Author Malachy Tallack dives into the world of 'un-discovered islands'

Loading...

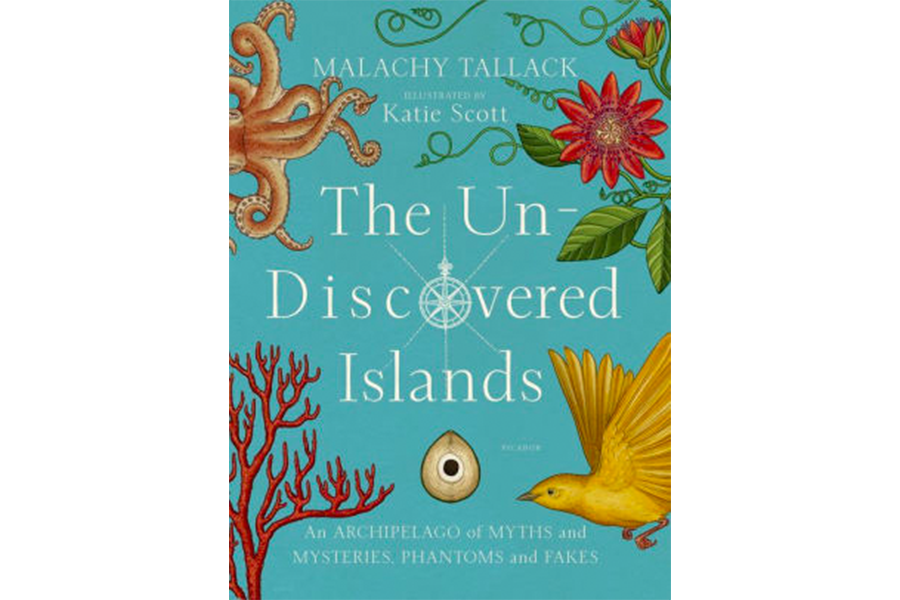

Malachy Tallack, a young Scottish author and singer-songwriter, takes readers through the world's Found-Then-Lost Department in his intriguing new book The Un-Discovered Islands: An Archipelago of Myths and Mysteries, Phantoms and Fakes.

As Tallack put it in an interview with the Monitor, "an 'un-discovered' island is one that was believed to be real, for whatever reason, but which turned out not to be."

Some are products of myth and legend like the famous Atlantis. Others have more unexpected origins like fraud. And a few actually were once considered real by scientists and geographers as recently as this decade. It turned out they weren't where they were supposed to be – or anywhere else.

Tallack talked to us about the hold islands have on our imaginations, his own mixed feelings about growing up on an island himself, and the sad but likely end of un-discoveries.

Q: What inspired you to write a book about un-discovered islands?

I read about two of these islands during the research for my previous book, "Sixty Degrees North: Around the World in Search of Home," and I was fascinated. It didn’t take long to realize that there were, in fact, many such places all over the world. Gathering some of them together in a book was a perfect project, more pleasure than work.

Q: What are the most sensible – and the least sensible – reasons for an island to be un-discovered?

The most common, and I suppose most sensible, reason for such places to exist – and also to not exist – was human error. Mariners made mistakes, and those mistakes would then be repeated by cartographers. Sometimes the error could go uncorrected for many years, even centuries.

The least sensible reason, perhaps, was deliberate fraud.

Q: It's hard to imagine writing a book like this about un-discovered continents, countries, cities. Islands seem to stand alone. In fact, the only other kind of "un-discovered" book I can think of would be about people who were thought to be real but weren't. Why do you think islands have this unique hold on the imagination?

Islands are, by definition, separate from other places. There is distance between them and the rest of that world. And that distance allows the imagination to go to work. People have always imposed their desires and their fears onto islands.

Q: How in the world – literally – are we still un-discovering islands in modern times? Were you surprised by that?

Digital maps were first built using information from paper maps, so it was possible for errors to make that leap to digital, and some certainly did.

Sandy Island, off Australia, was un-discovered in 2012. It appeared on Google Maps as well as many other charts but didn’t actually exist.

I think it’s highly unlikely that any more places of that size are still waiting to be un-discovered, but you never know.

Q: You grew up in the Shetland Islands, which will make just about every American think of ponies. How did growing up there affect you? Do you think you'd have turned out differently than if you'd grown up in elsewhere?

Growing up on an island turns some people into islomaniacs – that’s the official term for a lover of islands – and makes others desperate to leave.

I suppose I got a bit of both. I keep thinking and writing about islands, especially my own. But I also keep traveling.

Q. What are your favorite un-discovered islands?

I’m still fascinated by Thule, which was supposedly discovered more than two thousand years ago. It’s been associated with Shetland, with Norway, and with Iceland, and for a long time the name was synonymous with the far north.

I’m also really interested in mythical islands, such as the Isles of the Blessed, which were a kind of paradise on earth imagined by the ancient Greeks. People have been dreaming of islands for a very long time.

Q: If you could visit one of the un-discovered islands that you write about – re-discover it, maybe – which would it be?

Well, paradise on earth sounds like a pretty good place to visit, I suppose. Although the downside of the Isles of the Blessed, of course, is that nobody who went there could ever come back.

Q: Have you conjured (or un-discovered) islands in your own imagination?

I think all of us, without too much prompting, can imagine our perfect island. Mine would probably look much like home, in Shetland. But with better weather.

Q: What's on the horizon (so to speak) on the un-discovering front? Are we in for learning that more islands aren't really there?

The age of geographical discovery, on this planet at least, is pretty much over. And so too is the age of un-discovery. Satellite technology has made it easy to check and correct our previous mistakes.

Part of me wishes it wasn’t quite so easy, though. I rather wish we could keep a little mystery in the world.