Before Rachel Dolezal, what did it mean to ‘pass’?

Loading...

Allyson Hobbs, a history professor at Stanford University, remembers hearing a story from her aunt about a distant cousin who who grew up on the South Side of Chicago during the 1920s and 1930s.

The cousin was African-American, like Hobbs. But she was light-skinned, “and when she was in high school, her mother wanted her to go to Los Angeles and pass as a white woman,” Hobbs recalls. “Her mother thought this would be the best thing she could do.”

The cousin didn’t want to go but followed her mother’s wishes. She married a white man and had children. About a decade later, Hobbs says, the cousin’s mother contacted her: “You have to come home immediately, your father is dying.”

But it was not to be. “I can’t come home. I’m a white woman now,” the cousin replied. “There’s no turning back. This is the life that you made for me, and the life I have to live now.”

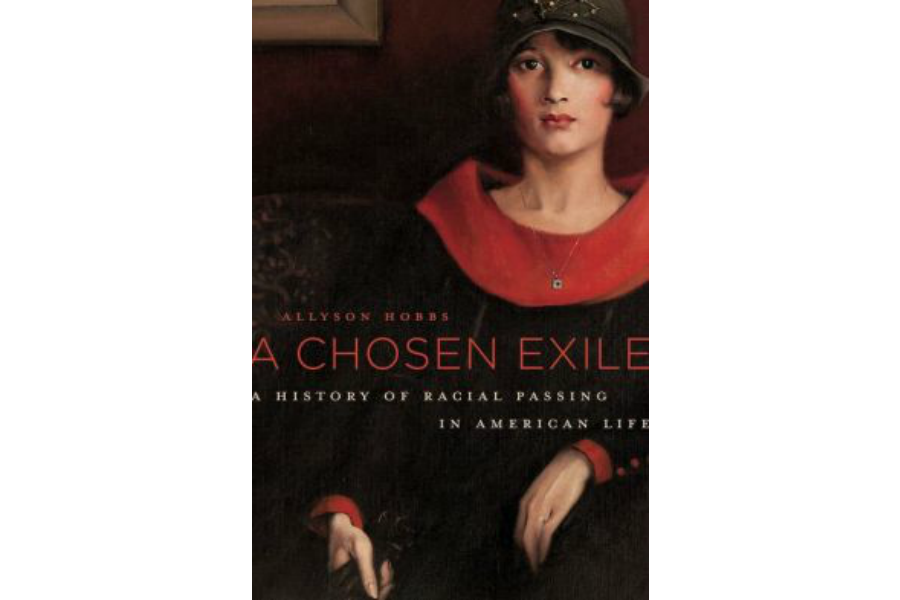

This remarkable tale inspired Hobbs to investigate the long history of blacks passing as whites in her well-received 2014 book A Chosen Exile: A History of Racial Passing in American Life.

The topic of racial passing has filled the airwaves this month amid the controversy over a once-obscure local civil-rights official named Rachel Dolezal. Hobbs adds to the debate this week with New York Times commentary that offers an unexpectedly sympathetic take amid vitriol aimed at Dolezal.

“The harsh criticism of her sounds frighteningly similar to the way African-Americans were treated when it was discovered that they had passed as white....” Hobbs writes. “Of course there are huge differences between passing as white and passing as black. But both practices have psychological costs and entail a painful rupture with family.”

In an interview, Hobbs talks about the role of race in the Dolezal controversy, the lessons learned from those who passed, and the personal world she sees in the stunning portrait on the cover of her book.

Q: What do you think about Rachel Dolezal?

It’s worthwhile to give some thought to her overall life circumstances. When you do that, you gain more sympathy and understanding of passing and how painful and difficult it can be.

People say she can always go back to being white at any time and take it off almost as if it was a cloak. I don’t know if she can do this. It seems like this is really who she is. I’m not convinced that she would go back to being white or could go back to being white. And I do understand why that becomes such a source of tension.

Q: When I grew up, a relative warned me (a white guy) to never marry a black woman because our kids wouldn’t know what they are. That was an odd opinion then, and it’s odd now. But it reveals how race is often seen as either-or: You’re this or you’re that, and in-between violates some sort of social law. Your book looks at people who transitioned – “passed” – between the races. Did you look at anyone who wasn’t actually sure where they fit in before they made the switch?

Part of my book’s reason for being is to say that race is not real; it’s a social construction. I didn’t want to make judgments about whether someone is white or black. So I only look at people who identified as black and made a very deliberate choice to pass as white.

That's what makes the Rachel Dolezal case so interesting. She feels very certain that she is black. She’s challenging the kind of frameworks we have for thinking about passing.

Q: What motives did black people have for passing?

For the people who could pass, this could be a method of survival, a way to get ahead.

If this is what it takes to survive and live a much better life, why shouldn’t I do this? In some cases, they’d only pass as white at work, from 9-5, and think, “then I’ll have my life as a black person.”

There’s a famous passage in a novel called “The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man.” The main character plans to return to the black race, and then he stumbles upon a lynching. At that moment, he thinks, “I can’t be black. I can’t identify myself with a race that can be treated worse than animals.”

If you could pass, why not get away from all of that?

Q: What happens when people discover that someone is passing as white?

I did not find many cases where someone was discovered, and there are horrible consequences, although there were cases where they were discovered and lost their jobs or their marriage.

But there is a reaction that’s similar in tone to the way people talk about Rachel Dolezal: This is deception, this person does not deserve to be white, they’re stealing something that doesn’t belong to them. There’s a lot of that kind of language.

Q: Were black people more accepting than whites of those who were trying to pass as white?

Most blacks were pretty sympathetic, although there were definitely some who were not. Particularly during the years of Jim Crow, people recognized how difficult life was for blacks and recognized this was a way of getting ahead.

There was some humor or levity to it, a kind of practical joke at the expense of whites. It was very delicious for some blacks.

But there were some blacks who definitely disagreed with the practice of passing. They felt it was important for blacks to stay within the race and fight for the race.

Q: What can we learn from the people you profile in your book?

Race is a social construction. It’s not based in biology.

Skin color was perceived to be one of the most reliable ways to determine someone’s race, but if we look at the history of passing, that standard fails every time. If someone could look white and be taken as white for over 20 years, then skin color isn’t a factor that people can really count on.

I also hope to show what can be lost by passing. You had to walk away from your family, leave your community behind, and recreate an entirely new life in a new place. You had to be anonymous and couldn’t be any place where you could be revealed because someone knew your mother or grandmother.

Families could be ruptured and the pain of that comes up quite often in the sources: I decided to pass, and I ended up almost losing myself.

Q: Do black people still pass as white today?

Times really changed in the 1950s and 1960s, largely because the of the Civil Rights Movement. You have this period where there is an increased level of militancy, a sense of race pride and wanting to be visible as blacks.

There’s also a sense that barriers to segregation are falling. There’s this sense of opportunity. And we have increased numbers of mixed marriages and mixed children. It’s not like it used to be where you had to pick one, you’re black or you’re white, even on the Census.

Q: The painting on the cover of your book is a stunning 1925 portrait of an unknown woman by black artist Archibald Motley of the Harlem Renaissance period. The painting is called “The Octoroon Girl,” reflecting the apparent mix of races in the subject. (An octoroon is one-eighth black.) What does this painting say to you?

When you look at it, it evokes a lot of emotion. I just love the look of longing she seems to have that captures the argument I try to make about loss: Once you’ve accepted the life you have and it’s one you want, you still feel the loss. You’ve given something up.

Randy Dotinga, a Monitor contributor, is president of the American Society of Journalists and Authors.