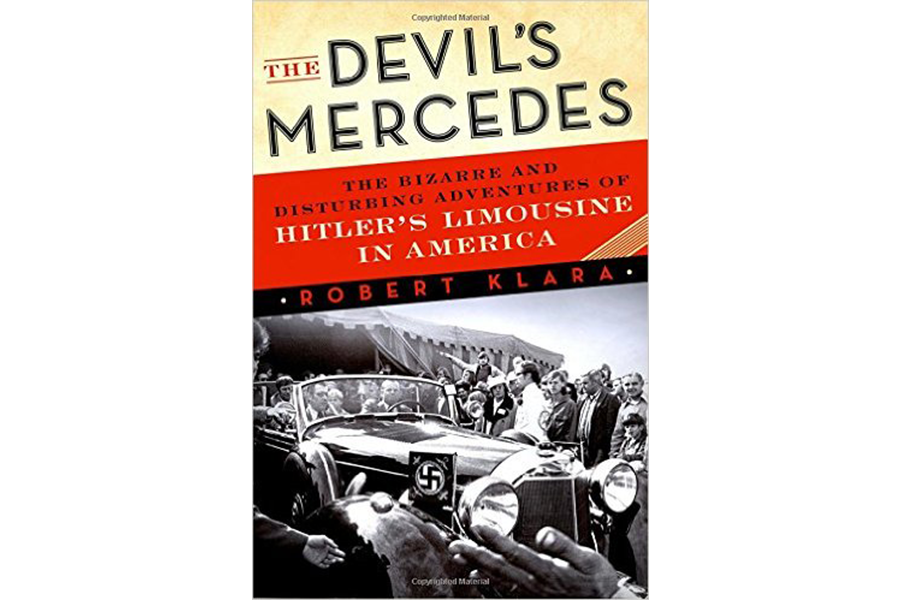

'The Devil's Mercedes' investigates a pair of notorious Nazi limos

Loading...

Last month, a worn, rotary dial telephone once owned by Adolph Hitler sold for nearly $250,000 at a small auction house in Chesapeake City, Maryland. The auctioneers modestly described the device as “Hitler’s mobile voice of destruction.” At the same auction, a porcelain figure of an Alsatian dog, also owned by Hitler, was sold to a different bidder for $24,000. Perhaps not surprisingly given that the previous owner was a genocidal madman, neither of the purchasers wanted to be identified.

None of this would surprise Robert Klara, the author of The Devil’s Mercedes: The Bizarre and Disturbing Adventures of Hitler’s Limousine in America.

Klara’s tale is not about a telephone but rather two cars that were indisputably associated with the Third Reich. These were not just any cars: Both were 1941 Mercedes Benz Grosser 770 K model 150 open touring cars that had been used to ferry the Nazi elite.

With good reason, one owner called his car “the Beast.” Each was nearly 20 feet long, armor-plated and equipped with thick bullet proof glass, weighed five tons, could reach speeds of 100 miles per hour and burned a quart of oil every 65 miles. According to one driver, operating one of these was “like driving a cross between a jet plane, your family bus and Hook and Ladder 37.”

But a major question surrounded both cars – which Nazi had used them?

One of the cars came to the US in 1948 from Sweden as payment for a shipment of ball bearings. The Swedish owner insisted that the vehicle was Hitler’s personal car and so Christopher Janus, a young Harvard educated, Chicago wheeler-dealer became its first American owner. He proudly proclaimed it “Hitler’s car” and used it to raise money for charities before selling it to another collector in 1952.

The second car was captured by an American soldier on a railroad siding in Bavaria. A German mechanic insisted that the vehicle belonged to Hermann Göring and so – with no other evidence – it quickly became known as “Göring’s staff car.” This one – now property of the US Army – was used to help sell war bonds before being placed in storage at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland.

Both cars changed hands multiple times – it turns out that owning an auto that may (or may not) have been used by two of the most notorious and despised human beings of the 20th century generated plenty of controversy and criticism and several owners resold the vehicles very soon after acquiring them.

“Goring’s car” eventually ended up in the Canadian War Museum where it was prominently labeled “Göring's Staff Car” even though there was no evidence to support the attribution. “Hitler’s Car” meanwhile found its way to a classic car collector in California where it was painstakingly restored to its original pristine condition, a process that took almost two decades.

But the ultimate question is whether either car had really been used by Hitler or Göring. Klara quickly establishes that “Hitler’s” limousine was actually a gift from the dictator to Carl Gustaf Mannerheim, the brilliant military leader and founder of modern Finland. Hitler was aware of the car and, apparently, rode in it briefly, but today it is known as the “Mannerheim” Mercedes because it had almost no connection to the Nazi leader.

And there was no proof that the Reichmarshall had ever used “Göring’s staff car.” But a librarian at the museum took a keen interest in the provenance of the limousine and eventually proved that the car had – for almost two years – been used by Hitler himself. So the car that might properly be called “The Devil’s Mercedes” actually resides in Canada, not America. Unlike the other Nazi limousine, this car was not restored.

Ultimately, this engaging and entertaining book is several things. For starters, it’s a little jewel of investigative journalism that carefully traces the path traveled by two massive if utilitarian pieces of machinery over a span of seventy years. Most of all, it’s a great story that features a cast of characters and plot twists even Hollywood wouldn’t dare to invent. Car collectors themselves can be quirky and compulsive and so it’s no surprise that the cars changed hands so frequently and that claims about the vehicles were so fantastic – it comes with the territory and it makes for a great read.

But it’s also a book about how we remember the past. Klara makes clear that even those owners who used the cars to raise money for charity found the psychological and reputational burden of possessing something that was associated with Adolph Hitler was unbearable. When he sees the cars, one significantly deteriorated and the other in pristine condition, Klara admits to a rush of varied and conflicting emotions. And, as he watches other visitors examine the car in Ottawa, he realizes that he is not alone – almost everyone who stops to look reacts in some visible way to a car that is, in fact, “falling to pieces.”

Some seven decades have passed since the Third Reich was so decisively destroyed. And yet, even today, its meaning and legacy is the subject of continued debate and discussion. As painful as such reminders of it might be, they serve as a clear and constant reminder of man’s capacity for evil.