China’s reach for sage advice

Loading...

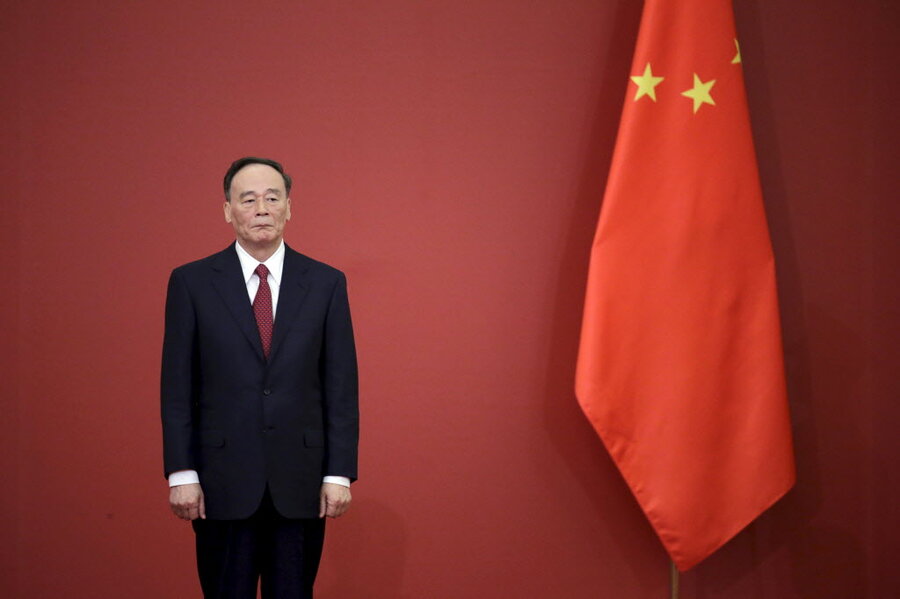

China’s top anti-corruption fighter, Wang Qishan, wrote last week that the Communist Party must learn from traditional Chinese culture to further root out corrupt officials. In other words, the ruling party, whose origins lie in the materialist approach of Marxism, needs the virtues of ancient China to maintain its “basis for governing.”

“Dangers of laziness, inability to properly act, remoteness from the people and passive corruption hang even more acutely in front of the party,” he wrote in the party’s official People’s Daily.

He is not the first top official to warn of the party’s moral decay or even to advise it to adapt ideals from sages like Confucius. But as the official disciplinarian in charge of the party’s anti-corruption campaign, Mr. Wang’s advice might well bring some results.

This week, the party launched its next five-year economic plan at an important meeting of its Central Committee. But the party knows China’s problems are more moral than economic. Since 2013, it has ousted hundreds of cadres for corruption and still finds it must keep tightening party rules.

The latest rule: no playing golf. The sport is seen as too elitist and expensive.

The party is not alone in dealing with moral failures. A 2014 nationwide survey on spiritual life by the East China Normal University found a crisis of trust in society and a high level of moral relativism. More than half of those surveyed agreed that people’s values differ enough that “there should be no good or bad, right or wrong regarding moral issues.”

Someone who has thought deeply about China’s ethical problems is He Huaihong, a philosopher at Peking University. A new book of his writings was published in English this month by the Brookings Institution, titled “Social Ethics in a Changing China: Moral Decay or Ethical Awakening?”

Mr. He sums up the problem this way: “Our material and military power is at an extraordinary peak, but the spiritual and cultural bonds that keep us connected to one another have never been weaker.”

He warns that the party’s attempts at a reconstruction of a moral society must include a recognition of the right of individual conscience. Renewing Chinese culture, he writes, must include a renewal of “spiritual roots.”

“Movements that aim only to acquire greater material wealth will never have spiritual power; simple nationalism will never have the spiritual power to draw in other nations. If every people pursues merely the interests of its own state, then we might have a universal value, but it will be a value of exclusion and conflict,” he writes.

Spiritual beliefs, like the concept of universal love and an equality among all, “pervade every aspect of our lives and represent our ultimate life goals. And they exist on their own plane. They cannot – and should not – be forced, and modern society increasingly accepts that fact.” Such beliefs are “strong and sustained.”

His writings represent a wider debate in Chinese society about how to nurture what he calls the “spiritual undergrowth,” especially the beliefs that help people rise above self-interest. The fact that such a debate exists at all is a sign of hope. And the fact that the party’s top anti-graft official is now reaching back for a bit of ancient wisdom is even a better sign.