'Krazy' adds further luster to the legacy of 'Krazy Kat' creator George Herriman

Loading...

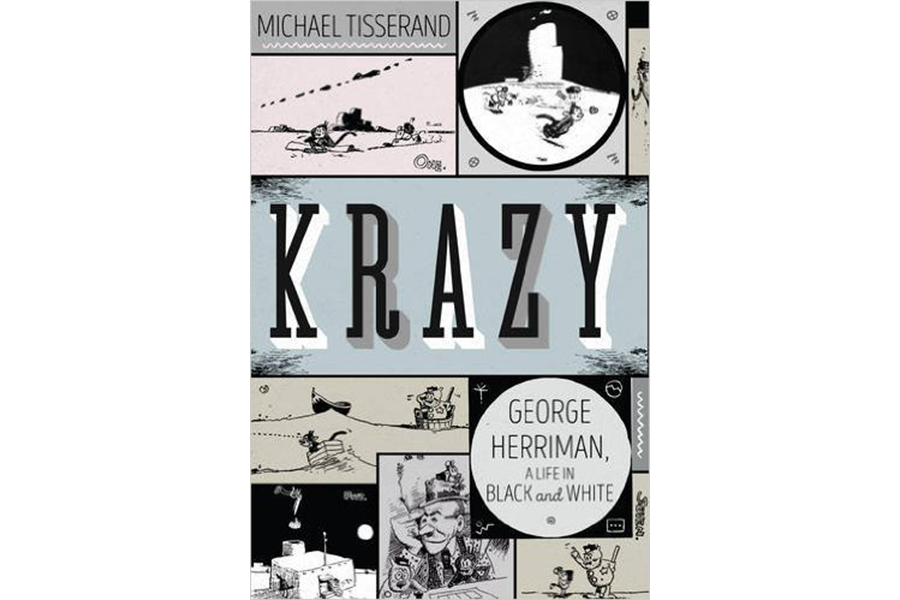

When asked about powerful influences on their own work, some of the 20th century's most prominent cartoonists, people like Calvin & Hobbes creator Bill Watterson, Doonesbury creator Gary Trudeau, and even the great Will Eisner invariably credit one name in common: George Herriman, who gets a splendid, sympathetic full-length biography – his first – in Michael Tisserand's new book Krazy: George Herriman, A Life in Black and White.

Herriman was born in New Orleans in 1880 (to mulatto parents, which set up in his life an undercurrent of racial tension Tisserand depicts with refreshing sensitivity), showed early promise as a creative illustrator and writer, and entered the world of cartooning just as it and the 20th century were beginning. He plied his pen and brush for a host of paying clients, and the sheer amount of archive-combing work his biographer has done to find traces in a profession of ephemera is mind-boggling. Tisserand tracks Herriman from project to project, giving readers a surprisingly exciting picture of a talent steadily maturing, with signs of genius showing as early as 1909 in a strip called Baron Mooch, which was, we're told, “Herriman's most outlandish all-human strip, the first sustained visit to the outer reaches of his imagination.”

Of course Herriman's claim to immortality lies with a later creation, the lovelorn dreamer Krazy Kat and the brick-hurling object of his affection, the irascible mouse Ignatz. The two first appeared as recurring visual gags in The Dingbat Family, a strip Herriman was doing for the Evening Journal in 1910. “In each panel the mouse creeps closer,” Tisserand writes. “Then, without provocation, the mouse picks up a tiny object, takes aim, and launches it at Kat's head.… A new battle had begun.”

The characters later starred in their own strip, and right from the beginning, there were fans who appreciated the work Herriman was doing – and the boundaries he was pushing. The free-flowing nature of that work – as Tisserand aptly puts it, “improvisation was central to his craft” – is a difficult thing to capture in prose, and this biographer surely does it about as well as it can be done, taking readers inside the constantly-shifting landscapes of Herriman's work at its peak. “A conversation starts with Krazy and Ignatz first strolling on farmland, then into a dark tunnel, then floating in a pool of water, then hiking up the side of a mountain,” Tisserand writes. “They recline on cannonballs as they are fired; they lie together in bed. They are targets in a carnival game, talking about death.”

Unlike some of the other virtuoso cartoon strips of later decades – Hal Foster's Prince Valiant comes to mind – Krazy Kat struggled to find widespread popularity, which is the main reason Herriman's work today is mainly known by connoisseurs. Luckily for the artist, one of his earliest and strongest admirers was in a perfect position to express that admiration: he was newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, and he soon gave Krazy Kat new larger graphics layouts that were perfect for the kinds of visual experimentation Herriman wanted to do. “One day readers might behold a densely packed series of irregularly shaped panels that track Krazy's plummet over a waterfall,” Tisserand writes. “On another, a tale of a lost Ignatz opens with a long, horizontal desert vista.”

When it comes to discussing Herriman's work, Tisserand is a model of balanced perspective, neither overpraising the artist's B-side juvenilia nor ranking his greatest work alongside the invention of penicillin. Krazy is an engrossing portrait of an artist hard at work in a busy era, with penny-pinching patrons and fast-hustling colleagues crowding the tables at restaurants in New York and Los Angeles. And through it all, Tisserand keeps Herriman himself thoroughly, accessibly human. The artist was generous, caring, and universally beloved, although as becomes clear throughout the book, he could be his own harshest critic. As fellow cartoonist Charlie Plumb put it, “Herriman has the biggest inferiority complex in the craft; you could pile all the bricks that Ignatz ever threw at Krazy and not fill it up.”

Herriman died in California in 1944, and Hearst retired Krazy Kat rather than farm it out to a succession of imitators. This decision added to the iconic status the strip would have had in any case, and Michael Tisserand has now given readers a wonderful companion volume to that iconic artwork. The poet Carl Sandburg, a big fan of Krazy Kat, once thought to go and visit the artist and then changed his mind, telling himself, “Hell, he can't tell me any more than what it says there in his work.” But "Krazy," so rich in anecdote and so warm in affection, succeeds in adding a good deal to the wonder of George Herriman's legacy – mainly by putting the artist in last place on Earth he liked to be: in the spotlight, center stage.