Britain’s answer to angry voters

Loading...

Both the American election campaign and Britain’s vote to leave the European Union (“Brexit”) have revealed deep voter concerns about the effects of globalization on jobs and incomes. Trust in big business has eroded, forcing politicians to respond. Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump each promise radical changes on issues such as trade and finance.

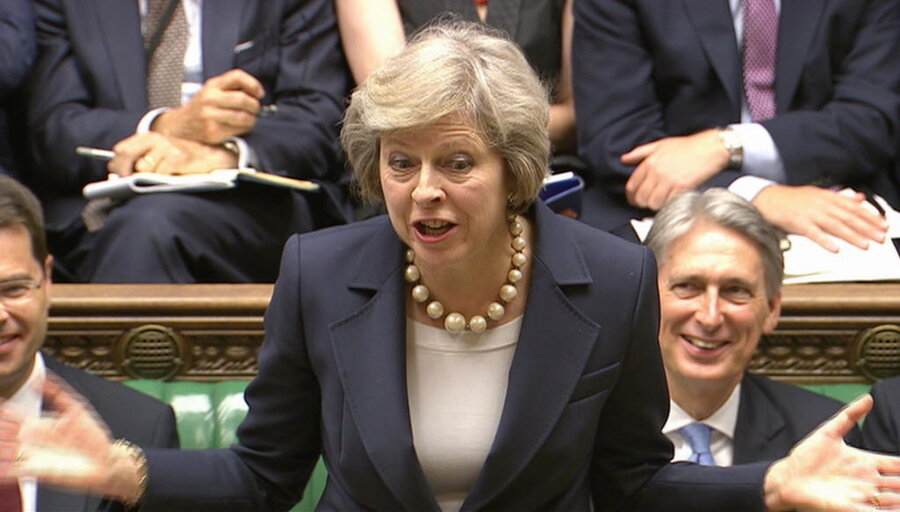

In Britain, however, a new prime minister, Theresa May, has taken office since the Brexit vote in June. She is already acting on worker concerns. Her most radical idea: Put employees on company boards in order to “put people back in control.”

Ms. May does not fit the stereotype of a free-market Conservative. She would like Britain to adopt the idea of “worker directors” – a concept already practiced in countries such as Germany, Sweden, and France – in order to restore trust in the corporation. She views corporations as a society of stakeholders, from employees to consumers to local communities, and not merely as entities beholden to stockholders.

Conservatives, she says, “don’t just believe in markets, but in communities. We don’t just believe in individualism, but in society. We don’t hate the state; we value the role that only the state can play.”

In the United States, such ideas have long been espoused by some conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans. Yet too often they have faltered because of each party’s polarizing plays for power. Under Britain’s parliamentary system, which combines legislative and executive powers, May can more easily implement her ideas.

But will this change in corporate governance bring the kind of sustainable growth and shared profits that she envisions?

On the Continent, the record is mixed when corporate boards include worker representatives, according to a study by Bloomberg News. In Germany, where the practice has existed for decades, more companies are finding ways to avoid the practice. Some European companies do worse in the marketplace when they share strategic governance with workers.

Much of the success in worker directors depends on how they are chosen and how well they are trained. The idea is designed to signal that workers have a stake in “the system.” It can drive a longer-range view of a company’s future and its sustainability.

If May’s idea is done well and those implementing it learn from Europe’s mistakes, she might be able to restore trust in today’s globalized economy. She said the people of Britain voted for “serious change.” Her change would not break up corporations. Rather, it would bring companies and the people they serve back together.