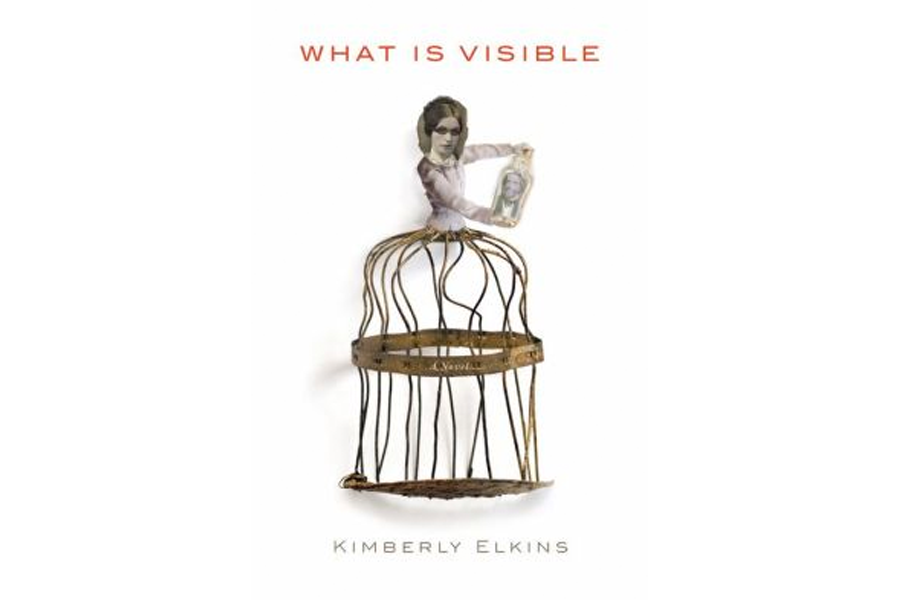

'What Is Visible' is based on the true story of Laura Bridgman who, before Helen Keller, communicated without hearing, sight, or speech

Loading...

Before Helen Keller, there was Laura Bridgman.

Scarlet fever not only robbed the 19th-century New Hampshire girl of hearing, sight, and speech at the age of two, it also took her sense of smell and taste, Kimberly Elkins writes in her debut novel, What Is Visible, which hopefully will restore Bridgman to at least a portion of the popularity she enjoyed in life.

When she was young, Bridgman was considered the most famous woman in the world after the Queen of England. And in the novel, the fictional Laura combines the innate hauteur of an aristocrat with the longing of a lonely girl to be loved. Her intelligence was too prickly and her will too imperious to suit the Victorian mores of the time, but both combine to make her unforgettable. And, given that she was locked alone with her thoughts most of the time, Laura’s self-centeredness is completely understandable.

“What Is Visible” opens with two historic meetings. The first is in 1888, during the real-life meeting between Keller and Bridgman, when the former was still a little girl. "There is no record of what transpired at the meeting between Laura and Helen, save the fact that Helen stepped on Laura’s foot,” writes Elkins in an afterword.

Annie Sullivan urges Laura to talk to Helen, saying that the two have so much in common. “Like two in the throes of the plague might share tips and grievances?” Laura thinks acerbically, before commenting on how soft Helen’s hair is.

“I didn’t like children even when I was one, and now I think them worse than dogs,” she thinks. “I’ve shriveled and so they’ve searched for another freak in bloom to exhibit and experiment on. It’s taken Perkins decades to find one pretty enough, quick enough. Well, pretty is really the important thing, or at least not too strange or looking like what she is. Not looking like what I am.”

The novel then jumps back to the 1840s when Laura was the official face of the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, which was established in 1829, the same year she was born. On that day, the 12-year-old, who was regularly paraded out during Saturday Exhibition Days, is presented to Charles Dickens, who likens her to Little Nell. (What a stupid name, she thinks.) Laura is on her best behavior that day – writing on a chalkboard when asked, finding London on a globe, talking with the famous writer by fingerspelling into his hand and giving him a needlework purse she made as a present for his wife. In return, Dickens’ account of her in “American Notes” ends up making her a celebrity.

“The good thing – probably the only good thing – about writing in someone’s hand instead of speaking is that no one can eavesdrop. I don’t know how regular people manage to have any secrets,” she says.

In fact, all the sighted people surrounding Laura are harboring at least a few, some of which do blow up in their faces during the course of the novel. In “What Is Visible,” Laura shares narrating duties with her teacher and companion, the director of the school, and his new wife.

Laura’s beloved Doctor, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, is about to have a lot less time for his most celebrated pupil. Howe, Perkins’ first director, brought Laura to the school when she was seven, showing her how to communicate with the outside world. His work with Laura is credited as the first time someone succeeded in teaching language to a deaf-blind person.

Unfortunately, “What Is Visible” completely skips over what learning to read and write would have meant to Laura, who before she came to Perkins was reduced to communicating by tantrums and having her family push her where they wanted her to go. By the time the novel opens, Laura has become so famous that dolls of her are sold all over the country, “with their eyes poked out and little green grosgrain ribbons tied over the eyeholes,” Laura recounts proudly. (The money from the sale of these 12-inch-tall creepy models of exploitation go to the Perkins school – not Laura. She is, however, allowed to keep the proceeds from the sale of her needlework purses.)

Howe’s fiancee, Julia Ward, would become best known as the writer of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and – ironically enough given the aversion to parenting she displays in “What Is Visible” – the inventor of Mother’s Day. But the future writer and suffragist started out as one of the two Ward sisters, who were celebrated for their beauty and inheritance.

As if Keller, Dickens, Sullivan, and the Howes weren’t enough real-life personalities to fill one novel, the crusading journalist Dorothea Dix was a champion of Laura’s. Howe was friends with poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Sen. Charles Sumner, a champion of public education, prison reform, and ending slavery and segregation, whose abolitionist views would cost him a famously vicious beating on the Senate floor. Sumner is a frequent visitor to the Perkins School, where, despite his admitted brilliance and lofty ideals, neither Julia nor Laura regard him favorably.

While the two probably could have been great allies, Laura is too jealous and Julia, somehow, can never quite muster the empathy Laura’s lonely condition should inspire. Both, ultimately, fall short of Howe’s expectations for their conduct: He is the “Paragon of Noble Usefulness,” as Dickens styles him, and will graciously bask in their adoration. They will be dutiful dolls.

To be fair, during their engagement, Howe does warn Julia that, unlike Shakespeare, “I don’t want a marriage of two minds, my darling…” Instead of hitching up her silken skirts and running for the hills, Julia, a spoiled heiress, simperingly agrees to everything and plans to go behind his back to write. (She assumes that her husband, like everyone else always has, will ultimately give in to her wishes.) One of the most sympathetic scenes of the novel is when Julia sneaks a child’s desk up to the attic, so she can write.

Poor Laura, a skinny adolescent who no longer fits on Howe’s lap, is simply left behind. After teaching her to communicate, Howe has no interest in what she has to say. She is no longer a cute prodigy – or content to be spoon-fed whatever bits of theology and knowledge Howe deems suitable. To punish her, the school would “glove” her, denying Laura her sole means of contact with the outside world. Howe then tosses her back to her family in New Hampshire, who neither want her nor know how to care for her. After Laura nearly starves to death, Howe brings her back to Perkins, possibly mindful of the negative publicity the school would suffer if its star pupil died of neglect. (It is highly unlikely that Perkins, which is still operating today, will view Elkins’ portrayal of its first director at all favorably.)

While she seems to delight in knocking celebrated men and women off pedestals and pointing out the cracks in their marble likenesses, Elkins hews closely to the historical record for most of the novel – even a marriage that leads one of Laura’s teachers to Hawaii (then the Sandwich Islands) has its basis in fact. There is one notable exception: Elkins invents a sexual affair for Laura that she acknowledges almost certainly never occurred. (It might be possible that a 19th-century kitchen worker was literate enough to communicate with Laura through fingerspelling, but it doesn’t seem likely.) What is completely believable is that Laura, who was isolated from all but a few, would form passionate attachments to anyone who could communicate with her.

The novel takes its title from something Laura says at the end of the novel: “I am denied the pleasure, or pain, of ever being able to read my own words. You will be able to read them, but I will not. So I write this out into the air, in a grand and looping script, that what is invisible to man may be visible to God.”

Laura says she hopes that her public presentations “show how little one can possess of what we think it means to be human while still possessing full humanity.” “What Is Visible” certainly succeeds on that score.

Yvonne Zipp is the Monitor's fiction critic.