3 books about planets

Loading...

When Edgar Rice Burroughs in 1911 first began chronicling the adventures of Confederate captain John Carter on the far-flung world of Mars, it was still just possible for people – especially untrained enthusiasts like Burroughs himself – to believe that every planet in the solar system was teeming with life – just like Earth. Not only does Carter encounter dozens of advanced civilizations on the world its inhabitants call Barsoom, but he faces interplanetary invaders from Jupiter. For good measure, Burroughs later recounted for readers the exploits of Carson Napier on an equally-teeming planet Venus.

Twentieth-century astronomy gradually, inexorably, sucked the life-blood out of such fantastic tales. Telescopes constantly improved, planetary probes were launched with increasing frequency, and eventually it became clear that the solar system harbors no complex life – certainly no civilizations – anywhere except on Earth. The Mars where John Carter had so many thrilling adventures turned out to be a frozen, lifeless place that hasn't held surface water or ample atmosphere in billions of years. The Venus that was Carson's second home is a hellscape of crushing, superheated atmospheric pressure. Hardy microbes may live deep underground in such places, but there were no monsters, no maidens in need of saving, no masterminds devising evil plans.

It was a disappointment for the ever-fertile human imagination, but what scientific inquiry takes away with one hand it often gives back with the other: The more astronomy has learned about our solar system, the more fascinating these lifeless worlds have become.

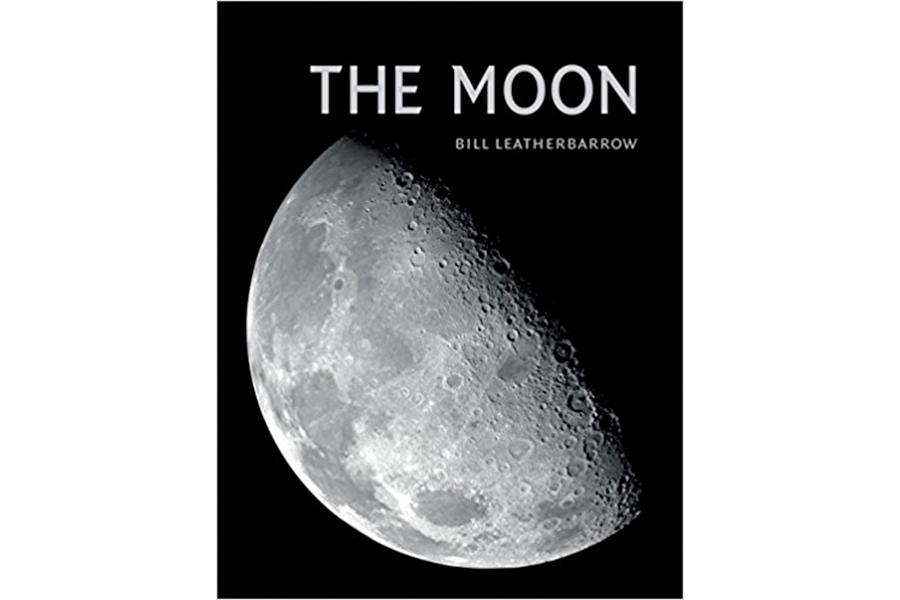

This is certainly true of Earth's nearest neighbor and very nearly sister planet, the moon. It's in every way the most familiar of all our celestial neighbors, and yet, as Bill Leatherbarrow's beautifully illustrated new book makes clear, the moon still holds surprises. Wonderfully produced by Reaktion Books, The Moon takes readers through the various stages of humanity's curiosity about the moon, including the first rudimentary attempts to understand what this luminous object in the sky actually was. Leatherbarrow's energetic narrative tells the familiar story of the leaps science has made in seeing this next-door neighbor clearly.

The moon remains the only other world in the solar system that humans have visited in person, but for over 30 years, there's been a persistent dream – both inside and outside the halls of NASA – to add an obvious candidate to that list. Venus would crush and broil any human visitors, but Mars? Mars is forbiddingly cold, but otherwise it's almost refreshingly Earthlike. Its thin atmosphere makes its sere rock landscapes look like something a well-provisioned hiker might find in the Mojave Desert, and at the right latitudes, there appears to be ample ice for provisioning.

These and other factors are the fuel for the optimism of David Weintraub's new book, Life on Mars: What to Know Before We Go, which opens with the age-old question: “Does life exist on Mars? … Could primitive microoganisms survive on Mars, living in subsurface reservoirs of liquid water? Yes. Long ago, could spores have been transferred via a large impact event from Mars to Earth or from Earth to Mars? Very possibly.”

Even so, the “life” on Mars he envisions in these terrific pages isn't romantic civilizations of green warriors: It's humans, moving first to set foot on the red planet and then to explore it and then to colonize it. Weintraub tackles every aspect of how humans could set up shop, all of it based on the successive space probes that have been launched over the decades. Weintraub tells the stories of this amazing exploration-tale with the authority of an astronomy professor and the verve of a true believer.

Colonization will never be the dream of Chasing New Horizons, the new book by Alan Stern and David Grinspoon. Pluto, now downgraded to the status of a dwarf planet, is billions of miles away from Earth, a fraction of Earth's mass, receives a sliver of Earth's sunlight, and is almost inconceivably cold. The chances that humans will ever establish a base there are correspondingly minuscule.

Instead, much like Leatherbarrow and Weintraub, Stern and Grinspoon concentrate on the heroism of learning, specifically the dogged, day-to-day heroism of the men and women behind the New Horizons spacecraft that in July of 2015 made the first-ever close fly-by of tiny frozen Pluto and sent back large amounts of invaluable data to the specialists who had nervously watched the crafts progress for years.

“The people who created this amazing mission of exploration chased their new horizons hard; they never let go of their dreams; they put everything they had into it; and eventually they chased it down and accomplished what they set out to do,” our authors write, allowing themselves a moment of the kind of jubilation that runs through all these books. “We did it. We really did. We were there.”