Robert E. Lee and George Washington do not equate, says Lee biographer Jonathan Horn

Loading...

In the heat of the debate over Confederate monuments, the names of two generals – Robert E. Lee and George Washington – were linked.

"Is it George Washington next week?" Donald Trump asked, amid the furor over the removal of a statue of Lee.

John Dowd, an outside attorney to President Trump, then circulated an email stating: "You cannot be against General Lee and be for General Washington, there literally is no difference between the two men.”

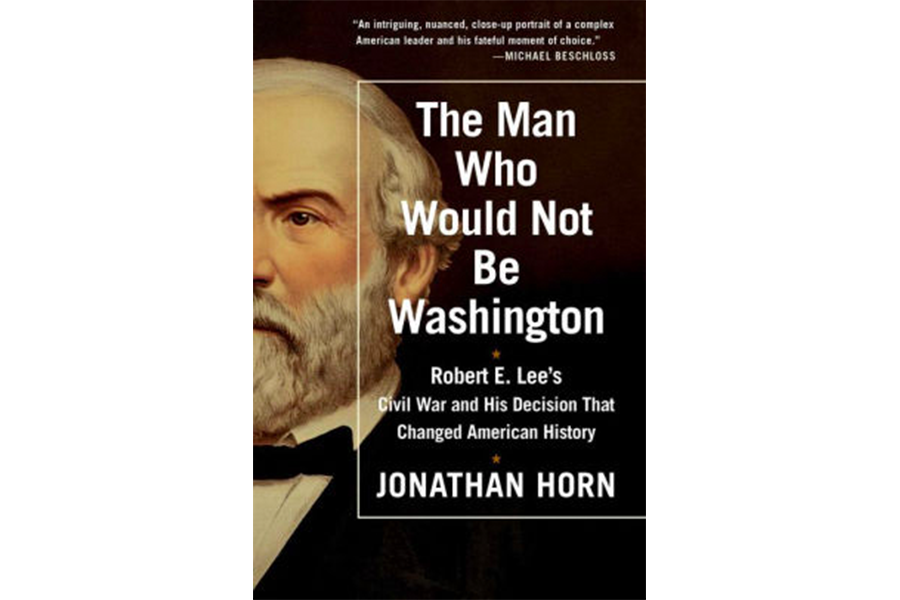

Historian Jonathan Horn, a former speechwriter for President George W. Bush, explains why the two men should not be equated in the title of his well-received 2015 book The Man Who Would Not Be Washington: Robert E. Lee's Civil War and His Decision that Changed American History.

In an interview with the Monitor, Horn talks about the surprisingly deep personal ties between the two generals, their conflicting views on loyalty, and the mistaken notion that history should unite them as one.

"There couldn't be anything more ridiculous than saying they were the exact same person," Horn says. "Lee makes a decision that puts him at war against George Washington's legacy."

Q: What do you think about Lee's role in history?

He's a uniquely tragic figure, a man who feels he has no choice when he faces this great decision. He's fond of saying he can never have things his own way.

Lee is the son of George Washington's eulogist, who'd said the president was "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen," and he'd married the daughter of George Washington's adopted son, Martha Washington's grandson from a previous marriage.

But he makes this decision that puts him at war against Washington's legacy as the man who created our union.

Q: How close did things come to going another way?

On the eve of the Civil War, Lee's letters are pretty clear. He thinks secession was illegal, he thinks George Washington would agree, and he opposes it.

In April 1861, Lee is called to the city of Washington by an emissary for Abraham Lincoln who tries to get Lee to crush secession. As Lee remembers the story, the emissary tries everything to get him to say yes and says, "the country looks to you as the representative of the Washington family."

Yet he makes this decision to turn down that command, and he says he can't go to war against the state he calls home, Virginia. He explains this decision to his mentor in the Union Army who says, Lee, you've made the greatest mistake in your life.

But Lee believes that he has to follow his native state, where his first loyalty is due.

Q: What did Lee think about slavery?

Lee famously says slavery is an evil institution, but in the very same letter, he writes that he thinks it is a necessary institution for the time being.

And he thinks slavery was worse for whites than for the slaves themselves. That sounds incomprehensible to us today, but he does not want to be dependent on slave labor.

Q: How did Washington look at these kinds of loyalties?

He had come to view to himself as an American first. The best evidence for this is his Farewell Address, which instructs Americans to put the union above any local allegiance.

Q: What would Lee have thought of all the monuments to him?

He is very reluctant to support building monuments. He gets letters asking for his support, but he doesn't think people can afford to build monuments, and at others times he says it might anger the victorious federals.

He probably doesn't even support preserving the battlefields because countries that hide reminders of sectional strife move on quicker. He is worried that preserving the reminders of the past might preserve the passions that had divided the country.

Q: How do his opinions change after the war?

Before the war, he says the founding fathers couldn't have possibly allowed for secession. After the civil war, he says the good men of the country had always agreed that this was a possibility.

He also explains that men can fight for causes that are contradictory. George Washington had fought with the British during the French and Indian War, and he fought against them during the Revolution. That's how Lee justified his own actions.

He ultimately cast his fate on the wrong side of history, and there really couldn't have been a worse cause.