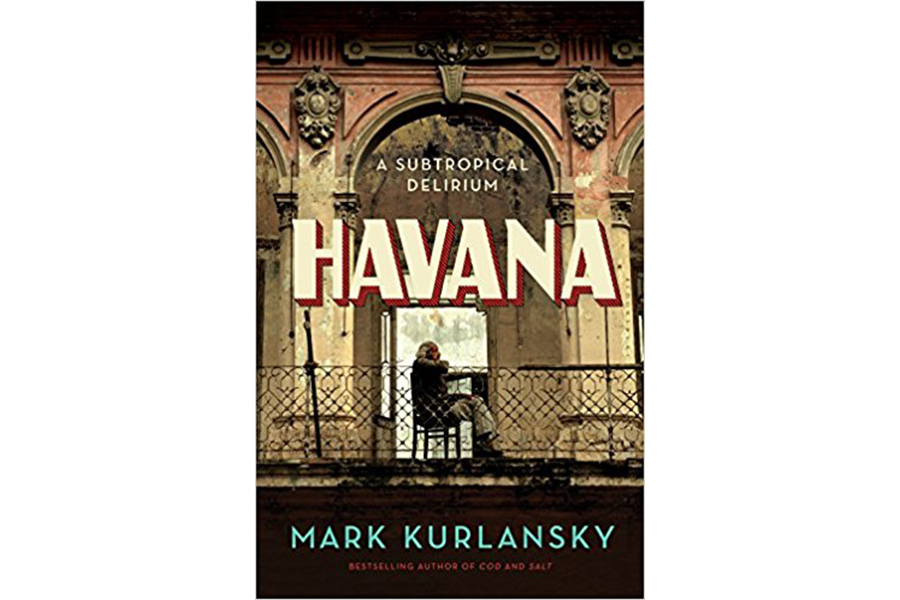

'Havana' probes the mysteries and magic of the Cuban capital

Loading...

Havana, City of Smoke. From peerless Montecristo #2s, if you are a wishful cigar aficionado; from pirate raids repeatedly reducing the city to ashes after plundering its entrepôts of Spanish gold, or – more grimly – from firing squads putting down slave rebellions, if your heart beats to a different drummer. There is the skin-smoking white heat of the sun, coaxing the eternal question Mark Kurlansky gives voice to in his new book, Havana: a Subtropical Delirium: “How can it be so ... hot?” Havana smokes like the best film noir. Smokes in attitude, literature, cinema, its fiery political arguments. It’s smoky from the fumes of living under occupiers, oligarchs, plutocrats, dictators, and ideologues. No doubt the Tainos, the indigenes at the time of European encounter, have plenty to smoke about, if there are any left alive.

Havana, too, is the City of Columns, the Rome of the Caribbean. It’s all in your angle of approach. Drive into town from the airport, and your escorts will be the state psychiatric hospital “and drab, gray buildings, or rust-streaked, turquoise, and rotting pink ones – resembling birthday cakes left out too long.” Come at the city by boat, off the deep blue of the Gulf Stream and into the robin’s-egg and violet waters of the port, and a spell – part intrigue, part eyeful – is spontaneously cast.

These approaches will condition what you experience next. Will the city be narrowly and confusedly congregated or an adventure in exploration? Is the paint dingy or tropical? (Federico García Lorca had no issue: “Havana has the yellow of Cádiz, the pink of Seville turning carmine and the green of Granada, with the slight phosphorescence of fish.”) Is the place a dump or delicately deliquescing? Kurlansky has taken both roads over the last thirty-five years of visits, and his verdict: “Havana, for all its smells, sweat, crumbling walls, isolation, and difficult history, is the most romantic city in the world.” Keep your City of Light, your City of Love, and your Serenissima, too.

As in Kurlansky’s other discerning and obsessive investigations – such as "Salt," "Cod," "Paper," and "The Big Oyster" – the generous historical narrative of "Havana" is sparked by, or sparks, some Technicolor tidbit he has dug up. In "Cod" there were the Irish monks in their coracles – big teacups, but not all that big – floating their way to the Faroes and Iceland, the tonsured ones sustained by dropping a hand into the great sea and simply pulling out readymade sashimi.

In "Havana," that curio might be the nexus of narrow sidewalks and big windows (and street life in general), or the semiotics of shaven ice, the pop-up restaurants now appearing in Habanero homes, or Fidel’s 26 flavors of ice cream (Howard Johnson had 28, but Fidel ate all his at one sitting, according to rumor, a fable that might be read as either heroic or deflating), or the live-and-let-live of perspiration: “Havana is not a city for people who are squeamish about sweat. Sweat is one of the many defining smells in redolent Havana and it is a leitmotif in almost all Havana literature.”

Cuban literature – it takes willpower not to lay aside "Havana" to read one of the many books Kurlansky suggests, with their gritty magic realism/existentialism: Alejo Carpentier’s "The Chase," say, or Cirilo Villaverde’s "Cecilia Valdés," a “condemnation of slavery and slavery’s impact on society.” Contemporary Cuban writers are well in the political mix, where criticism abounds.

So, too, with the cinema taking on the island’s bugaboo: homosexuality. “Until recently, there was almost nothing less acceptable in Cuban society than homosexuality.” A little late for those who spent years in that hospital on the airport road, and a sad holdover of Che Guevara’s New Man, but New Man was a bit of an automaton anyway, a perfect example of “subtropical delirium.” It is true that “the state accepts criticism”; it even admits its blame for many things, including “the state of Havana. The capital was never its priority.” (Nor did the US government’s waywardly malicious embargo help by hurting all the wrong people, a classic variation on our Drug War.) Then again, “the strength of the Cuban police state is that it is difficult to know what will lead to trouble.”

Throughout "Havana," the city’s history is called to speak. Here again, Kurlansky displays his talents as a chronicler well up to the challenge of a true, panoramic story, spinning with humanity and its evil twin, with predicaments, circumstances, forces and counterforces, incidents, availabilities, accidents, signs and wonders, down-and-outs. He starts with the Tainos’ eradication and the early years of Spanish Havana, a backwater founded by Diego Velázquez’s lieutenant, Pánfilo de Narváez, a man both “exceptionally brutal, even for that crowd, but also unusually stupid.” Still, smart enough to stay away from the mosquito-infested, disease-plagued swamps of Santiago and the earlier South Coast towns. To boot, newly founded Havana had the amusement of “so many tortoises and crabs crawling through the young town that after dark a tremendous racket of clawing and shuffling was heard.” One account told of a nighttime raiding party that, thinking the noise was a considerable army, retreated to their ship.

Cuba was a slave market as well as a slave country, though it also had free blacks as well, which in turn resulted in both considerable mixing of races and considerable racism. And slavery would stay with Cuba long after the other islands had foresworn it, a result of the political power of the sugar latifundia. Sugar, leather, tobacco, and shipyards, all slave-driven. Slavery shaped and defined the identity of Havana, socially and culturally. This is not to belittle the profound influence of Havana being a port, with all the amenities necessary to sailors: booze, gambling, and prostitution.

The United States would make its burgeoning imperial presence felt at the turn of the 20th century, occupying the country until its needs became too onerous to continue financing – a fixer-upper that required seemingly endless renewed investment – when control-at-a-distance became the preferred arrangement. The Platt Amendment, which turned Cuba into a vassal state, was finally defeated by the Cuban legislature, but a series of false starts and fiascos landed Cuba with a military dictatorship under Fulgencio Batista – murder was his go-to solution to nearly every problem – who found a cozy bed with American organized crime. Cuba’s party scene became an infamous stage for tourism at its most exploitative and indulgent, a wretched and poisonous case of bloat.

The 26th of July Movement was as inevitable as an American holiday maker’s sunburn. With the revolution that swept Fidel & Co. into Cuba on January 1, 1959, Kurlansky goes full reporter, trying to winnow fact from fiction and myth. Yes, there was rampant cronyism, and there were incredible strides in education and healthcare; yes, living under the thumb of conspicuous consumptionists became a thing of the past, and yes, there were Che’s tribunals, which “executed so many people by firing squad that Castro removed him from the post and made him the country’s bank president.” That was hitting below the belt. Che would move on to the Congo, then Bolivia.

Kurlansky’s Cuba is a well-stirred cauldron of turmoil, which he spices up with recipes for Cuban delectables: guajiras in song and ajiaco in the kitchen, and, from behind the bar the daiquiri – perfected in Havana, “in part by adding maraschino liqueur” (that being subject to debate), the mojito, and the Cuba Libre. That last required Coca-Cola, and thus local replication of the soda. ‘Twas done, as Cubans made do, ingenuity their stock-in-trade.

Certainly, Havana is “a city of unfinished works, of the feeble, the asymmetrical, and the abandoned,” as wrote its native son Alejo Carpentier. Kurlansky: “Havana, to be truthful, is a mess,” as so often is the one we love. But consider: who wouldn’t love a mechanic who kept your 1949 Ford coupe on the street by replacing the burned-out motor with a boat engine? He’s in Havana.