Is Wall Street falling back into bad habits?

Loading...

While attention is focused on Syria, the gambling addiction of Wall Street’s biggest banks is more dangerous than ever.

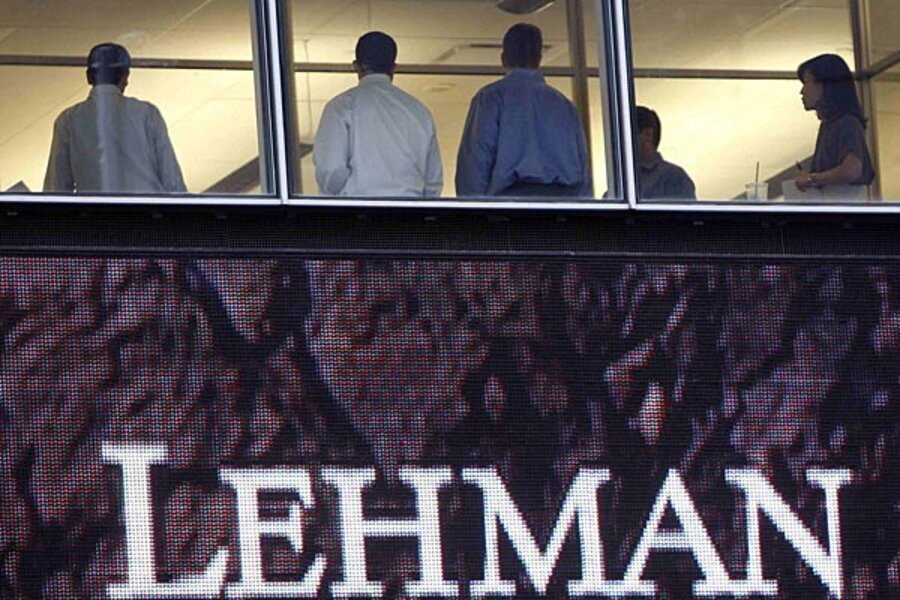

Five years ago this September, Lehman Brothers went bankrupt, and the Street hurtled toward the worst financial crisis in eighty years. Yet the biggest Wall Street banks are far larger now than they were then. And the Dodd-Frank rules designed to stop them from betting with the insured deposits of ordinary savers are still on the drawing boards — courtesy of the banks’ lobbying prowess. The so-called Volcker Rule has yet to see the light of day.

To be sure, the banks’ balance sheets are better than they were five years ago. The banks have raised lots of capital and written off many bad loans. (Their risk-weighted capital ratio is now about 60 percent higher than before the crisis.)

But they’re back to too many of their old habits.

Consider JPMorgan Chase, the largest of the bunch. Last year it lost $6.2 billion by betting on credit default swaps tied to corporate debt — and then lied about it. Evidence shows the bank paid bribes to get certain counties to buy the swaps. The Justice Department is investigating the bank over improper energy trading. That follows the news that the anti-bribery unit of the Security and Exchange Commission is looking into whether JPMorgan hired the children of Chinese officials to help win business. The bank has also allegedly committed fraud in collecting credit card debt, used false and misleading means of foreclosing on mortgages, and misled credit-card customers in seeking to sell them identity-theft products. The list goes on.

JPMorgan’s most recent quarterly report lists its current legal imbroglios in nine pages of small print, and estimates resolving them all may cost as much as $6.8 billion. That’s not much more than a pittance for a company with total assets of $2.4 trillion and shareholder equity of $209 billion.

Which is precisely the point. No company, least of all a giant Wall Street bank, will eschew a chance to make a tidy profit unless the probability of getting caught and prosecuted, multiplied times the amount of any potential penalty, is greater than the expected profits.

Have we learned nothing since September, 2008? Five years ago this month Wall Street almost went under. We bailed it out. Millions of Americans are still suffering the consequences of the Street’s excesses. Yet the Street’s top guns and fat cats are still treating the economy as their own private casino, and raking in even more than before.

The fact is, the giant Wall Street banks are ungovernable — too big to fail, too big to jail, too big to curtail. They should be split up, and their size capped. There’s no need to wait for Congress to do it; the nation’s antitrust laws are adequate to the job. There is ample precedent. In 1911 we split up Standard Oil. In 1982 we split up Ma Bell. The Federal Reserve has authority to do it on its own in any event. (Would Larry Summers take such an initiative?)

Legislation is needed, however, to resurrect the Glass-Steagall Act that once separated commercial banking from casino capitalism. But don’t hold your breath.

Happy fifth anniversary, Wall Street.