Why walls rise -- and must fall

Loading...

We build walls for many reasons – to proclaim ownership, to provide privacy, to ensure safety. Also out of fear and spite. Walls keep others out and keep us in.

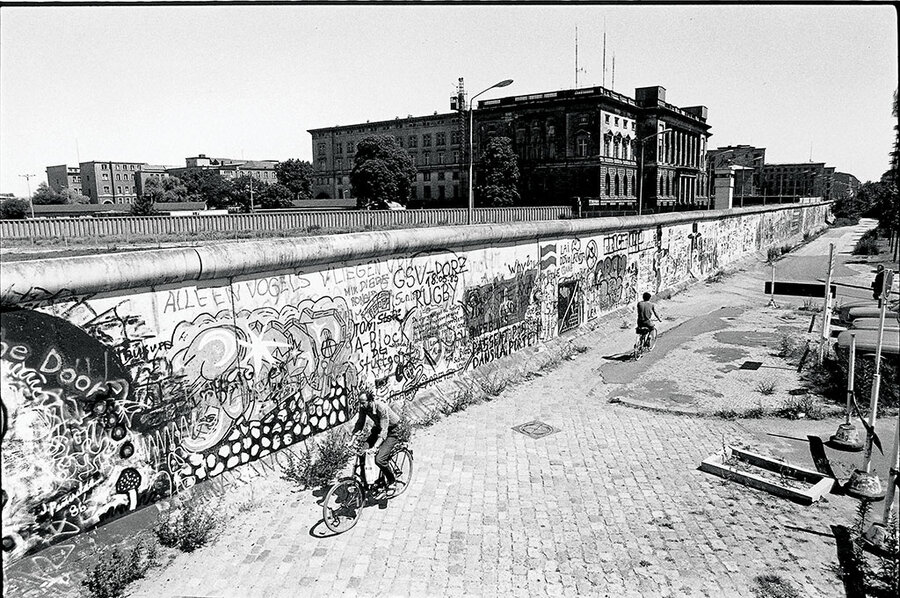

Twenty-five years ago next month, a great wall fell in Berlin. For decades, the Berlin Wall had been the symbol and centerpiece of the Iron Curtain, which stretched from “Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” in Winston Churchill’s famed words. By the late 1980s, the communist system that built that barrier was in tatters. The world-changing Soviet leader of that time, Mikhail Gorbachev, had winked his approval to Eastern European reformers. Hungary had opened its borders to allow East Germans to go west. West German embassies in Prague and other capitals were flooded with eager escapees. Mass demonstrations erupted in Leipzig and East Berlin.

On Nov. 9, 1989, the world gasped in astonishment. We were all Berliners that day, all feeling a collective thrill as easterners and westerners pounded the wall with hammers and crowbars, embraced one another, and celebrated in a days-long rave along the once deadly strip known as no man’s land. The concrete monstrosity tumbled. History’s tectonic plates shifted. The quarter century since that epochal event has seen the birth and growth of a new Europe – with all the achievements, missteps, hopes, and disagreements that freedom always brings.

By contrast, the Near East of 1989 was moving in the other direction. Fear was growing; hope receding. From the late 1960s to the late ’80s, relations between Palestinians and Israelis, while never free from tension, had been relatively relaxed. In the souks and shops and public spaces of the two regions, both peoples mingled, made deals, shared cups of tea. Some struck up friendships. Some fell in love.

That changed as militancy and violence overcame both sides in what became known as the first intifada. Barriers went up, first makeshift then permanent. Common space vanished. As you can see on the map on page 29 that accompanies a Christa Case Bryant cover story (click here), a great wall now stretches from the slopes of Mt. Hermon to the Gulf of Aqaba.

Sometimes separating people is a practical necessity. Greeks and Turks on Cyprus, Serbs and Kosovars in the Balkans, Pakistanis and Indians in the subcontinent – all have such deep differences that, for now, they are better off apart than together. Divorce is no one’s first choice, but it is sometimes the only practical one.

But walls are not permanent solutions. Robert Frost’s best point about them wasn’t that they make good neighbors (they can but not always), nor that they are unloved and often breached. It is that before building a wall it is wise to ask what is being walled in and walled out.

Fortress Israel has walled in Israelis in relative safety. After almost three decades of violence, that is somewhat understandable. But it has walled out the people they will always share that land with. Someday, hope will conquer fear. Someday – not now but eventually – that wall, too, must fall.

John Yemma is the Monitor's editor-at-large. He can be reached at yemma@csmonitor.com.