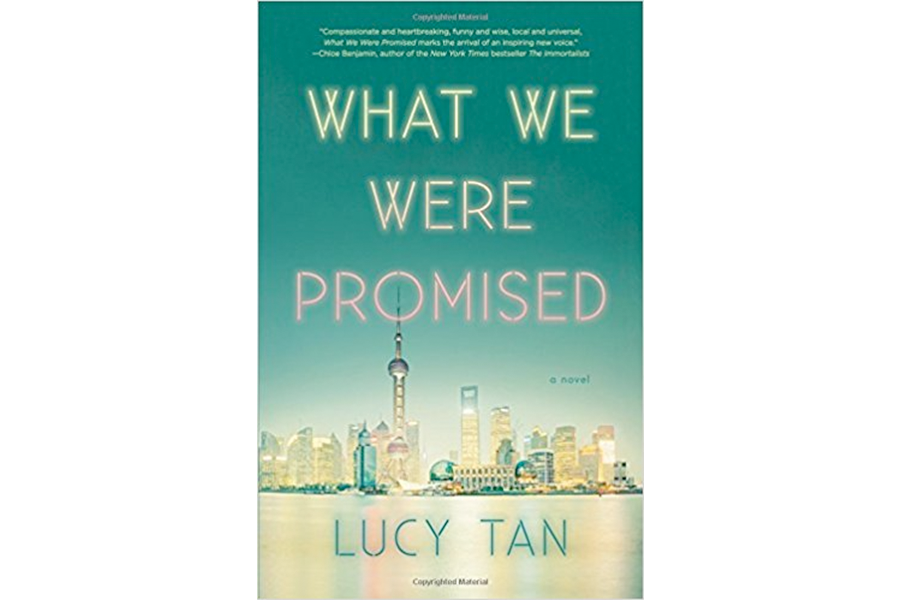

'What We Were Promised' depicts post-Mao China in a deft debut novel set in Shanghai

Loading...

Beyond divisions of class, culture, and background, a single African ivory bracelet connects a Chinese American ex-pat family, their staff who enable their (over)privileged lives, and their left-behind Chinese families in Lucy Tan’s intriguing, Shanghai-set debut novel, What We Were Promised. When the emblematic bracelet goes missing, two maids, Sunny and Rose, fall under suspicion as they were the last to access the Zhen home, a luxurious apartment in a fully-serviced residence hotel in Shanghai. After earning a graduate degree from the University of Pennsylvania, establishing his career, having and raising an American-born daughter, Wei Zhen’s promotion by his New York-based advertising company to “GENERAL MANAGER, SHANGHAI; VICE PRESIDENT OF STRATEGY, GLOBAL” has turned his small family into reverse immigrants.

While Wei spends exponentially more time at his office than at home, his former schoolteacher wife Lina has settled into being a taitai – “ladies of luxury who could not be called housewives because … they did no housework at all.” Besides spending excessively, her days are spent picking at meals and gossiping with fellow ex-pat spouses she can’t even call friends. She looks “[t]hirty-five rather than forty-three,” but being “unemployed with benefits” has left Lina feeling “useless” and “aware of her loneliness,” magnified by waiting nine months every year for 12-year-old Karen to return from her “American privilege” of being a Stateside boarding school commuter.

Summer break brings Karen back to Shanghai, making the Zhen apartment a little less empty. Lina adds Sunny to the household – despite the looming accusation of theft – elevating her from hotel maid to Karen’s ayi, a glorified nanny. And then another Zhen arrives: Wei’s younger brother Qiang, who after more than two decades of missing silence, announces he’s Shanghai-bound, ostensibly to attend the World Expo, and bringing with him memories of shared past.

Wei, Qiang, and Lina grew up together in a remote silk-producing village. Wei and Lina were promised to each other as children by their respective fathers, but Lina and Qiang chose each other as teenagers. Yet Wei and Lina’s wedding still happened, and Qiang disappeared shortly thereafter. Wei intermittently assumed his estranged brother was dead, given his involvement with hei shegui, “‘black society’” – gang life. Now Qiang’s imminent visit is about to unbalance the Zhen household: Wei thinks Qiang’s return is all about business, Lina is convinced it’s personal, but Qiang has a surprising, too-long-kept-secret agenda of his own.

Which brings readers back to that all-encompassing ivory bracelet, a mere object that surpasses borders, generations, relationships, social mores – proving to be an unexpected equalizer of sorts. Originally acquired by a peripatetic Chinese importer, Qiang wins the bangle during a gambling session and presents it to Lina just before she leaves for university. Lina never divulges its provenance, avoiding the truth by lying to Karen and telling her that it was a gift from her mother. Wei will never know its story. Sunny and Rose both recognize who took it, but neither will ever confess. One of these searching souls will be left holding the nebulous prize by book’s end.

Tan, a former actress and product manager raised in New Jersey who has spent the last decade commuting between New York and Shanghai, shrinks the 21st-century global stage into the microcosm of Lanson Suites #8202. Through the intertwined lives of the extended Zhen family and staff, Tan deftly explores evolving immigrant identity, layers of ex-pat privilege, tenacious gender disparity, family expectations and obligations.

Moving back and forth between 2010 Shanghai and previous decades spent in suburban Philadelphia and rural China, Tan outlines the unfathomable changes between the generations that survived Mao, and the newest internationally-savvy movers-and-shakers. She examines the not-so-subtle maneuverings of the seemingly powerful and not-so-powerless as she unblinkingly confronts the strained relationship between employer and employee, further exacerbated when both parties are Chinese-born and separated only by access to education and seemingly random opportunities. Smoothly bypassing melodrama, Tan especially excels in revealing Sunny’s life away from the luxurious entitlement to which she is both witness, and albeit unequal, occasional participant.

Tan boosts China’s clear emergence as a global leader with the looming presence of the World Expo – proof that the world now comes to China with both money and manpower. That the Zhen family is scheduled to move from the already lofty 20th floor to the coveted penthouse speaks volumes as to their literal upward mobility. Against a contemporary global backdrop, made empathic with a multigenerational family saga, embellished with timeless servant/master (and mistress) class conflict, Tan’s debut will be entertaining – and enlightening – savvy cosmopolitan readers throughout the summer and beyond.

Terry Hong writes BookDragon, a book blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.