Murdoch's bid to buy Sky TV: What that means for British media

Loading...

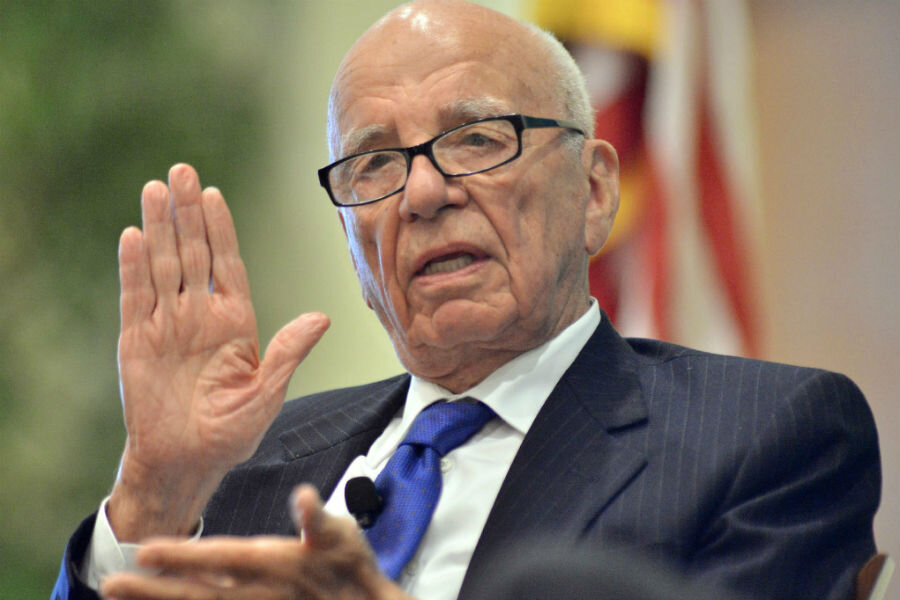

It’s a family affair: Five years after Rupert Murdoch’s failed bid to take over Sky, his son is trying again. Will the regulatory environment be more favorable this time around?

On Thursday, Fox TV announced that it had reached a $23 billion deal with the independent committee of Sky directors to take full control over the satellite pay TV service, which boasts almost 22 million subscribers across five countries. James Murdoch is the chief executive officer of Fox and chairman of Sky, in which Fox currently owns a 39 percent stake.

The deal has raised concerns that the Murdochs – who have long had a larger-than-life presence on the British political landscape – will become overly influential. The deal may face scrutiny from British communications watchdog Ofcom and European Union regulators – but some expect the government to be less concerned about this deal than Rupert Murdoch’s last attempt.

Mr. Murdoch has long been acknowledged as one of the British media’s most influential voices. Following the 1992 election, the Sun, a Murdoch tabloid, famously ran a headline, “It’s The Sun Wot Won It,” implying that the tabloid’s endorsement of the Conservative party had decided the outcome. Though Rupert Murdoch later rolled back that claim, saying “We don’t have that sort of power,” a group of scholars observed that around 2 percent of voters tend to change their party preferences as the newspaper switches sides, making a Murdoch endorsement an important political tool.

And in Britain’s unusually concentrated media landscape, where three companies – including the Murdochs’ – control more than 70 percent of national newspaper circulation, according to the Media Reform Coalition, some are concerned that allowing Fox to take over Sky would excessively limit media plurality. Sky is the biggest broadcaster in revenue terms, the MRC, which is based at Goldsmiths, University of London, reported in 2015.

But the merger isn’t a done deal – the government can still scrutinize it. When one media enterprise takes over another, there are usually grounds for a review under the Enterprise Act of 2002, writes Lorna Woods, a professor at the University of Essex School of Law, in an email to The Christian Science Monitor.

If Secretary of State for Culture Karen Bradley believes that Fox’s bid for Sky would threaten the public interest, she can issue a public interest intervention notice and trigger a review by communications watchdog Ofcom.

The idea is that a range of people should be in charge of the news sources for every audience, Professor Woods explains. There also needs to be a wide range of quality broadcasting, and media outlets should be committed to the standards required of broadcasters specifically, including impartial news.

Rupert Murdoch faced this kind of review when he attempted to merge his News Corp with Sky in 2011. The bid was ultimately withdrawn before a decision, in the face of the News of the World phone hacking scandal. But James Murdoch, now CEO of Fox, faced criticism for his management of that scandal, which Ofcom said “repeatedly fell short” of the standards expected, the BBC reported.

A failure to meet these standards – and, consequently, a decline in quality and impartiality – is certainly a concern for some Britons. The Guardian’s Polly Toynbee wrote, “Letting Fox own Sky will start the campaign to undermine the very notion of impartiality and accuracy.”

“Will @SkyNews then become #TrumpTVUK? Sad day,” tweeted American-British playwright and novelist Bonnie Greer, who is currently the chancellor of Kingston University.

The government may be less interested in a review than it was in 2011, when the hacking scandal prompted a public outcry.

“I would not expect a government with Brexit already on its plate to start pushing hard on this,” Stephane Beyazian, an analyst at financial services company Raymond James, told Bloomberg.

British Prime Minister Theresa May met with Rupert Murdoch after the Brexit vote. And Britain’s decision to leave the EU has certainly made the acquisition more feasible for Fox. The drop in the value of the pound means that, even paying a 40 percent premium to Sky shareholders, Sky only costs what it would have before the vote.

Woods warns that the deal – which is also subject to review by the EU – could still be politically problematic.

“Given how contentious the last attempt by a Murdoch Corporation was, this is likely to be a highly politicised debate,” she writes.

But history may offer a message of hope to both sides.

“Last time – prior to the phone hacking – the authorities had come up with solutions that they thought could operate to safeguard plurality,” Woods notes, though she qualifies that plurality "is not the only consideration" of these recommendations.