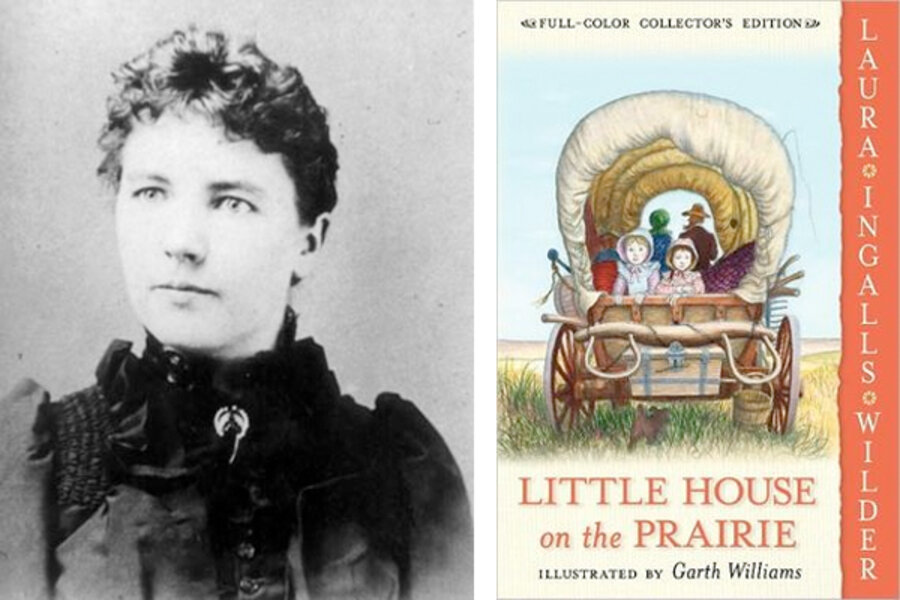

Laura Ingalls Wilder chronicles pioneer life for multiple generations

Loading...

“A long time ago, when all the grandfathers and grandmothers of today were little boys and little girls or very small babies, or perhaps not even born, Pa and Ma and Mary and Laura and Baby Carrie left their little house in the Big Woods of Wisconsin.”

So begins Laura Ingalls Wilder’s book “Little House on the Prairie,” the second in her series about pioneer living and arguably the most famous of the collection.

By this point, 146 years after Wilder was born, the grandfathers and grandmothers she was envisioning are probably the great- or great-great forebears of those living today. But schoolchildren are still picking up Wilder’s stories about surviving on the frontier, reading her stories about taking part in activities from preserving meat to going to a community dance and even to battling malaria.

“You feel such a strong identification with Laura,” writer and Wilder expert Wendy McClure told The Atlantic. “There's something about the narrative. You feel like you're right there with her, or even that you're seeing it through her eyes…. I love the idea that the history of the American West is kind of paralleled with the lifespan of an American girl.”

Wilder was born in Wisconsin, on Feb. 7, 1867, to Charles and Caroline Ingalls, who are today familiar to readers worldwide as "Ma" and "Pa." (The names of Laura, her parents and siblings were all kept intact for the “Little House” novels.) Ingalls lived in Wisconsin until her father moved the family to Kansas, where he had heard there was land available for homesteading. Later, Charles Ingalls traveled to the Dakota Territory, where he worked on the railroad, and was eventually joined by the rest of the family members.

The years in Wisconsin were the basis for Wilder’s first book, “Little House in the Big Woods,” while the Kansas sojourn makes up the story of “Little House on the Prairie.” The harsh season the family endured in the Dakota territory was the basis of the plotline of “The Long Winter,” and the rest of their time in the Dakotas was chronicled by Wilder in “Little Town on the Prairie” and “These Happy Golden Years.”

It was in the town of De Smet in modern-day South Dakota that Wilder met her future husband, Almanzo Wilder, who later earned his own book, titled “Farmer Boy,” about his childhood. Wilder began teaching at age 16 and also attended high school, leaving both when she married Almanzo Wilder at age 18. Almanzo had staked a claim on land north of De Smet, and they settled there, where Wilder gave birth to their daughter Rose and a son who died soon after his birth.

After their marriage, Almanzo was struck with diphtheria that left him carrying a cane for the rest of his life. The couple and Rose moved to various homes, including one in Florida and another in Missouri, finally settling in Mansfield, Mo.

Besides her famous series, Wilder worked as an editor and columnist for the newspaper the Missouri Ruralist.

The literary community is still uncertain today how much of a role Wilder’s daughter Rose, a writer herself, had in the Little House manuscripts. “Little House in the Big Woods” was first released in 1932, with “Little House on the Prairie” following in 1935 and the subsequent books published every few years thereafter. “Golden Years” was released in 1943, after which Wilder went back and wrote the story of Almanzo’s childhood, “Farmer Boy,” which was released in 1955.

Titles that were published after Wilder’s death include “The First Four Years,” which chronicles the early years of the Wilders’ marriage; “On the Way Home,” which tells the story of the Wilders’ move from South Dakota to Missouri; and “West from Home,” made up of letters Wilder wrote to Almanzo while she was in California visiting Rose.

A new generation of children was introduced to the author's stories when the TV series “Little House on the Prairie” aired on NBC from 1974 to 1982, with actor Michael Landon starring as Charles Ingalls.

Today there are three separate museums devoted to the author, one created from the family’s home in Mansfield, Mo.; one in Walnut Grove, Minn.; and the third in De Smet, S.D.