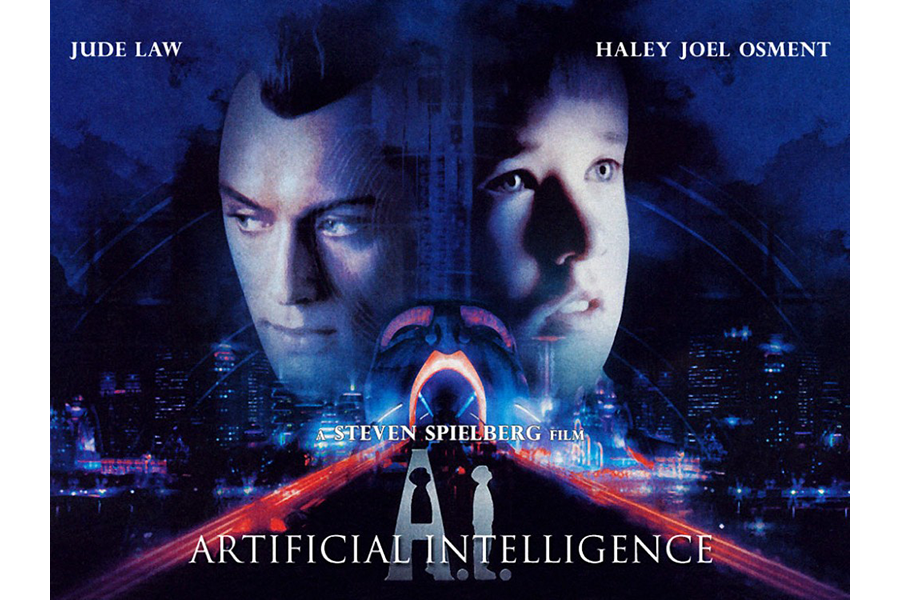

English science fiction great Brian Aldiss, author behind Spielberg film 'AI,' dies at 92

Loading...

One of the literary greats of science fiction, Brian Aldiss, a writer whose tales of alien empires, climate change, and the isolation of robots, helped elevate a genre, has died at 92.

The author, editor, artist, poet, and memoirist leaves behind four children, seven grandchildren, as well as more than 80 books, 40 anthologies, and numerous essays, short stories, and poems.

Mr. Aldiss is perhaps best known for science fiction classics including the 1958 space travel novel, “Non-Stop;” the dystopian “Hothouse,” in which half the Earth is covered by a towering banyan tree; the 1964 “Greybeard,” about a world without young people; the 1980s “Helliconia” trilogy, about a planet with centuries-long seasons and ice ages; and the 1969 short story “Super-Toys Last All Summer Long,” about the struggle a woman has connecting with her son, an artificially intelligent robot named David, a work that was eventually adapted into the Steven Spielberg film “AI Artificial Intelligence.”

Aldiss, who was inspired by H.G. Wells and corresponded with J.R.R. Tolkien and CS Lewis, was praised throughout the literary world.

English author Neil Gaiman described his career as “enormous.”

“It has recapitulated British SF, always with a ferocious intelligence, always with poetry and oddness, always with passion; while his work outside the boundaries of science fiction, as a writer of mainstream fiction, gained respect and attention from the wider world,” he wrote in an introduction to a new edition of “Hothouse.”

On Twitter, he described Aldiss as a “larger than life wise writer,” adding that the news “just hit me like a meteor to the heart.”

Scottish author Stuart Kelly described Aldiss as “the grand old man of British science fiction.”

And English science fiction novelist Adam Roberts called him “a giant of the genre.”

Among the many awards and recognitions Aldiss received were the Hugo and Nebula prizes for science fiction and fantasy.

The author was born in 1925 to a shopkeeper father who beat him and then made him shake hands to “prove that we were still friends.” As a 3-year-old, young Aldiss began to write stories that his mother would bind and put on the shelf. After a younger sister was born, he was sent away to boarding school where he was beaten for telling ghost stories after dark, which inspired the first Horatio Stubbs novel, “The Hand-Reared Boy.”

He joined the Royal Signals during World War II and saw action in Burma, an experience that inspired the Horatio Stubbs books “A Soldier Erect,” and “A Rude Awakening.”

Aldiss helped shape and elevate the science fiction genre, but he recognized its mutability.

As he told Publishers Weekly in 1985, “I don’t look upon science fiction as a genre at all; rather it contains genres. For a bit it was the open space opera that was in vogue. Then the catastrophe novel. For every kind of story that gets used up, another will always take its place.”