Can't and Won't

Loading...

This could be a “story” in Can't and Won't.

I wanted to title my book of stories “Can’t and Won’t,” but I thought that when a prospective buyer went to a bookstore and asked for it the clerk would think the customer was asking for “Kant and Wundt,” a substantial tome of philosophy and psychology. I didn’t like that. But then I thought it was more likely the clerk would think the customer was asking for “Cant and Wont,” a light book of empty language and habitual behavior. I liked that, so I titled my book of stories “Can’t and Won’t.”

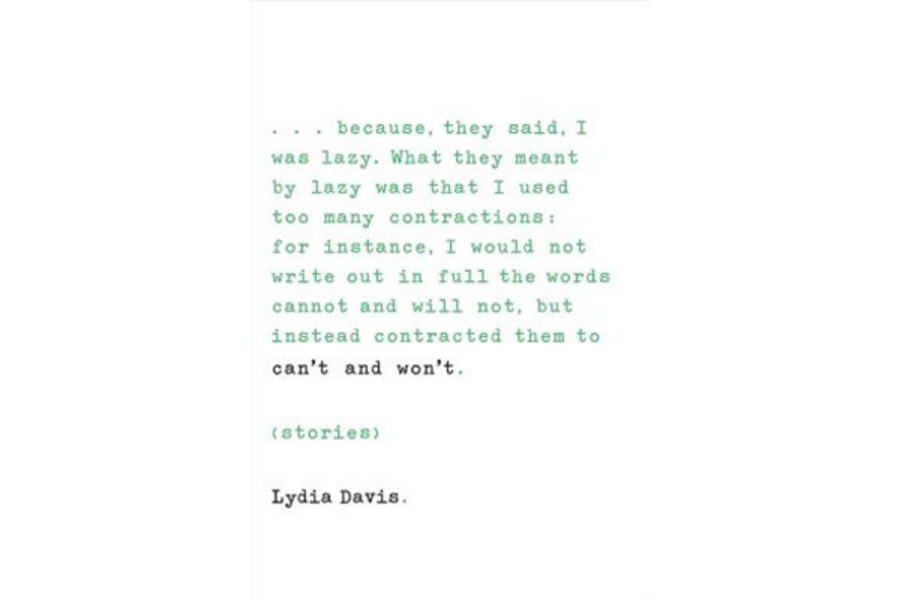

I think his “story” is just as plausible as Davis’s two-sentence title piece in which a narrator says he or she was denied a literary prize because the committee found him or her “lazy” for using contractions such as “can’t and won’t.” My Davis “story” is somewhat longer than her Davis “story” and many of her shorts, and mine has more character development, action, and attention to setting than some. She rarely refers to high culture figures, but the self-consciousness and self-reference, the instability of mind and meanings, the general poverty of diction and lack of metaphor, the repetitive sentence structure, the circular movement, all giving the sense that language might be machine generated, are characteristic of Davis. Also representative are the possibly disarming admission that she customarily produces banalities and the clearly misleading assertion that she writes “stories.”

And yet now seems Lydia Davis’s moment. Last year Davis won the Man Booker International Prize and received an Award of Merit medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. This new collection occasioned a recent New Yorker profile and bears blurbs by James Wood, Ali Smith, Colm Toibin, and Ben Marcus who sound as if they were writing under the influence of laughing gas. The momentum toward this moment began when that most literary of presses, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, published Davis’s "Collected Stories" in 2009. After reading "Can’t and Won’t," I went back to that book. I won’t claim I found the patience to read all 733 pages, but I did survey the kinds of “stories” in the whole and did read the 200-plus pages from "Varieties of Disturbance," which was published in 2007, to see if this new book displays changes in method or achievement from her most recent work.

“Let be be finale of seem,” says Wallace Stevens in “The Emperor of Ice-Cream.” Davis is celebrated for eschewing or mocking all those old-fashioned fictional conventions of “seem”: words artfully arranged, characters that appear to be people, passages of discourse that seem to be conversation, pages that might be mistaken for a narrative. She is the Empress of Ice-Cream, queen of transient small pleasures served cold. In "Can’t and Won’t" the Empress is barely clothed with her short shorts. The most distinctive and remarked on feature of Davis’s work, these one-sentence or one-page “stories” occupy a larger proportion of "Can’t and Won’t" than of the "Collected Stories." Perhaps encouraged or emboldened by her praise and awards, Davis has given over a third of her new book to her briefs. Here is an example, the whole of “Bloomington”: “Now that I have been here for a little while, I can say with confidence that I have never been here before.” Here is all of her final piece entitled “Ph.D.”: “All these years I thought I had a Ph.D. But I do not have a Ph.D.”

I do have a Ph.D., so I’m familiar with Davis’s few learned references in the collection, including Maurice Blanchot and Raymond Queneau’s "Exercises in Style," which tells one story in 99 different ways. I’ve read Stein’s prose poems in "Tender Buttons." I know the B-list of experimental short fictioneers – Beckett, Borges, Barthelme, Barth – and Russell Edson (an early influence on Davis), as well as some of the literary theorists who replaced “story” first with “fiction,” then with “text,” and now maybe with “verbal artifact.” I get Davis’s tradition, but my tolerance for the inconsequential – texts for nothing and about nothing and eliciting nothing – is limited, though I recognize that “stories” of the kind I have quoted and invented could be ideal reading for cell phones. Or the texts could function like bread between wine tastings, but too many of Davis’s shorts – really “tinies” – come one after another, page after page of eked words, white space, and inconsequence. In "Can’t and Won’t," less is least.

Davis may be a little nervous about the increase of shorts because she uses her last page to explain what she’s doing in two kinds of brief “stories” not found in "Varieties of Disturbance." Many of the new one-page pieces are labeled “dreams.” Davis says some of them were contributed by others and some were her own. Though presented as a stickler for precision in her profile, Davis fails to note that the “dreams” are not, in fact, dreams but verbal accounts of dreams and probably selective accounts at that. That is, they are fictions. I know people who skip over dreams in novels. The temptation is strong in "Can’t and Won’t."

Some other one-page pieces are called “stories from Flaubert” and are “formed from material found in letters” written by that novelist. How much credit for these appropriated anecdotes should go to Flaubert and how much to Davis is impossible to tell. Perhaps weary of invention, Davis has decided to put others’ words in her work. A third kind of short in "Can’t and Won’t" can be called, after the following “Housekeeping Observation,” observations: “Under all this dirt the floor is really clean.” This one happens to be more koan-like than most. Try meditating, for example, on this geographical observation: “She thinks, for a moment, that Alabama is a city in Georgia: it is called Alabama, Georgia.”

With “Dreams,” “Flauberts,” and “Observations,” Davis is using slightly different methods from her recent work to test just how much inconsequence readers will accept. For most writers, the items in all three groups would be confined to their notebooks for possible use in or development to stories. For Davis, the pieces are “stories.” Perhaps together they even trace the development of story from Flaubertian anecdote to modernist surrealism to postmodernist whatever. Individually, though, the pieces pretty much flatline, with a few blips of faint wit, on the consequence monitor. However, if you find the works I’ve quoted subtle or profound or humorous, you need read no further. Get thee to a bookstore and carefully pronounce "Can’t and Won’t."

Davis’s stripped approach in the one-liners or one-pagers carries over to the less short or little longer texts, which also fall into several categories. There are lists: of numerous items the narrator doesn’t find interesting or does find interesting in the Times Literary Supplement, many things that make a narrator uncomfortable, characteristics of a cat named Molly, the sounds of objects in a house, and “Local Obits,” one or two sentences of life summaries found in obituaries. Like the very existence of the shorts, the items seem arbitrary. They form a series rather than a sequence, the origin of “consequence.” Some other texts are “Travel Observations.” A narrator, possibly the same narrator since Davis pays scant attention to different voices, is traveling by train or plane and observes the passing scene and other people. Because the narrator is moving, the pieces can be called sequences or narratives, though usually not moving narratives because the route is fixed and the style is generally affectless.

"Varieties of Disturbance" has only two lists and two travel stories, so with "Can’t and Won’t" Davis is amping up arbitrariness and, to my mind, damping down significance. But among her mid-length pieces is a heretofore little used mode – the faux letter – that generates more interesting work. The letters are addressed to manufacturers of frozen peas and candies, a bookstore manager, a “Biographical Institute,” and to a foundation. In these, Davis shifts from her wonted reduction of means to compulsive elaboration, and the texts begin to have the weight of stories. The letters begin with modest purposes – to complain, correct, or inform – but a scrupulous or manic desire to explain extends the missives far beyond their initial goals to revelations about the person writing and, in the 28-page letter by a professor to a foundation, to a sad and comic commentary on academic life. But missing from almost all the mid-length pieces, even from letters addressed to a named recipient, is human reciprocity. The Empress observes and thinks and sends messages but has no use for dialogue.

The most substantial pieces in "Can’t and Won’t" are essentially meditations but can be safely termed stories. They are consequential because thoughts or actions within them have consequences for their characters and because the stories could have more than a transient effect on the reader’s consciousness. "Varieties of Disturbance" has quite a few such stories. In "Can’t and Won’t" they number only three – the letter to the foundation and two with animals in their titles. In “The Seals” the narrator remembers her dead sister, the complications she caused, and the narrator’s ambivalences toward her. “The Cows,” my favorite, could be called, after Wallace Stevens, “Eighty-nine Ways of Looking at Three Cows.” Watching cows from various perspectives in or near her home, the narrator learns about them and about how her mind and feelings work. Although lacking the emotional tug of “The Seals,” “The Cows” could very well be a perceptive epistemological exercise. Or I could be desperate to say something complimentary about Davis’s work.

Towards the end of "Can’t and Won’t," yet another category not so explicitly present in "Varieties of Disturbance" emerges: metafiction. Two one-page pieces advise revisions of works we don’t see, and somewhat longer texts called “Writing” and “Not Interested” are comments on reading. Since I have that Ph.D., I would never be so naïve as to think the narrator of these last two is Lydia Davis, but some of the remarks might be construed as a rationale for the kind of fiction Davis has always done and is now doubling down on. (Maybe that last phrase should be “halving down on.”) In “Writing,” the narrator complains, “Writing is often not about real things.” The narrator of “Not Interested” says, “These days, I prefer books that contain something real, or something the author at least believed to be real. I don’t want to be bored by someone else’s imagination.” “Let the lamp affix its beam,” says Stevens in “The Emperor of Ice Cream.” No more illusions, no further imaginaries. Although I can invent such stuff, the Empress suggests, I won’t.

But ontologically (if I may) the naked sentences and arbitrary texts in "Can’t and Won’t" “contain” no more of the “real” than traditional stories. If the texts look too dumb to have been invented or appear to be autobiographical or even if the author uses her own name within a piece, as Davis does in several, the reader still can’t know that the text is “real,” that it is true and not a fiction. Like the first novels in English, Davis’s writings do sometimes resemble documents – scholarly studies in "Varieties of Disturbance"; lists, letters, medical records, and obituaries here – found in the real world, but that doesn’t mean her works are therefore found objects. Her texts are imitations of real documents, just as written stories are imitations of real oral storytelling. Books like Davis’s may seem to offer raw truth, but they have been cooked, if only slightly or badly.

“It seems a country-headed thing to say,” said William Gass many years ago, “that literature is language, that stories and the places and the people in them are merely made of words.” Since both conventional stories and Davis’s texts are word-made imitations, the evaluative question for me is consequence. The narrator of “Not Interested” is easily bored by “good” novels and stories. The writers who so hyperbolically praise Davis in her blurbs are probably also bored by traditional fiction, no matter how “good” or skilled or imaginative it may be. David Shields in "Reality Hunger" – which, perhaps not coincidentally, praises Davis and carries a blurb from her – is the spokesmen for those who suffer from Fiction Attention Disorder, readers sated and jaded by artists’ imagination and art. F.A.D. makes Shields susceptible to faddish “reality” writing akin to reality television. Examined with even a little rigor, Shields’s arguments against fiction turn out to be rationalizations for the confessed narcissism from which he has constructed a career. Me, I’m bored by banalities and irritated by trivialities that an author implies are mysteriously consequential because “real” and because included in a printed book (not just broadcast into the Twitterverse). I’m not against real life in life, but in language my hunger is for profundity or ingenuity or subtlety or, better yet, all three in a single work.

I believe Davis is having her moment now because every decade or so a writer emerges – a Burroughs or Barthelme or Carver in America – who seems to be cleansing the palate of fiction with the “real” and causing cognitive dissonance with an unconventional style. “Seems” because I think actual cognitive dissonance is created by works such as Atwood’s "Alias Grace," which mixes historical facts and invention, or Mark Z. Danielewski’s "House of Leaves," which combines real documents and the fantastic. Davis’s dissonance is easily “recuperated,” as the theorists say. She doesn’t really threaten and does no harm.

The Empress is becoming more insistent on inconsequence but issues no ukases. Lydia Davis doesn’t pretend to be anything she’s not. No, it’s writers like Shields and her other boosters who make extravagant and, ironically, unrealistic claims for her fiction who have no clothes. Could I be the Emperor? It’s possible, but until I get more from Davis I’ll keep thinking of myself as Stevens’s “Snow Man,” who sees “Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.