Teacher in Uganda: Why give celebrity status to a killer in Kony 2012?

Loading...

| Lira, Uganda

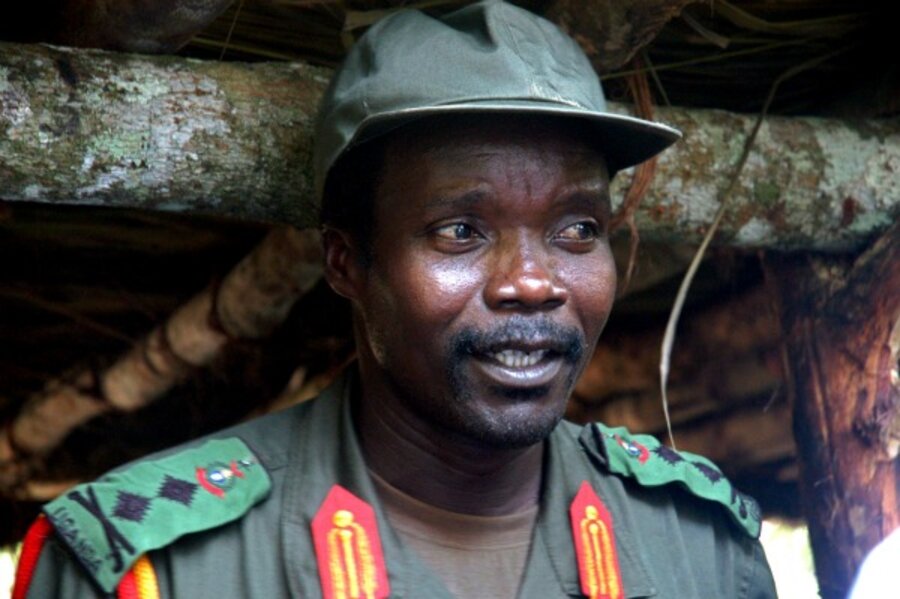

Until last week, I had not seen Joseph Kony’s face in northern Uganda for almost six years. The leader of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) had long since relocated his campaign of violence and fear elsewhere, likely to the Central African Republic.

And yet, suddenly, with the release of the video Kony 2012 on YouTube, Joseph Kony – rapist, terrorist, murderer – is now an international celebrity.

At the high schools where I teach in Lira, in northern Uganda, Mr. Kony left gut-wrenching memories behind – memories of children abducted in the middle of the night, of girls raped, of mangled faces of those who survived and memorials to those who didn’t.

And now those memories are resurfacing, not because of any new atrocities on Kony’s part, but because of an effort by some young Americans at an advocacy group called Invisible Children. They want to focus attention on his past.

The LRA led vicious attacks in northern Uganda for 20 years, killing tens of thousands of people and abducting children as soldiers and slaves. But Kony and his LRA were pushed out of the country by the Ugandan Army, and there have been no LRA attacks here since August 2006. Most of the 1.8 million displaced people have returned and are trying to reconstruct their lives.

I teach and mentor at a leadership and entrepreneurship program at four high schools in Lira, working to rebuild these young people’s self-confidence and ability to chart a better future for themselves and their communities. The students, given an opportunity to develop and learn in peace and security, have been making solid – in some cases tremendous – strides.

Now that progress is threatened by a video on YouTube. Recently, one of the older boys asked me in a low tone, “Madame Angella, could the war come back?” As his teacher and mentor, I felt obliged to assure him. “No, Daniel there is only peace now.”

Even if I am right, Daniel’s question betrays the fear that I am trying hard to help my students overcome. After years of concentrating on his studies, Daniel, like many of his classmates, cannot help but wonder where his efforts will lead.

I must confess to a sense of unease as I watched “Kony 2012.” The video shows children being abducted from their homes in the middle of the night. It portrays a people still mired in a horror put on them by a deranged rebel leader, a group that seemingly remains helpless to build a better future for itself.

It instilled in me a confused mixture of shock and pain. It is an agonizing reminder of a miserable past, but it shows nothing of our progress.

If I can’t explain “Kony 2012” to myself, how can I explain it to my students when they ask of Kony: “You cut off my lips, you cut off my legs, and as punishment you get celebrity status in America?”

Why not make the surviving children famous? Why not highlight those who are working hard to make Uganda better?

Daniel is one of my rock-star students. He dropped out of school for three years to ensure that his mother and siblings got a better life after losing his father during the insurgency. He tried various forms of businesses before returning to school. He wants to be the leader northern Uganda needs to rebuild.

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Daniel had been the star of the YouTube video? “Daniel 2012” would be such an inspiration to us all.

Since Kony’s expulsion six years ago, Ugandans have moved on with their lives. No longer in internally displaced persons camps, they have constructed permanent houses, started businesses, and grown their own food. And there are the schools, Uganda’s great hope for the future.

But now, thanks to Joseph Kony on YouTube, foreigners are again looking at Uganda as a country of misery and torture, making the years of progress and development we have made just an afterthought. We defeated the LRA. But it doesn’t seem to matter, at least not to outsiders.

It does matter to Ugandans, though. And that progress is irreversible if we keep pushing forward, regardless of whether Kony is eventually captured or not. Perhaps that is my message to students such as Daniel. What we are doing matters to us, and to our future.

Angella Bulamu is a Ugandan native and mentor for Educate!, a Uganda and US based non-profit developing young leaders and entrepreneurs in Uganda. She works at four schools in Lira in northern Uganda.