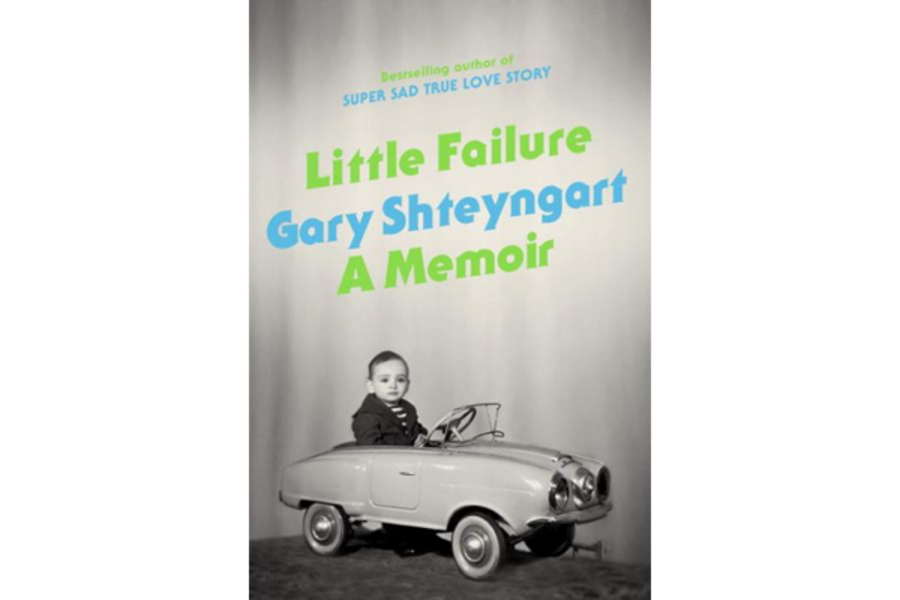

Little Failure

Loading...

Little Failure, Gary Shteyngart’s alternately hilarious and surprisingly sincere memoir, is written very much from the vantage point of success. Shteyngart has already published three highly acclaimed, scathingly funny satirical novels – “The Russian Debutante’s Handbook,” “Absurdistan,” and “Super Sad True Love Story” – and has been hailed as a successor to no less than Saul Bellow and Philip Roth.

“Failurchka” – “Little Failure” – is a hybrid English-Russian “endearment” Shteyngart’s tough-love Soviet-born parents coined for their asthmatic, anxious only child after they emigrated from Leningrad to the United States in 1979, when he was 7. Another moniker was “Soplyak,” which translates as “Snotty” – hardly catchy-title material.

Shteyngart’s self-deprecating memoir takes apart and reassembles what he calls the “nesting doll of memory” to chronicle his path from a sickly “Marcel Proust-looking boy” obsessed with cosmonauts and Lenin to an aspiring Republican and awkward misfit at a conservative Hebrew day school in Queens, N.Y., where he learned to wield humor and storytelling to gain acceptance.

Although he managed to shed his Russian accent, his loneliness and sense of alienation clung to him through his years at Manhattan’s prestigious Stuyvesant High School, flannel-clad Oberlin College, and early jobs writing for nonprofits in New York City. He is unsparing in his description of the steady infusion of alcohol and marijuana with which he anesthetized himself. His extended, inebriated blue period is not only less unique than his earlier childhood, but, not surprisingly, also makes for less scintillating reading.

Shteyngart’s downward spiral was finally arrested in his late 20s when a mentor insisted he start psychoanalysis. Twelve years of intensive therapy gained him the perspective to turn “the rage and humor that are our chief inheritance” into literature – and, with this memoir, correct the “unfaithful record” of his life presented in his novels.

Readers eager for Shteyngart’s trademark caustic humor need look no further than the captions under family photographs, including this howler: “To become a cosmonaut, the author must first conquer his fear of heights on a ladder his father has built for that purpose. He must also stop wearing a sailor outfit and tights.”

There are amusing riffs on his mortifying circumcision at 8, and on his name, a Sovietized version of the German Steingarten, or Stone Garden, which was actually Steinhorn before a slip “in some Soviet official’s hand, a drunk notary, a semiliterate commissar, who knows.” His given name was changed to Gary when his family decided Igor evoked Frankenstein’s assistant.

Shteyngart paints a sharp picture of the Soviet-Jewish immigrant experience, but more personally, a devastatingly tricky portrait of his parents that is at once wince-worthy, guffaw-inducing – and soberingly sympathetic. There are scenes that channel Woody Allen and Philip Roth, including a birthday dinner at his mother’s favorite restaurant atop the Marriott Marquis in Times Square. His parents, who had not read his latest book, deliver a running tear-down that includes this gem: “I read on the Russian Internet that you and your novels will soon be forgotten.”

If Shteyngart left it at this, “Little Failure” would add up to little more than a comic’s bitter shtick. But he goes much further, including a trip back to St. Petersburg (formerly Leningrad) with his parents in his quest to understand where they came from, both literally and emotionally.

He considers the hardships of Hitler’s 871-day siege of Leningrad, during which 750,000 civilians died, many of starvation, and touches on the routine postwar deprivations of Soviet life. His father dreamed of becoming an opera singer but instead settled for a career in engineering – a deep source of frustration, which he took out on his son by belittling him and, later, his achievements.

After the family finally leaves the USSR in 1979 in a trade deal, which Shteyngart amusingly summarizes as grains-for-Jews, there are hardships aplenty, but also miraculous revelations such as steroid inhalers for asthma, bananas in winter, and toilet paper.

There’s no joking about his love for his paternal grandmother, his beloved Madonnachka Polya, who sustained him during tough years when his unhappy parents were cursing at each other, and his father and classmates were beating up on him. In fact, a recurrent, baldly confessed worry is, “Will someone other than Grandma ever love me?”

He deftly weaves his parents’ understandable anxiety about the memoir he’s writing into the book. “Just don’t write like a self-hating Jew,” they admonish him repeatedly.

“Little Failure” is the sort of book usually put off until after one’s parents are gone. But Shteyngart’s driving motivation is in part to show his parents who he really is, and how wrong they have been about him. His readers know that already.

Heller McAlpin regularly reviews books for the Monitor, NPR.org, and The Washington Post, and writes the Reading in Common column for The Barnes & Noble Review.