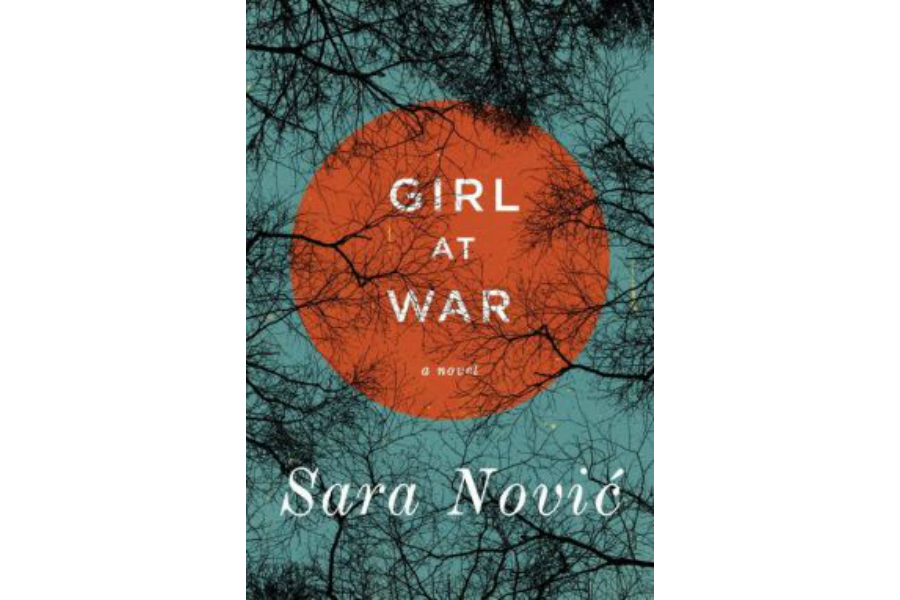

'Girl at War' unravels a heart-rending story on war and identity

Loading...

Google the words “Balkan Conflict” and the Internet drops you down a rabbit hole. Empires rise and empires fall. Amid a crazy quilt of ethnicities on the Balkan Peninsula, the modern-day nations that ascend remain as powerless as their predecessors to rein in the factions willing to spill blood in a quest to lay claim to their homelands. Through this revolving door of conquerors and the conquered comes Sara Nović with her debut novel, Girl at War. Set during and after Croatia’s War of Independence, it’s a slender thread of narrative freighted with centuries of history.

It’s 1991 when we meet Ana, a lively 10-year-old living with her parents and her ailing infant sister in Croatia’s capital city, Zagreb. Ana’s a tomboy who, along with her best friend, Luka, has the run of the city. The civic fissures that are the first signs of the political fragmentation of Yugoslavia have begun to affect daily life, and rumors that the Serbs have blocked the roads from Zagreb to the Adriatic prompt Ana’s father to cancel the family’s annual seaside holiday. Instead, Ana and Luka spend their time bicycling through their corner of the city, where escalating tensions between Croats and Serbs become apparent even to the children.

One morning at the town square, the usual bustle has a strange, anxious energy. Edging closer, Ana and Luka see that at the center of the milling crowd is an encampment of refugees who have fled the fighting to the east.

"The settlement was made almost entirely out of string. Ropes, twine, shoelaces, and strips of fabric of various thicknesses were strung from tractors to piles of luggage in an elaborate tangle. The strings supported the sheets and blankets and bigger articles of clothing that served as makeshift tents."

Unsettled by the sight, Ana makes Luka shove some coins into a “Help the Refugees” collection box and then, gut-punched by how wrong it all feels, the duo hop on their bikes and flee. Back home, meanwhile, Ana’s baby sister, Rahela, is getting sicker. Her kidneys are failing, and a trip to the United States for emergency treatment is the only way to save the infant’s life.

Amid air raids, food shortages, and the aerial bombing by the Yugoslav air force of the official residence of the president of Croatia, Ana’s family undertakes a road trip to Sarajevo to deliver Rahela to the foreign aid group that will send her to Philadelphia for medical care. On the drive home from Bosnia to Croatia, another Serbian roadblock changes Ana’s life again, this time forever.

With "Girl at War," Nović tries to make sense of what happens after a child survives the worst that life can throw at her. Following the harrowing scenes at the roadblock, Nović jumps the story forward ten years and sends Ana, now twenty, to college in New York. Ana’s sister, now known as Rachel, is a healthy and thriving American girl with no memories of her previous life.

Although Ana has grown up with the same adoptive parents as her sister, she remains a stranger to her new family, to her new country, and to herself. She’s an insomniac who lies to friends about her origins, is both a cynic and a skeptic during a speech she gives to the UN, and can’t make sense of, let along make peace with, her past. After 9/11, as the U.S. attacks in Afghanistan and Iraq, the profound disconnect between what Ana knows of war, and the American experience of it, eats away at her.

"But America’s war did not constrain me; it did not cut my water or shrink my food supply. There was not threat of takeover with tanks or foot soldiers or cluster bombs, not here. What war meant in America was so incongruous with what had happened in Croatia — what must have been happening in Afghanistan — that it almost seemed a misuse of the word."

The challenge with a character this damaged and closed off, though, is letting the reader in enough to care. Nović’s nuanced portrayal of Ana as a child is just lovely, filled with grace and warmth and depth. It’s in the flash-forward to adulthood that the story falters. Ana’s an adult, a stranger to us now. Due to the novel’s time-tripping structure, crucial gaps in her history have yet to be filled in. Instead of damaged, Ana comes across as petulant, and with surliness standing in for trauma, goodwill gets squandered.

It’s fitting, then, that when Ana returns to Croatia in search of answers, Nović regains her balance. Scenes of unexpected culture shock, of not-American Ana realizing she’s not quite Croatian either, have the stamp of truth. Girl at War brings the story around full circle, and in the same places that Ana lost her life, Nović gives it back.