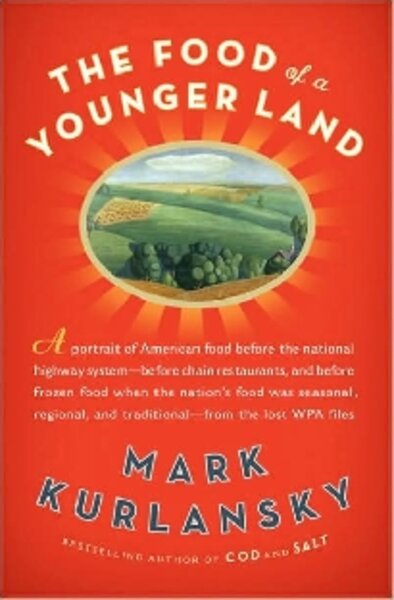

The Food of a Younger Land

Loading...

Food was local, seasonal, and produced on a small scale. Social life revolved around harvests, public suppers, and feasts. And thousands of unemployed writers were given jobs chronicling, among other things, the way the country ate. Sound like heaven? Actually, this was the United States three generations ago.

The Food of a Younger Land, the latest book edited by Mark Kurlansky, is a collection of food writing that traipses in and out of kitchens, church suppers, and lumber camps to paint a portrait of American food culture in the 1930s and early ’40s, before it was forever changed by the advent of national highways, fast food, and industrial agriculture.

The book collects writing produced by the Federal Writers Project (FWP), a Works Projects Administration program that employed nearly 7,000 writers at its peak. Though most of its writers were novices, luminaries such as Saul Bellow, Eudora Welty, Richard Wright, Studs Terkel, and Zora Neale Hurston are among its alumni. FWP writers collected oral histories and wrote ethnographies and guidebooks.

In the late 1930s, the FWP turned its attention to food, beginning a book that was to be called “America Eats.” Food writing at that time was largely confined to recipe books and women’s magazines that “followed the belief that women were not interested in politics and social problems,” Kurlansky writes. In contrast, this book was to approach food seriously and divide its attention evenly between the food itself and the customs and culture that surrounded it.

But World War II changed all that. “America Eats” was abruptly abandoned after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the unedited manuscripts were sent to the Library of Congress. A few years ago, Kurlansky stumbled upon the boxes in the course of research for another book, and gleaned “The Food of a Younger Land.”

A highlight is Mari Tomasi’s essay, “Italian Feed in Vermont.” The city of Barre was a granite center and drew droves of skilled carvers from northern Italy. But the trade was a dangerous one and made widows of many young wives. To support their children, some of these women opened their home kitchens, cooking “Italian feeds” for truck drivers, bureaucrats, and other professionals.

Tomasi describes the scene in Maria Stefani’s dining room after the appetizers and pasta course: “The food looks good; it tastes better. Geniality expands. Stomachs gorge in leisurely contentment. Belts loosen. Maria’s daughter, in horror, lest glutted appetites fail to appreciate the joys yet to come, hints subtly to novices, ‘Will you have salad with your meat? And will you have fried chicken or chicken alla cacciatore?’”

Another gem is William Lindsay White writing on barbecue, Kansas-style, which means cooking a steer underground for 30 hours. The meat must be eaten within an hour of being carved, he warns, for “if the sun ever rises on Barbecue its flavor vanishes like Cinderella’s silks and it becomes cold baked beef – staler in the chill dawn than illicit love.”

Forget about finding barbecue at a roadside joint; the best is found at celebrations. White writes, “True barbecue, like true love, cannot be bought but must always be given, and so is found only as a part of lavish hospitality in the cow country.”

And then there’s Claire Warner Churchill’s venomous denouncement of the mashed potatoes served in restaurants: “No, I am not to be fooled by your whipped potatoes, your fluffed potatoes, your watered pastes that pass in many restaurants for honest to God mashed potatoes. I know them for what they are: horrible travesties upon a self-respecting dish of mashed, and I mean mashed, not macerated potatoes.”

Though many of the essays concern rural delicacies such as beaver tail, chitterlings, and maple sugar, city life is represented, too. There’s a snappy paean to a mechanical lunchroom called the Automat; an account of the famous Los Angeles chili and burger stand, Ptomaine Tommy’s; and a long list of soda fountain slang: “Nervous Pudding” is a gelatin dessert. A “pot walloper” is a cook. And “Yesterday, today, and forever” is hash.

The book’s biggest weakness is its unevenness – which is not too surprising, given that manuscripts were lost and many FWP writers were inexperienced. And though it does represent much diversity, Jewish and Asian food are missing.

Racism is also evident throughout. In many places, rural blacks are quoted in dialect, while their white counterparts, who surely also spoke a distinctive English, were not.

But overall, “The Food of a Younger Land” succeeds at giving a snapshot of the US’s food system just before it was radically altered by changes in infrastructure, culture, economy, and – sadly – the deterioration of the environment.

Kurlansky writes: “But the most striking difference of all was that in 1940 America had rivers on both coasts teeming with salmon, abalone steak was a basic dish in San Francisco, the New England fisheries were still booming with cod and halibut, maple trees covered the Northeast and syruping time was as certain as a calendar, and flying squirrels still leapt from conifer to hardwood in the uncut forests of Appalachia.”

Though the essays in this book were written some 70 years ago, the food system they depict is remarkably like the one the Michael Pollans and Alice Waters of the world today argue for so passionately – one that narrows the gap between consumer and producer, is sustainable, and resituates breaking bread together to the center of our culture.

Bridget Huber is a Monitor intern.