What's the best way to bring young people back to reading?

Loading...

In the summers of her early childhood, my daughter would often haul a couple of chairs into the yard, cover them with a blanket to form a makeshift tent, then furnish the interior with favorite volumes from her bedroom bookshelf.

I’d be invited to bring a flashlight into this home away from home, the two of us hiding from the world as we took turns reading aloud from “Eloise,” “Amelia Bedelia,” or “Geronimo Stilton.”

But that was years ago, and my daughter, who turns 18 this month and is heading off to college, doesn’t read nearly as much as she used to. She apparently has plenty of company. Common Sense Media, a nonprofit that tracks media and technology usage in children, released a report this month indicating that about a third of 13-year-olds and nearly half of 17-year-olds read for fun less than twice a year.

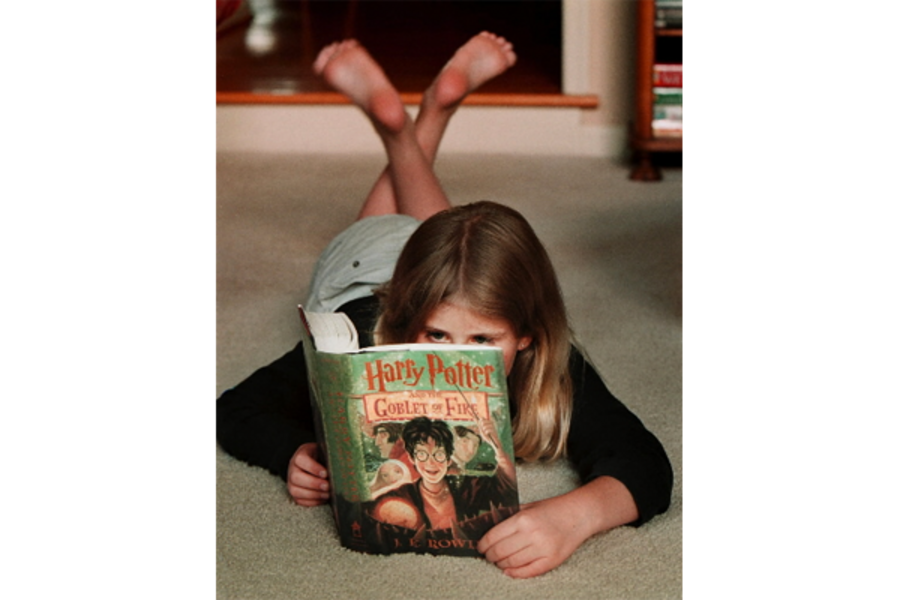

The report, which echoes similar findings from other recent studies on the subject, didn’t surprise me. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed last year, I told readers about my own informal survey of reading habits, when I asked college students in my writing class to name the last book they’d read for pleasure. More than half of the students listed a Harry Potter novel – a strong clue that they hadn’t read for pleasure since middle school.

What’s clear to me, as both a father and a sometime adjunct instructor, is that we’re not going to have much luck scolding young people into reading more. Pleasure is, by its nature, an indulgence of personal choice, not an assignment carried out to answer the call of duty.

But in these warm days at the threshold of another summer, I’ve been quietly haunted by the memory of that reading tent in our front yard. What did it promise, and how might that promise be reclaimed? What my daughter was seeking in her books back then, I suppose, was what she wanted in that homemade room of blanket and chairs: a sense of complete enclosure, a separate realm, a remove from the dailiness of private life.

That’s probably why the Harry Potter books were such a sensation for members of my daughter’s generation. They offered a self-contained universe, as smartly encapsulated as the village of a snow globe, an intricate dominion that could, miraculously enough, be held in the palm of one’s hand.

What I’m trying to describe, I guess, is the chance to not only scan a narrative but inhabit it, living within the walls of a text. That’s why Internet culture is so appealing to young people; it’s immersive, not so much a pastime as a way of life. If we want to lure young people back to books, we’ll have to persuade them that sustained reading also offers this kind of absorption, a way to slip beneath the surface of the everyday and discover an alternate reality.

Lying beneath a blanket and sharing a book, my daughter and I found emotional and spiritual intimacy, too. That hunger for connection with another soul never really leaves us, and it’s especially sharp in the years when we begin to break away from our parents and chart our own path. I’d like young people to know that even as they grow into adults, reading for pleasure still offers the same kind of bonding we once found in storytime as children.

I learned as much in high school when a friend pressed a copy of John Kennedy Toole’s comic novel “A Confederacy of Dunces” into my hand and insisted that I read it. I acquiesced – discovering, as he had, that the book had somehow altered my DNA. We emerged from the book as two changed people who’d shared the same journey, and there’s nothing quite like that kind of mutual literary experience.

I haven’t found a way to talk about these things with my daughter without lecturing her. When she moves into her dormitory this year, I’ll give her a new reading lamp and a book or two, hoping she discovers – or rediscovers – the wonder of reading on her own.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”