'Boy on Ice' tells the sad story of the rise and fall of an NHL enforcer

Loading...

If it weren’t for fighting, he would never have made it to the NHL.

Derek Boogaard was born in a small town in Saskatchewan, Canada, home to some of the toughest hockey players around. Boogaard was clumsy, couldn’t handle a puck, and had no skill on the ice. But he was big. By 12-years-old he was already more than 6 feet tall, dwarfing other players. Most coaches kept Boogaard on the bench, and when he made it to the ice, parents would make fun of his awkwardness.

It wasn’t until Boogaard tried to fight an entire team that a hockey scout saw potential. Boogaard, then 15, became so enraged during a game that he jumped into the opposing team’s bench and hit anything in his path. Most sports leagues would suspend players for such violence, but in hockey, it gives players a bright future.

Taking on the unofficial position of enforcer, Boogaard's job was to protect star players from dirty play. The 6'8" Boogaard wasn't expected to score goals, he was expected to fight – something at which Boogaard really excelled. Boogaard was feared by opposing players and loved by fans, and as an enforcer for the Minnesota Wild and the New York Ranger, he used his fists to quickly become one of the scariest names in the National Hockey League.

But his duties as enforcer took a toll on Boogard's body, leading to concussions, drug addiction, and chronic pain. And eventually the role killed him.

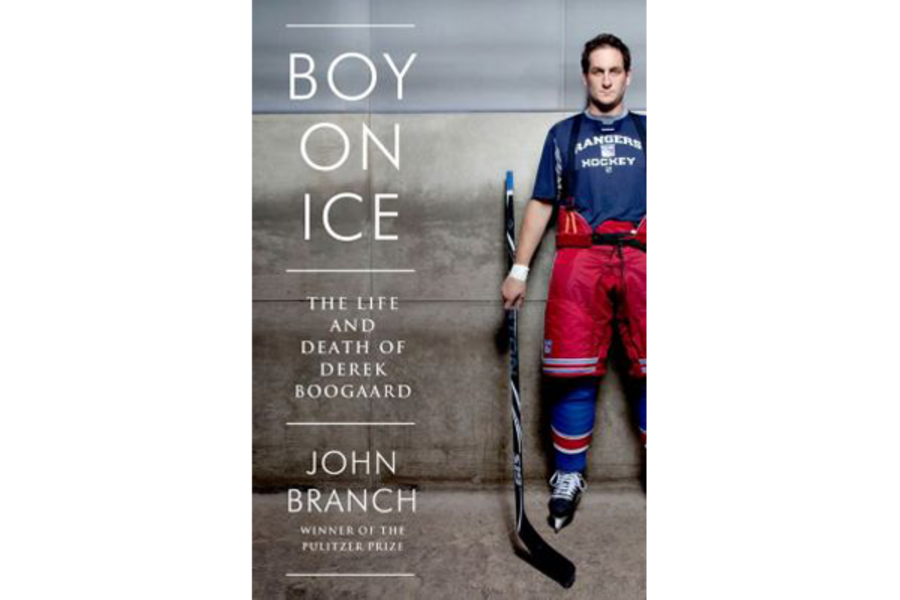

Boy on Ice: The Life and Death of Derek Boogaard by John Branch explores the rise and fall of the NHL enforcer. Branch is a sports reporter for The New York Times and is best known for his Pulitzer Prize winning story “Snowfall.” "Boy on Ice" is an expanded version of his 2011 series “Punched Out,” which includes a 37-minute interactive video. “Punched Out” was awarded the Dart Award for Excellence in Coverage of Trauma, and was a finalist for the 2012 Pulitzer Prize in Feature Writing.

The book is meticulously reported and beautifully written. Branch, well known for his deep investigations, interviewed all of Boogaard’s family and friends, and gave readers a peek into the enforcer's thoughts using 16 pages of notes written by Boogaard.

The book explores the systemic culture surrounding fighting in hockey, from youth rinks to professional leagues, as well as the rise of the role of the enforcer. Enforcers became popular in the late 1980s when teams needed someone to protect star players and to intimidate the other team. Enforcers were big and spent more time in the penalty box than on the ice.

“When the enforcers fought, the game clock stopped. Other players, restricted by stricter rules, barring entry into the fight, backed away and watched. Fans, invariably stood and cheered, often more vociferously than when a goal was scored,” Branch writes in the book.

From a young age, Boogaard was groomed to be a fighter, but – as has been the case with other enforcers – the years of fighting took a toll on both his body and his psyche. Fighters are only as good as their last fight. One loss could cost them their job. Because of the insecurity, fighters must fight through pain. To deal with his pain, Boogaard turned to medication, which landed him in rehab. And the constant hits to his head seem to have impacted his brain.

Reading this book, one cannot help but ache for Boogaard who was described as meek and quiet when he wasn’t fighting on the ice. It appears that he never really wanted to be a fighter, but saw fighting as his only pathway to a place on a team. He was a victim, it would seem, of his size and hockey culture.

The book adds to the conversation professional sports leagues, like the National Football League, are having about the dangers of repetitive brain trauma. After his death, Boogaard’s brain was taken to Boston University’s Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy Center. When researchers looked at Boogaard’s brain, they reported a finding of advanced CTE. The condition has also been found in other athletes who sustain repetitive hits to the head.

In some respects, the material in "Boy On Ice" worked better as series of articles than it does as a book. Boogaard was not a noteworthy enough NHL player to merit an entire biography. The first hundred pages of the book, chronicling his early life, is probably more information than most readers will want. And if fighting turns your stomach, this book isn’t for you. The scenes detailing violence on the ice are frequent and protracted.

But, for hockey and non-hockey fans alike, "Boy on Ice" carries an important message. It is an honest account of the life of an NHL enforcer, and demonstrates the toll that years of fighting and concussions can take on a player who accepts such a role.