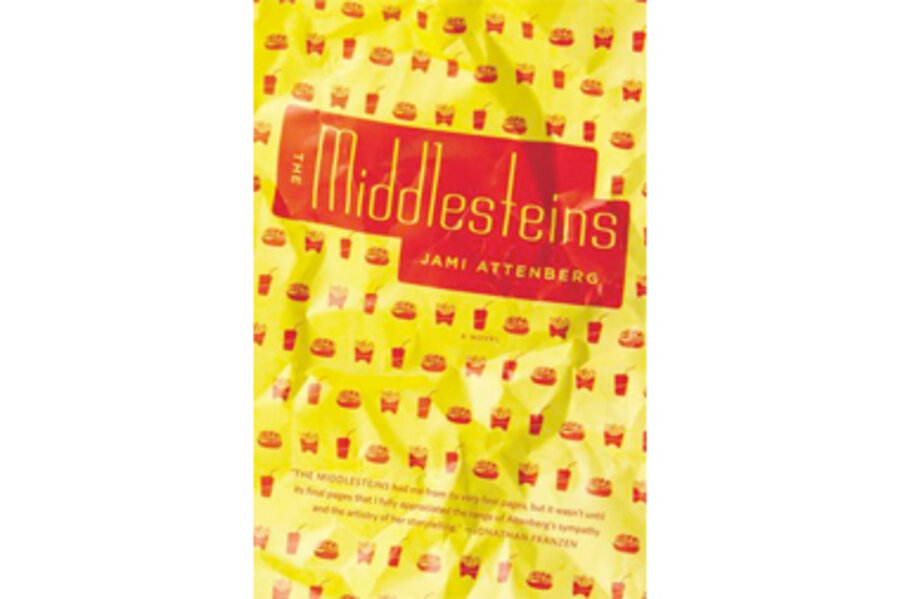

“How did she get to this point? And more important, what are we going to do about it?” a character asks in Jami Attenberg's funny, compassionate tragicomedy, The Middlesteins.

In an increasingly common development, her protagonist isn't on alcohol or drugs. Edie Middlestein is eating herself to death.

The lawyer and mom of two adult children is over 300 pounds, diabetic, and, her doctor warns, has only months to live if she doesn't stop.

“Rachelle's mother-in-law was not well. Rachelle wouldn't have described her as sickly, though, because there was nothing frail about her. Edie was six feet tall, and shaped like a massive egg under a rotating array of silky, shimmering housedresses that seemed to make her glow.”

Edie's husband, Richard, has just left her, saying he just can't watch what she's doing to herself another day, leaving her wary daughter, Robin, her gentle son, Benny, and his perfectionist wife, Rachelle, to try to help Edie.

They are not, as it happens, ideally suited for the job: Rachelle follows Edie from fast-food joint to fast-food joint, appalled, and starves Benny and their kids with raw vegetables and brown rice in an effort to make sure Edie's illness isn't passed on to the next generation. Robin, a history teacher who runs five miles a day, drinks too much and pushes people away, and Benny, who takes pride in being a number-cruncher, smokes a joint nightly and pretends that all is well.

Richard, meanwhile tries to date divorcées and widows in their 40s and can't understand why his children are so furious with him at abandoning their gravely ill mother.

“Therapy was for people who had an interest in communication. This was not the Middlestein family, at least not anymore,” Benny thinks.

Each Middlestein gets weighed on the scales as Attenberg looks back at Edie's life, with each chapter marked by pounds, starting when she was 5 and already weighed 62 pounds. "How could she not feed her?" her mom thinks, handing over food to soothe the child's hurts.

As a precocious teen, who would graduate from high school and college early, Edie “ate on behalf of Golda, recovering from cancer. She ate in tribute to Israel. She ate because she loved to eat. She knew she loved to eat, that her heart and soul felt full when she felt full.”

Attenberg seems most in tune with Robin, but “The Middlesteins” overall is notable for the nimble way it combines humor and pathos. Attenberg can be wry and sharply funny, but there's a tenderness in her portrayal of her outsized main character and her family.

At one point, Benny sits up in the kitchen so Edie doesn't succumb to the siren call of potato chips and onion dip the night before a surgery. (She has to have an empty stomach, or she could die. In her heart-breaking calculus, Edie figures that onion dip really almost qualifies as a liquid.)

“He respected his mother, because she had raised him with love, because she was a smart woman, even though she was also so incredibly stupid. Also, he respected humanity in general. He respected a person's right to weakness. For all these reasons, he never told anyone he stayed up late waiting for his mother, not even his wife. What happened in that kitchen was between Benny and Edie. With grace, he offered his love and protection, and she accepted it, tepidly, warily. It did not bring them closer together, but it did not tear them apart.”

"The Middlesteins" offers a similar generosity toward weakness while clearly delineating its cost.