My dad and his books

Loading...

As another Father’s Day arrives, I’ve been thinking of a book on my shelf – and what it tells me about my own father, his connection to reading, and perhaps, in a broader way, the role that fathers can play in nurturing our love of the printed word.

It’s “New Zealand,” by the New Zealand mystery novelist Ngaio Marsh. Maybe you’ve heard of Marsh, whose fictional Inspector Roderick Alleyn of London’s Metropolitan Police invited favorable comparisons with the stories of Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers.

But "New Zealand" isn’t one of Marsh’s crime novels. Published in 1942, it’s a slender popular survey of Marsh’s native country that was part of a series, “The British Commonwealth in Pictures,” that paired lively text and beautiful illustrations to chronicle various outposts of what was, or had been, the British Empire. My father picked up the book while serving in the South Pacific during World War II.

Just think of it: a sailor far from home, on a cramped, steaming, unairconditioned ship, facing daily threat of attack by the Japanese. It was in this place, at this time, in these circumstances, that my father still thought of reading as something worthwhile.

And apparently, he wasn’t alone. Some years ago, while delivering a lecture in Baltimore, I connected with Arthur Gutman, a retired insurance executive who had done much to keep alive the legacy of Baltimore’s celebrated gadfly and man of letters, H.L. Mencken. Gutman told me that he’d developed a deep affection for Mencken’s writing after picking up a copy of Mencken’s comic memoir, “Heathen Days,” while fighting the Germans in North Africa during World War II. During wartime, as Gutman explained, the biggest enemy wasn’t bullets or bombs, hunger, heat or cold. It was boredom. Soldiers, sailors and airmen often passed the time by reading. Books reminded them that they were human. Books reminded them, too, what they were fighting for.

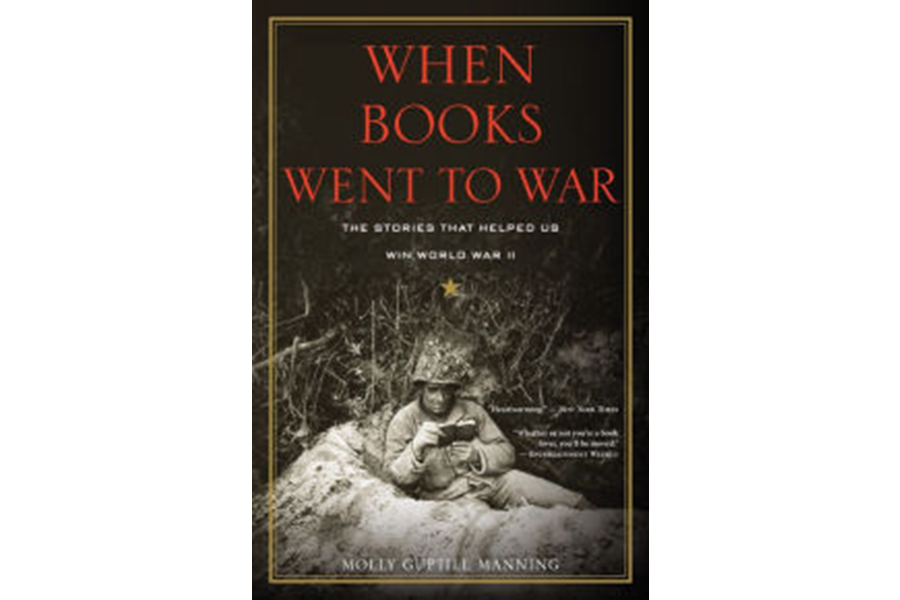

All of this has been beautifully explained in a lovely 2014 history, by Molly Guptill Manning, called “When Books Went to War: The Stories That Helped Us Win World War II.” It’s about the effort to provide American fighting men with reading material – first, through donated books, and then through special Armed Services Editions that offered portable paperback copies of authors ranging from Charles Dickens to Joseph Conrad, Edgar Allan Poe to William Mackpeace Thackeray, Herman Melville to Somerset Maugham.

My father made it back from the war safely, marrying and, along with my mother, raising six kids. The reading bug never left him, and he passed that passion to his daughters and sons, who have passed it along to their children, too. Whenever I hear someone suggest that reading somehow isn’t masculine – that real men don’t read – I think of his books on the shelf, the leavings of a man who risked his life in the South Pacific, then came home to work a construction job, reading all the while.

Daddy died in 1978. If we are lucky, then Father’s Day is a time to remember the men who taught us that books are something worthwhile. I will honor my own dad as I do every Father’s Day – by sitting for a few moments with a book in my lap, turning the page to see what happens next.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana and an essayist for Phi Kappa Phi Forum, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”