Yet more literary furor over fake book reviews

Loading...

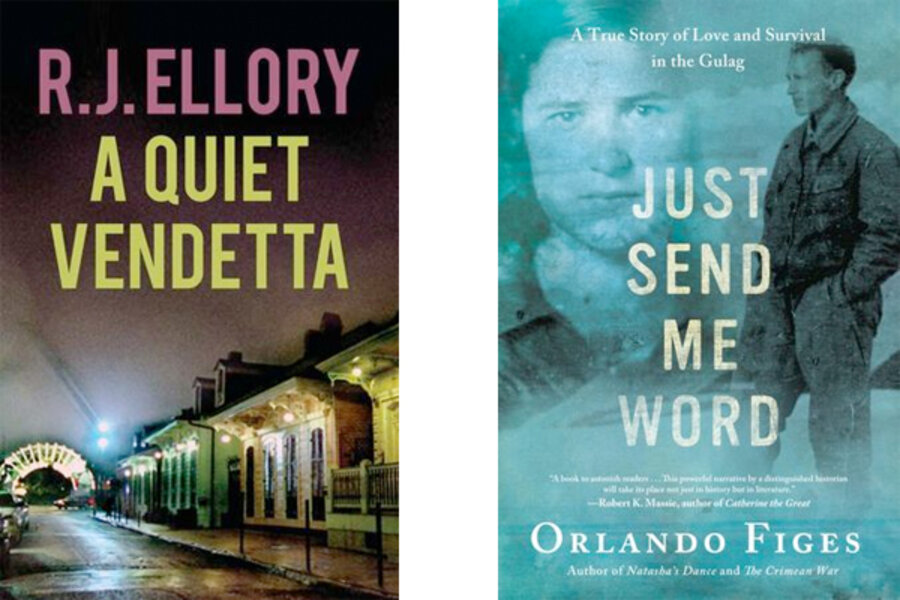

You may not have heard of him, but British crime writer R.J. Ellory’s “ability to craft the English language is breathtaking.” One of his crime novels has been called “a modern masterpiece” that “will touch your soul.” He is, in fact, “one of the most talented authors of today.”

That is, at least, according to R.J. Ellory.

Over the Labor Day weekend, the bestselling British author was caught praising his own books on Amazon using a number of pseudonyms while slamming the books of his competitors. Ellory used at least two pseudonyms, including "Nicodemus Jones" and "Jelly Bean," to heap praise on his works, including “A Quiet Belief in Angels,” an award-winning 2008 book which the author himself called “a modern masterpiece,” and “chilling,” saying, “Whatever else it might do, it will touch your soul,” according to industry newsletter Shelf Awareness.

Astonishingly, this practice went on for the past 10 years before fellow British thriller writer Jeremy Duns pieced together a case against Ellory and shared his suspicions via Twitter. Confronted, Ellory admitted to using pseudonymous handles to write his own glowing reviews on Amazon, a practice known as "sock puppeting."

“The recent reviews – both positive and negative – that have been posted on my Amazon accounts are my responsibility and my responsibility alone,” Ellory said in a statement. “I wholeheartedly regret the lapse of judgment that allowed personal opinions to be disseminated in this way and I would like to apologise to my readers and the writing community.”

Since then, writes the LA Times, “a furor has erupted in England over sock puppet Amazon reviews” and quickly spread to American shores. A group of 49 British authors wrote an open letter to the Daily Telegraph condemning sock puppeting.

“These days more and more books are bought, sold, and recommended online, and the health of this exciting new ecosystem depends entirely on free and honest conversation among readers,” the authors, who included Ian Rankin, Lee Child, Val McDermid, Susan Hill and Helen FitzGerald, wrote. “But some writers are misusing these new channels in ways that are fraudulent and damaging to publishing at large.... We unreservedly condemn this behaviour, and commit never to use such tactics.” They added, “The only lasting solution is for readers to take possession of the process.... Your honest and heartfelt reviews, good or bad, enthusiastic or disapproving, can drown out the phoney voices, and the underhanded tactics will be marginalised to the point of irrelevance.”

Ellory is just the latest subject in a string of review scandals to hit the literary world. Two years ago, historian and writer Orlando Figes was similarly accused of vaunting his own books and skewering rivals’ works on Amazon. More recently, another bestselling thriller writer, Stephen Leather, has admitted to using pseudonyms online, even holding online conversations with himself, to build excitement about his novels. And hardly a week has passed since The New York Times ran “The Best Book Reviews Money Can Buy,” which told the tale of literary entrepreneur Todd Rutherford, who raked in hundreds of thousands of dollars selling fake reviews through his business, GettingBookReviews.com, which we blogged on last week.

Cast the net a little wider and we find Jonah Lehrer and Fareed Zakaria, two more literary stars accused of making up quotes and plagiarizing, respectively.

The incessant spate of literary lying has us wondering, is 2012 the year of deceit?

One thing’s for sure, the anonymity of the Internet and social media, combined with the publishing industry’s ravenous pursuit for buzz, has helped to create this monster of a problem, an iceberg of deception of which we suspect, we’ve only seen the tip. (How many more fake reviews are out there? University of Illinois, Chicago data mining expert Bing Liu estimates one-third of online reviews are fake, according to this NYT piece.)

And yet, it turns out, literary lying, sock-puppeting, and blatant self-promotion are nothing new. Lest you think our ethics have warped and waned with the times, consider this: Walt Whitman was “one of history’s most unrepentant self-promoters," according to the Atlantic. “He anonymously submitted glowing reviews of his own poetry collection ‘Leaves of Grass’ to newspapers across New York,” writes the Atlantic’s David Wagner, including this gem:

“An American bard at last! One of the roughs, large, proud, affectionate, eating, drinking, and breeding, his costume manly and free, his face sunburnt and bearded, his posture strong and erect, his voice bringing hope and prophecy to the generous races of young and old. We shall cease shamming and be what we really are. We shall start an athletic and defiant literature. We realize now how it is, and what was most lacking. The interior American republic shall also be declared free and independent."

And, well, look where it got him.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.